Why AI Infrastructure Policy — not chips alone — will decide who leads in AI

Input

Modified

U.S. AI leadership now hinges on AI infrastructure policy, not just models or chips Fragmented laws and grid limits quietly slow scale and raise costs National coordination is essential to stay competitive

The real race to lead in AI will be won not by smarter algorithms, but by better infrastructure. Electricity, internet, and clear rules matter most. Even the best AI models need cheap power, fast internet, and supportive laws to thrive and scale. Right now, the United States has a lot of smart people and good cloud computing resources, but it's facing some big problems. The demand for electricity in data centers is rising rapidly. The electricity grid is old and struggling to keep up with the new demand. Plus, the different laws in each state make it slow, expensive, and difficult to expand things across the country. If politicians deal with these problems separately, we will end up with a bunch of small, local solutions that don't really help. What we really need is a national plan for this technology. So, instead of just focusing on who invents the next big AI model, we should be thinking about who can create the right kind of infrastructure policy. This means bringing together energy, grid planning, and federal laws to enable computing power to grow where it's needed most.

AI Infrastructure Policy: A Necessary Change in Strategy

People often frame regulation as a choice between caution and speed, but regulation and infrastructure are linked. Confusing state rules drive businesses to areas with clearer, cheaper processes, shaping where data centers are built and influencing local economics and politics. So, the question isn't just about how strict the laws are, but whether we can create a system that encourages the building of large-scale computing infrastructure while still protecting the public good. The recent efforts by the White House and governors to work together on grid issues show that they understand this connection: electricity and rules are now part of the same strategic plan.

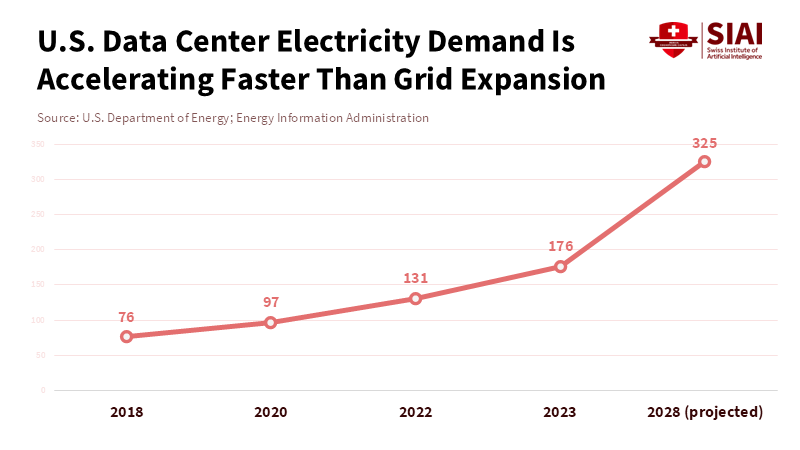

Data centers in the U.S. used about 176 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity in 2023, or roughly 4-4.5% of total U.S. energy consumption. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, renewable energy sources are expected to account for around 10% of total U.S. energy consumption by 2028, with the potential to reach higher shares if current growth trends persist. If the process of obtaining permits, connecting to the grid, and resolving how to share costs across states is not accelerated, companies may encounter significant challenges in certain locations or consider moving their operations to other countries or states that offer more favorable incentives. This is how a confusing mix of laws can put us at a disadvantage: it makes things more expensive and limits the number of places where companies can operate, which allows countries with better policies to get ahead.

Grid Problems, Political Issues, and Where Computing Happens

The electricity system is now a key part of the policy. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) says that electricity demand in the U.S. will reach new records in the mid-2020s, and the pressure will keep increasing through 2027. The Department of Energy also warns that if we shut down too many power plants without quickly replacing them, we could see a significant increase in power outages. These aren't just predictions for the future. They're already affecting what governors and federal leaders are doing.

In January 2026, the White House brought together governors to urge PJM and other grid operators to accelerate the connection of new power sources to the grid, add more capacity, and ensure that big tech companies pay a greater share of the costs of expanding the system. Why? Because data centers aren't just regular customers. They can cause sudden, large increases in demand near where they are built and strain power lines that weren't designed to handle such high consumption.

Technical problems create political issues that shape new regulations. States facing higher electricity bills and price spikes are prompting politicians to increase oversight, halt projects, or demand special payments, thereby fragmenting the national market. Clear national rules or shared cost mechanisms would enable large-scale planning and investment. The previous administration tried to address these issues by requiring data centers to bid for contracts or help expand the grid, aiming to prevent local conflicts. While logical, this is insufficient—without a single federal authority or speedier grid connections, financial strategies still confront state and local legal obstacles. Thus, errors risk either causing scarcity or eroding local responsibility.

Regulation, Competitiveness, and Looking at Other Countries

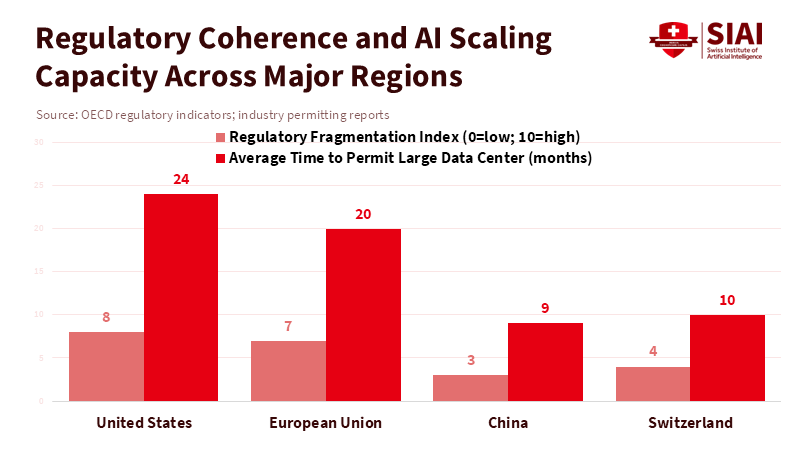

Now, let's talk about the main legal issue. The United States has a mix of federal, state, and agency rules that create uncertainty and overlap in requirements for AI companies. This uncertainty is what officials have called anti-innovation, and they are calling for a single national set of rules to simplify things. Compare that to how things are done in China, where the central government can quickly clear the way for infrastructure and data flow within the country. The point is clear: a unified system can lower the costs of large-scale operations. According to a report from TMTPOST, if Chinese officials continue to provide predictable, centralized approval and China sustains coordinated investments in grid and computing infrastructure, that predictability could help the country lead in building the large-scale systems required by modern AI.

Europe, by contrast, serves as a cautionary example. The EU's AI Act and other digital rules are meant to protect people and set high standards. But they have also led to higher costs and a more cautious approach by companies, slowing the growth of computing-intensive applications. Companies are reporting complex requirements and higher legal costs, and some research and hosting activities are moving to countries with more lenient regulations to save time and money. Switzerland shows a different approach. Its strong research institutions, targeted investments, and business-friendly data environment have made it an attractive place for certain types of research and operations. However, Switzerland doesn't have the scale that the U.S. needs. It simply shows the value of predictable, pro-innovation systems with minimal regulation. The lesson for U.S. policy is not to copy any one country, but to design a system that protects the public interest while avoiding harmful fragmentation.

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Need to Do

First, educators and institutions should: plan for distributed computing environments, partner with cloud providers or regional groups to secure reliable power contracts, rethink campus IT strategies, including flexible purchasing and negotiating for colocated microgrids, design courses connecting energy policy to AI development, treat computing infrastructure as part of campus capital planning, train data science students in energy constraints and include legal compliance content in tech policy courses. These steps will prepare graduates for a fragmented regulatory landscape.

Policymakers should focus on three clear actions. First, create federal data governance and safety standards to reduce differences across states. Second, establish faster and prioritized pathways to connect critical computing projects to the electricity grid, backed by enforceable expansion plans. Third, develop cost-sharing arrangements for new power infrastructure that do not raise prices for local residents. While these steps need not remove state authority, they must eliminate regional bottlenecks. Recent White House moves to engage grid operators are positive, but they require firm legal backing to give companies consistent rules across the country.

Third, be prepared for common criticisms. Privacy and safety advocates will be concerned about giving the industry too much freedom. The response is simple: ensuring that things are connected doesn't mean being lenient. A federal framework can ensure strong protections while removing unnecessary bureaucracy. Similarly, environmental critics will point to rising electricity usage. The correct response is to connect computing growth to investments in clean energy and to set efficiency standards for hardware and software. Finally, some will say that national coordination is unrealistic. That's a practical issue, not a reason to avoid action. It just means we need to develop a better strategy: build strong coalitions around shared economic benefits (manufacturing, jobs, and exports) and use federal funding to reduce political friction between states. Evidence shows that private investments flow more predictably when there is a federal guideline.

Implementation Paths and Specific Steps

Implementing an AI infrastructure policy requires detailed work. Congress can set guidelines that preserve the roles of states while creating a single set of compliance rules for key issues like model safety standards, cross-border data transfer rules, and a federal permit process for data centers that meet energy efficiency and local benefit requirements. The Department of Energy and FERC should issue grid connection standards with clear timelines and penalties for inaction, and the federal government should offer matching funds for transmission in regions that accept new large-scale computing facilities. On the financial side, it requires long-term contracts and use-it-or-share-it rules so that data center developers invest in reliable power generation capacity rather than relying on short-term market purchases. In short, combine regulation with incentives and consequences so that market participants can plan with confidence.

For the education sector, the implementation steps are simpler but urgent. Create public-private regional groups that combine demand from universities, hospitals, and small businesses to create shared computing zones with negotiated power arrangements and community benefits. Encourage grant programs that fund joint investments in microgrids and cooling innovations. And require that federal research funding for AI projects include plans to reduce energy impact, transparency on computing footprints, and partnerships that build regional technical capacity. These steps protect communities while allowing the academic and nonprofit sectors to remain competitive.

We started by acknowledging a hard truth: AI models don't win races on their own; systems do. The United States still has talent, money, and top-notch research institutions, but those resources won't turn into lasting leadership if power grids are strained, permit processes are delayed, and a patchwork of state laws makes nationwide growth impossible. AI infrastructure policy needs to be treated as a strategic policy, not just an addition to technology law. That means combining federal authority on safety and data with concrete investments and rules that allow computing to grow where it benefits the public and the economy. Educators and institutions can prepare by reorganizing purchasing and training, and policymakers can act by aligning rules and financing to reduce friction. If we adopt a clear framework now, we can maintain both our ethical commitments and our competitiveness. If we don't, the advantage will go to those who figured out how to be aligned first. The choice is structural, and time is running out.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. “White House and governors pressure grid operator to boost power supply, slow electricity price hikes.” AP News, 16 Jan. 2026.

Congressional Research Service. “Data Centers and Their Energy Consumption.” CRS Report R48646, 26 Aug. 2025.

Department of Energy. “DOE Releases New Report Evaluating Increase in Electricity Demand from Data Centers.” U.S. DOE, 20 Dec. 2024.

Energy Information Administration. “Short-Term Energy Outlook.” EIA, 13 Jan. 2026.

KPMG. “Decoding the EU AI Act.” KPMG Insights, Mar. 2024.

Reuters. “Governors head to White House on Friday to unveil deal to curb power prices, sources say.” Reuters, 15 Jan. 2026.

Scientific American. “Kratsios Calls Patchwork State AI Laws ‘Anti-Innovation’ at House Science AI Hearing.” Scientific American, Jan. 2026.

Swiss practice guides / Chambers. “Artificial Intelligence 2025 — Switzerland.” Chambers Practice Guides, 22 May 2025.

Comment