When Reciprocity Fails: Why Reciprocal Tariffs Are Mostly Economic Self-Harm

Input

Modified

Reciprocal tariffs raise costs at home, shrink global trade, and rarely deliver lasting protection When two countries retaliate, third-party exporters often gain while consumers and firms lose Measuring the true cost of protection shows tariffs and counter-tariffs are equally damaging policies

Reciprocal tariffs are being sold as a blunt instrument to rebalance trade. In fact, they tend to do the opposite. When two large economies slap matching duties on each other’s imports, GDP falls, prices rise, and the largest share of benefit flows—not to the protected producers—but to third-party suppliers and to rent-seekers at home. The data are stark. Recent projections show that the reintroduction or wide use of reciprocal tariffs can shave tenths of a percentage point off global trade growth in a single year and, in stressed scenarios, reduce global output by far more. The phrase “reciprocal tariffs” should therefore read as a warning label: in most realistic settings, they shrink markets, shift supply chains, and redistribute income in ways that harm consumers, workers, and the public budgets that rely on healthy growth. This column reframes the debate: instead of asking whether reciprocal tariffs are deserved or politically expedient, we should ask how policymakers can avoid the predictable economic damage they create and instead use targeted tools that protect legitimate adjustment needs without wrecking the broader trading system.

Why reciprocal tariffs harm growth

Reciprocal tariffs do their damage in three interconnected ways: they raise costs for domestic consumers and firms, distort comparative advantage and investment decisions, and heighten policy uncertainty. The first effect is immediate and mechanical. A unilateral tariff raises the price of imported inputs and consumer goods; when the partner responds with matching duties, the resulting price shock is amplified across bilateral supply chains. Firms that rely on imported intermediates face higher production costs and either absorb smaller margins or pass costs to customers. Consumers see lower real incomes, and services that depend on tradable inputs are squeezed. Empirical evidence from the 2018–19 US-China measures shows this pattern: tariff hikes then were largely absorbed by buyers, not foreign suppliers, and by the end of 2018, reduced US real income by an estimated amount that accumulated rapidly. These income losses matter for schools and public services because slower growth narrows tax bases and limits the fiscal space that governments use to fund education and retraining.

Reciprocal tariffs also warp investment signals. Firms decide where to locate production based on expected costs and market size. Suddenly, broad-based tariffs make those expectations volatile. Instead of investing in productivity improvements, firms either delay capital spending or redirect investment toward tariff-shielded production that is less efficient. The macro literature finds persistent output and productivity losses after tariff hikes: undoing recent major protectionist measures could raise output by several percentage points over a few years, which is a reminder that the long-run cost of tariff shocks is not trivial and that protectionism’s short-term shield often becomes a long-term drag. Finally, reciprocal tariffs raise policy uncertainty, which, in turn, lowers trade and investment. The World Trade Organization’s adjusted outlook for 2025 shows that when reciprocal tariffs are introduced or threatened, world merchandise trade growth can be cut by multiple tenths of a percentage point in a single year; those lost trading opportunities disproportionately undermine demand for education-intensive services and reduce the payoff for public and private investments in skills that rely on stable global markets.

Trade diversion, third-party gains, and the True Cost of Protection

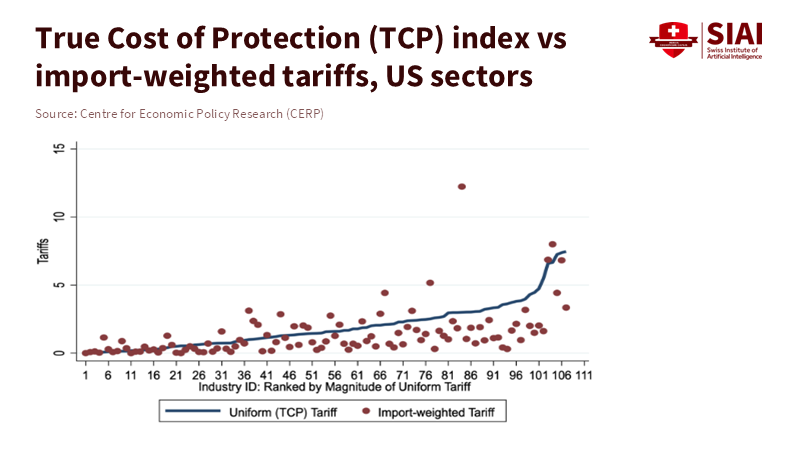

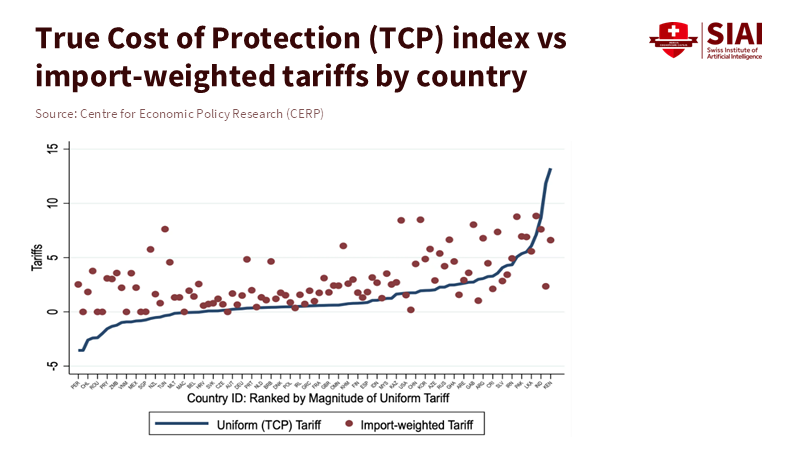

A key reason reciprocal tariffs are often misinterpreted is that they redistribute, not eliminate, trade. When two countries raise mutual barriers, their direct trade falls. But that decline does not disappear into nowhere: trade is diverted. Third-party suppliers—competitors in other regions—tend to capture the freed export shares. That can look like a short-term “win” for some developing exporters, but it is a fragile one. Empirical analysis of past tariff episodes, including the US-China dispute, shows mixed short-run evidence for large-scale diversion: some product groups reallocate quickly to third markets, while many complex intermediate goods retain supply ties to the original producers, at least initially. A systemic escalation of reciprocal tariffs, however, magnifies these effects and creates chains of reallocation that are costly to unwind. The True Cost of Protection idea reframes measurement by accounting for these ripple effects. Rather than measuring tariffs only by the direct import weight on which they are imposed, the True Cost approach weights tariffs by how trade shares shift between buyers and among competing suppliers. This reveals that a tariff’s “true” burden is often higher than conventional import-weighted indexes show, because they miss the indirect costs imposed through trade diversion and global supply-chain interdependence.

That reweighting matters for policy because it changes who bears the cost. Domestic headline figures—imports from the targeted partner—fall, giving the political impression of success. But consumers pay higher prices, firms face squeezed margins, and third-party exporters expand into those bilateral gaps. According to a 2024 IMF analysis, when the United States imposed tariffs on China in 2018–19, Vietnamese firms saw new export opportunities to the US, leading to job creation, especially among firms facing higher tariffs. However, while some countries can benefit from such shifts, other research and trade outlook simulations indicate that broad, reciprocal tariffs tend to reduce global trade volumes and overall economic output. The True Cost lens reveals the distributional details: tariff protection can appear effective on one bilateral ledger while being socially costly on the global ledger. For educators and universities that teach trade policy or manage international research partnerships, this means the narrative must include spillovers and second-order effects—not just the binary “we impose tariffs / they lose market share” storyline. According to research by D. Bown and M. Crowley, conventional economic measures often fail to capture the full losses from trade policy uncertainty, underscoring that reciprocal tariffs are ineffective tools for achieving long-term national prosperity.

Concrete implications for educators, administrators, and policymakers

Education leaders, university administrators, and policymakers should recognize that policy debates around reciprocal tariffs require a thorough understanding of their broader economic impacts, as highlighted by recent studies on trade policy uncertainty. First, they must prioritize transparency in cost estimation and scenario planning. School systems, vocational trainers, and universities depend on predictable labor markets to plan capacity. When tariffs raise uncertainty, enrollment in programs aligned with tradable sectors can fluctuate wildly. Administrators should therefore develop short-run contingency plans that preserve core teaching capacity while offering flexible up-skilling modules aimed at sectors likely to face reallocation pressures. For example, if tariffs raise the cost of imported electronics, retraining programs can focus on local value-chain upgrades—assembly, quality control, and services for electronics—while explicitly tracking whether these roles are temporary or likely to remain. Policymakers must use evidence from trade-adjustment studies to calibrate support: the 2018–19 tariff episode produced measurable monthly income losses and regionally concentrated employment shifts, but it also created export opportunities elsewhere. According to a report from the National Bureau of Economic Research, recent increases in U.S. tariffs highlight the importance of designing compensation and retraining programs that are tailored to specific regions and time frames, rather than providing blanket subsidies that could support inefficient producers.

Additionally, policymakers should require thorough and transparent cost assessments before implementing reciprocal tariff measures. Macro estimates now show that broad tariff episodes can materially reduce global trade growth in a single year and lower output cumulatively over multi-year windows; the scale depends on how widespread the measures are and how long uncertainty persists. Where tariffs are mooted to protect strategic industries, policymakers should weigh alternative instruments—targeted R&D tax credits, time-limited wage subsidies for displaced workers, and public investments in infrastructure and schooling—that protect long-term competitiveness without triggering retaliatory cascades. For education policy, the lesson is clear: invest in portable skills and in regional centers that can pivot as firms reconfigure supply chains. Curricula should emphasize digital literacy, trade logistics, and the management of complex supply networks—skills that retain value even if production footprints shift across borders. Finally, governments should be careful with rhetoric. Political leaders often present reciprocal tariffs as simple retribution. The economic record shows the costs are diffuse and persistent; honest public communication helps maintain trust and allows educators to plan with clearer expectations.

Reframing the choice

Reciprocal tariffs look decisive. They promise quick action and draw headlines. The evidence says they are mostly a form of economic self-harm. They raise consumer costs, distort investment, and spread damaging uncertainty. They also redistribute trade in ways that temporarily advantage some third parties but leave the world poorer on net. The True Cost perspective matters because it forces us to account for the full set of ripples a tariff sends through trade networks. For educators and policymakers, the policy takeaway is pragmatic: do not let short-term political theater substitute for careful, evidence-based adjustment policy. Invest in skills that travel, design targeted transition assistance, and use fiscal tools that raise productivity rather than shelter inefficiency. If the political appetite for tariffs remains, constrain it with transparent costing, sunset clauses, and independent reviews that measure the True Cost. Only then can we protect legitimate domestic concerns without sacrificing the broader prosperity that funds our schools, universities, and public institutions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The impact of the 2018 tariffs on prices and welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210.

Anderson, J. E., & Yotov, Y. (2025). Tariff reciprocity and the True Cost of Protection Index. CEPR / VoxEU.

Boer, L., & Rieth, M. (2024). The Macroeconomic Consequences of Import Tariffs and Trade Policy Uncertainty (IMF Working Paper No. 2024/013). International Monetary Fund.

BNP Paribas Economic Research. (2025). “Reciprocal” tariffs are bad for world growth and worse for the US. EcoWeek, 25.14 (April 7, 2025).

European Central Bank. (2020). The impact of US tariffs against China on US imports: evidence for trade diversion? (ECB Working Paper No. 2503).

Fajgelbaum, P., Goldberg, P. K., Khandelwal, A., & Kennedy, P. (2021). The Economic Impacts of the US-China Trade War (NBER Working Paper).

International Monetary Fund. (2024). The Macroeconomic Consequences of Import Tariffs and Trade Policy Uncertainty (Working Paper).

Rotunno, L., Roy, S., Sakakibara, A., & Vézina, P.-L. (2024). Trade policy and jobs in Vietnam: The unintended consequences of US-China trade tensions (IMF Working Paper).

World Trade Organization. (2025). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics (April 2025).

Comment