The Weak Dollar and the End of Safe-Asset Privilege

Input

Modified

The weak dollar reflects a loss of trust in U.S. financial stability Political risk is now priced directly into U.S. assets and Treasuries Global education and funding systems must plan for permanent currency uncertainty

In 2024, the U.S. dollar accounted for 57.8% of the world's official reserve funds. This number should prompt people to reflect. A weak dollar isn't just a minor thing that affects only specific markets. It distorts the actual value of scholarships and grants from other countries. According to a report from the IMF, exchange-rate movements have significantly affected the value of the US dollar relative to other currencies, which means that when schools receive tuition payments in foreign currencies, the funds may translate into less money if the dollar appreciates. Additionally, schools and research programs in countries with weaker currencies have greater difficulty repaying dollar-denominated debts. Any college, university, foundation, or program that does work around the world needs to rethink its plans because of the weak dollar. They need to make some fundamental changes, such as planning for different scenarios, having clear rules about what's covered, including price-link clauses in contracts, and talking openly with the people who donate and make decisions. It's no longer advisable for those who support and run global education to view the weak dollar as merely a distant market problem.

How the weak dollar is changing things around the world

The dollar’s important position comes from three simple facts: many people hold it as a reserve currency, use it to set prices for international trade, and trust it as a safe place to go during crises. This mix gave the U.S. an advantage in how it got money. For many years, the country could run deficits without much immediate harm. However, this advantage has recently been tested. Those who manage reserves and buyers respond more quickly when policies appear uncertain. They don't just look at the numbers; they also wonder if the promises about money will last. This means the safety net, once seen as untouched by politics, is no longer as solid. Policy decisions can now affect the cost of obtaining funds more quickly than they did 10 years ago. (Note: The things used to measure this are the IMF's COFER reserve numbers, the U.S. Treasury's TIC data on who owns what based on where they live, and the BEA's annual trade numbers. End-of-year numbers were used instead of monthly ones to keep things clearer.) For governments, the message is clear: having clear, stable plans lowers the speed at which markets adjust the price of risk.

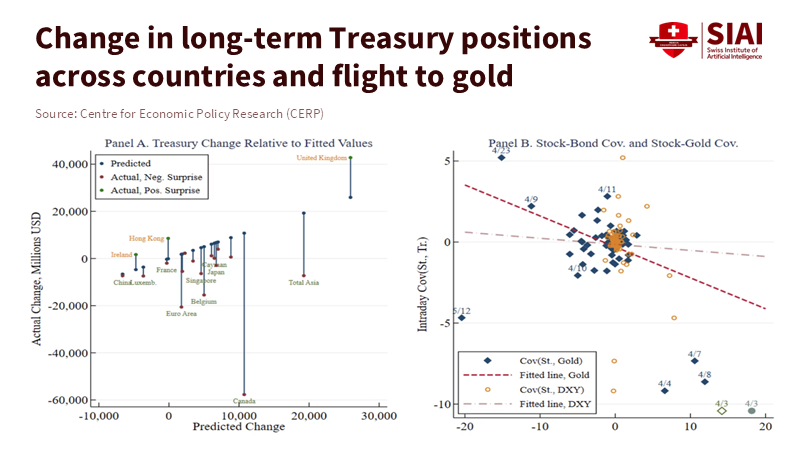

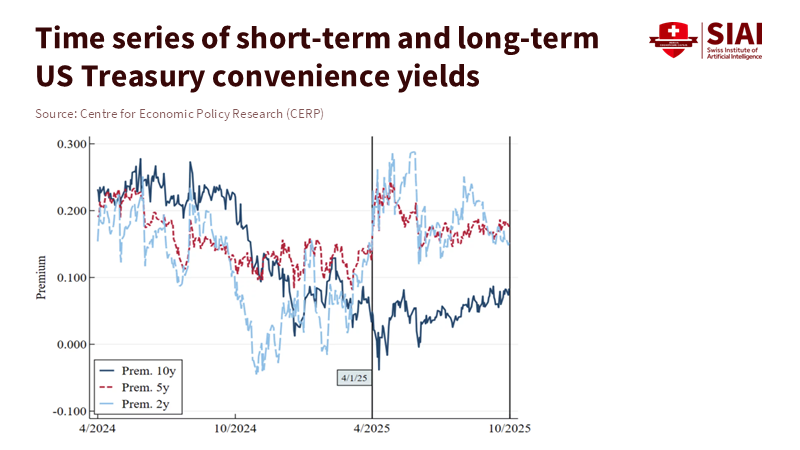

The numbers for reserves and trade show this change in a real way. Foreign countries held about $8.2 trillion in U.S. bonds in 2024. That's substantial, but it obscures how and where holders are making changes. At the same time, the U.S. deficit in goods and services went up by about $133.5 billion in 2024 — about a 17% increase from 2023. These numbers indicate that the U.S. requires sustained capital inflows from other countries to address fundamental gaps. When politics makes people uncertain about future monetary outcomes, markets adjust the price of money. This manifests as higher premiums, larger differences in rates for longer-term bonds, or periods when some state buyers step back and shift where they allocate their money. For schools that rely on dollars or borrow in dollars, the change is noticeable: having backup plans is now essential, not merely desirable.

How politics and deficits make the weak dollar show problems

Politics now causes markets to adjust prices more rapidly than in calmer times. Surprises about tariffs, sudden talk about trade, or playing games with monetary policy make buyers reconsider their beliefs about future deficits and how debts will be repaid. When these beliefs change, so do the prices of currencies and bonds. This isn't just a theory. Buyers consider the risk that assurances may be altered for political reasons, and they seek compensation for that risk. The result is that the same debt can cost more if the risk associated with policies increases. For countries and schools that rely on foreign money, the higher cost directly hurts budgets and plans. Models that assume currency rates will remain unchanged don't account for a new risk: sudden policy modifications that shift markets' expectations almost overnight. Political events have uneven effects. A surprise tariff can alter trade and buyer sentiment within a few days. Worries about paying debts evolve slowly but can become serious if markets start to doubt the way things are being done. This mix means that past methods of measuring how unstable things are don't capture the full risk today. Schools need to test different scenarios linked to possible policy paths to be ready.

Raising taxes and cutting costs are quick ways to fix significant gaps in other countries. The big jump in the trade deficit in 2024 shows how big the problem is: trying to fix it with heavy taxes would slow down demand and risk jobs. Real fixes take time and a mix of actions that make the country more competitive and change demand. According to the International Monetary Fund, fluctuations in the U.S. dollar exchange rate can negatively affect organizations by reducing productivity growth, which for schools may result in higher operational costs and pressures to limit hiring, reduce research budgets, or raise fees for international students. According to UNICEF, a decline of US$3.2 billion in education funding by 2026 could put millions of children’s futures at risk, underscoring the need for early planning and collaborative policymaking to safeguard education budgets.

Markets change their minds fast. According to a U.S. Treasury report, despite periods of increased volatility and record trading volumes in 2024–25, trading conditions in the Treasury cash market and financing conditions in the repo market remained orderly. When buyers perceive politics as a signal that guarantees money may change, they reconsider the price of safety. The result is larger rate changes and the loss of the idea that U.S. bonds automatically address global problems at no cost. This removes a form of insurance that had previously kept global borrowing costs lower.

The proof is in both trading data and public talks. According to an IMF Data Brief, the share of US dollar holdings in allocated foreign exchange reserves declined to 56.32 percent from 57.79 percent in the first quarter of 2025, as the value of other reserve currencies rose against the dollar. This doesn't mean U.S. bonds are useless. In significant international panics, dollar money can still attract demand. However, the pattern indicates that U.S. debt no longer provides free protection against all types of risk, especially those arising from policy decisions. Decision-makers and finance teams need to ask different questions now: How much risk do we face from tuition if the dollar moves significantly? According to a Time report, understanding how significant financial changes might affect our fund spending and ability to service bonds should be a central concern in budget discussions, not merely an afterthought.

What This Means for Educators

The solution to this is simple and straightforward. First, make planning for different scenarios standard. Plan for at least three scenarios: a typical situation in which the dollar remains stable, a long-term weak-dollar scenario with larger changes, and a sudden shock driven by rapid price moves following policy announcements. Give everyone a chance of happening and map out how it would affect tuition, fund returns, and costs. Second, think of protection (hedging) as insurance. It costs money when things are calm, but saves programs during shocks. Clearly explain to the people who make decisions, donate, and work there the pros and cons, so they see protection as a good thing, not just gambling. Plans should account for sudden declines in international student enrollment, delayed payments from foreign partners, and sudden spikes in import prices for scientific equipment and books. Financial officers should conduct these tests at least annually and provide a brief summary for decision-makers.

Contracts also need to change. Long-term deals with sellers priced in dollars should include price-link clauses, short timelines for currency-related changes, or cost-sharing mechanisms that allow short-term adjustments rather than canceling the deal. Fund spending rules should be tested at higher rates and import costs for key items. At the policy level, governments should accept that trust in reserve currencies is partly a public good. Transparent budget plans, steady trade policies, and tools to share reserves reduce the chance of sudden price changes and make money more reliable for schools. Governments might also consider temporary financial options or programs that help small colleges handle sharp moves without creating bad incentives.

The weak dollar, accounting for 57.8% of official reserves, is more than a number. It tells us that the trust that once kept global borrowing costs low is now weaker. For the education world, the message is easy. Make plans that assume currency risk is real. Use protection wisely and budget for it. Write contracts with price-link and risk-sharing parts. Ask how political news can turn into money gaps, and test those situations now. Governments need to reduce the frequency of surprise policy shocks and maintain transparent budget plans so markets have fewer reasons to change prices suddenly. This is not about stopping global interaction. It is about being real: Be ready, protect yourself, and keep the global learning mission going even if the dollar gets weaker. The work is technical, but the goal is moral — steady money protects access to research and education in a connected world.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

IMF. 2025. Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER). International Monetary Fund data brief.

Morgan Stanley. 2025. Devaluation of the U.S. Dollar 2025. Morgan Stanley Insights.

Nordea. 2025. Are US Treasuries no longer 'safe haven'? Nordea Markets commentary.

SCMP. 2025. In the age of Trump, are 'safe-haven' US assets not so safe any more? South China Morning Post.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2025. U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, December and Annual 2024. BEA release.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2024. Foreign Portfolio Holdings of U.S. Securities (TIC). Treasury International Capital data.

Comment