The Next Binding Frame: Rebuilding Order When the Rules-Based Order Frays

Input

Modified

The rules-based order is breaking into competing systems Asia is building regional frameworks to manage the shift Education and institutions must adapt to fragmented governance

The international system we've relied on for decades isn't as stable as it used to be. It's like the foundation of a house that's starting to crack. For about eighty years, we had a deal: countries followed certain rules and worked together, and a major power helped keep things in order. This prevented big wars and made it easier to trade and cooperate across borders. Now, that major power seems less willing to keep backing the deal, and some countries are questioning the rules themselves. They never really agreed with the whole idea in the first place.

This change is a big deal for schools and universities because they depend on a shared understanding of how things should work. This understanding supports things like open learning programs, international research, and the exchange of ideas. If the future involves different regions making their own deals and competing with each other, it will be tougher for educators to work together, secure program approvals, and protect academic freedom. Public policy needs to see education as essential for either holding things together or letting them fall apart.

The future of the rules-based order: why the rupture is real and immediate

The way things used to work wasn't perfect. It was a mix of laws, open markets, and security provided by a strong country. This made it worthwhile for many countries to be part of international groups. But, recently, two things have happened that have weakened this shared agreement. First, democracy isn't doing as well as it used to. Many countries have seen a decline in political rights and personal freedoms. It's not just a small issue; more countries got worse in 2024 than improved. Most of the world's population now lives in countries that are only partly free or not free. This makes it harder for international groups and scholars to connect and share ideas. It means we can't just assume everyone agrees on basic principles anymore. We have to negotiate or sometimes even avoid certain topics.

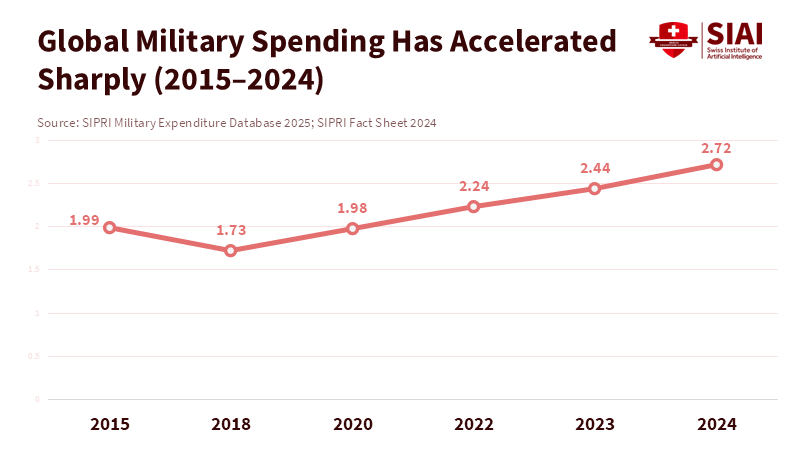

Second, countries are competing more aggressively. Military spending and conflicts are on the rise because of disagreements over territory and the strategies of big powers. The global military budget jumped in 2024, the biggest increase in years. This shows that countries are focusing on military strength and protecting themselves instead of following rules and working together. As a result, countries are trying to protect themselves by making deals with specific partners, securing their supply chains, and strengthening regional agreements instead of relying on international rules. For many countries, this means changing their diplomatic plans, research funding, and the stability needed for international education partnerships.

These problems are made worse by changes in U.S. policy. When a major power starts to pull back or act only in its own interest, other countries react quickly. Alliances can still exist, but they become more complicated. According to the International Monetary Fund, these agreements do not guarantee the same long-term benefits for every participant. Instead of an immediate breakdown, the IMF notes there is a steady reallocation of trust and resources toward more regional and specific agreements. According to UNESCO, education officials from 27 countries recently committed to strengthening cooperation on the fair recognition of qualifications across borders and addressing challenges like educational fraud and the ethical use of artificial intelligence, highlighting the need for more coordinated and forward-thinking plans in education policy.

Regional resilience and the promise—and perils—of plurilateralism

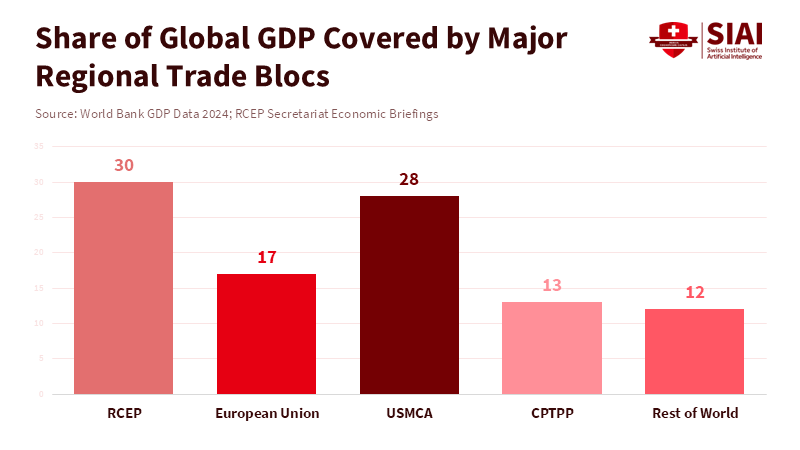

Looking at Asia can teach us something. When faced with global fragmentation, countries in East and Southeast Asia have focused on regional solutions. They try to stay open while protecting themselves from the risks of big-power competition. Agreements like the Region Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and ASEAN frameworks now support a large amount of trade and production in the Indo-Pacific area. These agreements aren't exactly like the old international system. They're practical, often technical, and focused on keeping the economy going rather than changing political systems. This creates opportunities for universities and training centers to keep running international programs. Trade in services, student exchanges, and research collaborations can continue because of these agreements. But, it can also mean accepting cooperation with countries that don't share the same values, unless safeguards are built into the deals.

Regional cooperation can buy time and create space, but it also changes the rules. Instead of one set of global rules, we're likely to see different rules for different issues and regions. This creates both opportunities and risks for educators. According to UNESCO, regional cooperation in higher education offers the opportunity for faster growth of research groups and online learning platforms, but there is also a risk that standards and academic freedoms may vary between regions. According to a report on medical education reform in Asia, efforts to modernize medical curricula are occurring worldwide, including across Asia where regional cooperation is increasingly important. As education leaders navigate these reforms, they may need to balance building connections within their regions and safeguarding their institutions, especially as commercial priorities may affect how much public involvement or debate is permitted compared to programs shaped by older Western models.

At the same time, these regional frameworks can be designed to encourage open research and exchange. Policymakers need to understand that economic openness doesn't automatically create open societies. If education leaders want the benefits of openness—such as peer review, transparent funding, and academic exchange—they need to explicitly include them in regional agreements. According to the International Monetary Fund, managing public investment across regions requires careful coordination to ensure that planning, allocation, and implementation systems are compatible and effective. According to the International Monetary Fund, without deliberate efforts to balance priorities, regional cooperation may be assessed primarily through the lens of economic growth, such as the projected slowdown to 3.9 percent in Asia this year, while important social and civic components of education could be overlooked.

What educators, administrators and policymakers must do now

What steps should educators, administrators, and policymakers take in response? The immediate need is to adapt strategically. Education systems should be seen as essential for national stability and as tools for diplomacy. First, educators and government agencies should include knowledge of international affairs and diverse government systems in teacher and administrator training programs. This isn't about pushing a political viewpoint, but about helping people understand how to run institutions under different rules, protect data and intellectual property, and encourage civic values even in restrictive environments. Second, university groups need to build diverse partnerships so that a single political issue doesn't undermine international collaborations. Having multiple smaller agreements across regions reduces the risk that comes with large, single agreements. These are practical steps that can be planned and measured.

According to a recent World Bank report, concerns have been raised that using education for strategic purposes could undermine academic freedom, highlighting the importance of safeguarding independent learning in such policy decisions. The solution isn't to avoid planning, but to ensure that every effort to strengthen education is underpinned by independent safeguards: transparent funding, protection for scholars, and independent accreditation that keeps education separate from political pressure. Policymakers need to commit to these safeguards through legislation and the guidelines of funding agencies. According to a World Bank report, major international organizations are urging countries to increase investment in education to achieve inclusive and equitable learning, highlighting the importance of support that prioritizes educational goals rather than tying cooperation to political agendas. This approach can help safeguard academic independence. Evidence shows that technical cooperation can work with strong academic standards, but only if those standards are included in the plan.

Finally, administrators should see international student and staff mobility as a security and continuity issue. This means creating flexible visa arrangements, online learning options, and emergency scholarships that allow people to continue their studies or work when borders close. It also means investing in legal advice, international research insurance, and data storage that enables research data to be copied across different locations. These steps might seem routine and expensive, but they're cheaper than letting partnerships fall apart when political relationships sour.

In conclusion, if the future involves a complex and contested international system, we need to start treating education as essential infrastructure, not just something that's affected by events. The old system gave us decades of stability, and its decline doesn't mean we should panic. But it does require us to act intentionally. Policymakers should fund regional tools that protect international scholarly exchange. University leaders should create diverse networks and protect academic freedom. Educators should teach people how to navigate different political environments without giving up their core values. These changes aren't easy, and they require political will and financial commitment. But, in a world where alliances change and institutions are reshaped, a strong education system is the best way to preserve the values of openness that we still cherish. We need to act now to protect the partnerships that will allow learning to continue, no matter what happens politically.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2024). The Rules-Based Order vs. the Defense of Democracy. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

East Asia Forum Editorial Board. (2026). Asia’s response to the rupture of the rules-based global order. East Asia Forum.

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2024). Democracy Index 2023: Age of Conflict. Economist Intelligence Unit.

International Monetary Fund / World Economic Outlook. (2025). World Economic Outlook updates and data. IMF Publications.

RCEP Secretariat / APEC analyses. (2024). Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership: coverage and economic significance. RCEP/APEC technical briefings.

SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). (2025). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024. SIPRI Fact Sheet.

World Bank. (2024). World Development Indicators: GDP and related data. World Bank Publications.

Comment