Invisible Value: Why AI intangible assets Make the Economy Look Smaller Than It IsZ

Published

Modified

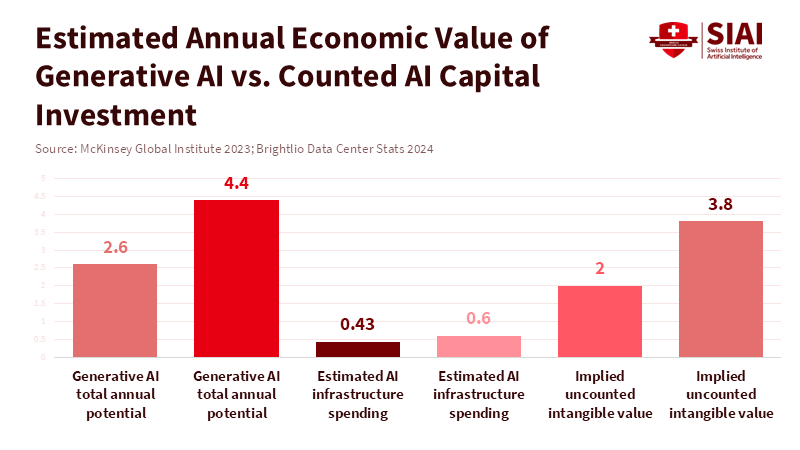

AI capital is being miscounted, shrinking the economy on paper Hidden AI assets distort policy, funding, and skills planning Fixing measurement is now a growth and governance priority

Currently, most official economic reports treat the money companies spend on building AI models, gathering data, and integrating AI into their workflows as regular expenses rather than investments that will create value later. This is a problem because these investments are valuable.

Some studies suggest that AI could add trillions of dollars to the global economy each year. If policymakers and educators rely on economic data that does not accurately reflect these investments, they will misallocate resources for training, infrastructure, and education. This could lead to underfunded training programs, poorly planned public investments, and education systems that do not prepare people for jobs that require AI skills. Accurately measuring what we are building with AI will help us direct resources to the right places. If we continue to ignore AI's strengths, the public sector will focus on minor, obvious things rather than the fundamental drivers of economic growth.

Why Traditional Accounting Misses AI's Value

Intangible assets are now essential to how companies create value. Companies are buying AI models and cloud computing time. Also, they are paying engineers to develop prompt libraries and rating systems. They are also creating ways for AI to function smoothly within their businesses. Much of this spending is recorded as current expenses under standard accounting practices. This makes it appear that these expenses reduce current profits without increasing the company's value. This accounting method affects decisions about treasury forecasts, education budgets, and public investments. Because the way we measure things changes slowly, an economy that is shifting toward scalable digital services that cost little to expand will seem weaker than it is on paper.

Three reasons exist why this miscounting continues. First, many AI-related expenses are diverse and change quickly, making them difficult to categorize neatly. Second, it is hard to measure the true cost because the prices of software-like services do not keep pace with technological changes. Therefore, improvements are hidden and hard to find in economic data. Third, many of AI's products are not sold directly or are bundled with other products. It shows up as increased benefits to consumers or as advantages that spread across companies, rather than as clear payments. Together, these things create an invisible capital problem. Fixing this issue is not just a matter of accounting. It changes which skills schools focus on, how administrators allocate funds for labs and cloud resources, and how regulators design incentives for public infrastructure such as power and data centers.

Measuring the Invisible with Evidence and Estimates

Recent research and reports show that AI's value is visible enough to take action. Studies that include broader categories of intangible assets (such as research and development, software, brands, and marketing—things you can't physically touch but that provide value) in national accounts show significant improvements in measured capital and worker output. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (a U.S. government agency that measures economic statistics) and related research have found that including recognized intangible assets significantly changes how we understand economic growth, especially in service and technology-heavy industries. These updated measurements indicate that intangible assets, including digital investments, have become major factors in production in many advanced economies.

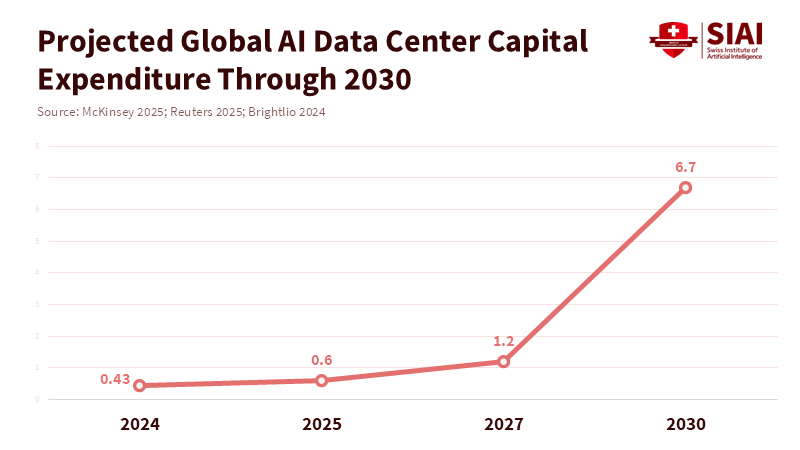

To show how big this is, we can use a simple estimation. If we take the middle estimate of AI's potential impact (about $3.5 trillion per year globally) and assign 30–40% of that to company capital (model building, data sets, organization, cloud infrastructure), we get a capital contribution of about $1.05–$1.4 trillion per year. Also, a separate industry prediction suggests that about $100–200 billion in AI infrastructure spending (data centers, networking, high-performance chips) has been added to global investment through 2024–25. A portion of this spending increases physical capital and should be counted as investment. When national accounts fail to properly record these flows by treating them as immediate expenses or by ignoring changes in quality, measured GDP can underestimate real production by billions or trillions of dollars in large economies. The exact number depends on reasonable assumptions, but the key point is that the amount missed is large enough to change policy decisions.

How This Affects Education, Administration, and Policy

If capital is not being properly accounted for, education is where these issues must be addressed. Traditional education that focuses solely on specific software skills or outdated IT training categories will miss the most valuable skills that create value when AI is used as capital. These skills include data management, prompt engineering as a form of system design, evaluation skills, and the ability to change work processes using AI outputs. This means three things must change. First, schools must teach students to design AI as a company asset, rather than just using individual tools. Second, administrative budgets should treat some AI-related expenses as investments in the business. This includes lab access, curated datasets, and faculty time for building reusable educational resources, rather than treating these as one-time operating costs. Third, policymakers should change funding formulas and accreditation standards to reward creations that can be reused and have lasting worth, such as data sets, modular courses, and validated evaluation methods. These changes ensure that both public and private groups create assets that provide long-term services.

Administrators must also change how they purchase and budget for things. Typical line-item purchasing for software or consulting fails to indicate whether a purchase creates a lasting asset. Treating certain purchases as capital would change depreciation accounting, free up cash, and yield clearer measures of return on investment for training programs. It also affects how institutions negotiate with cloud providers and chip sellers. Longer-term contracts that promote portability and reuse can be seen as investments that support the mission of education. Finally, policymakers should invest in measurement projects. For example, an AI intensity index that combines provider data, procurement records, and survey data would give education leaders the information they need to prioritize investments effectively.

Addressing Concerns

Some may argue that counting AI expenses as capital could inflate balance sheets with things that disappear quickly. This is a fair warning. The solution is to have clear definitions and standards. Not every software purchase is capital. Standards must define AI capital as expenses that create redeployable service flows, such as model data, labeled datasets, internal evaluation tools, and systems that enable repeatable processes. National statistical agencies and standards organizations can make these distinctions clear. NIST and its partners can help create these standards. Once agreed upon, they allow auditors to distinguish between long-term assets and short-term consumption. The result is more accurate, not less.

Governance, Infrastructure, and Fairness

Measurement is important for governance. When national accounts undercount AI-related capital, policymakers underinvest in public resources that enable fair access, such as electricity upgrades near data hubs, shared public datasets with privacy protections, and training programs for underserved communities. Industry investment in large data centers and specialized chips can increase overall capacity, but without public frameworks and shared infrastructure, benefits concentrate in companies and regions that already have advantages. Several recent studies point to a noticeable, but uneven, improvement in GDP from data center and chip investment. These improvements are meaningful, but they increase regional inequality if left unaddressed.

This suggests two policy priorities. First, create public-private funding mechanisms that support shared AI investments, such as curated datasets for public use, subsidized computing for universities and small companies, and regional improvements to electricity and networking that lower costs for newcomers. Second, change the way taxes are handled so that investments in reusable educational AI assets qualify for public support and favorable depreciation, encouraging the development of common resources rather than just supporting existing vendors. Both steps help make the benefits of AI more accessible while ensuring that national accounts better reflect social worth.

If the way we measure the economy is flawed, so will our policy choices. By treating many AI expenses as regular costs, official statistics make the economy seem smaller and less wealthy than it is. This affects everything from workforce planning to infrastructure investment. The solution is simple: use a strategy that combines a short-term AI intensity index with longer-term changes to national accounts that clearly identify AI's intangible assets. For educators and administrators, the message is clear: shift from teaching basic tool use to building lasting skills, and treat the creation of reusable data sets, models, and evaluation systems as valuable investments. Policymakers must fund public resources and set accounting rules that recognize long-term AI capital. When we fully account for what we build, our decisions will align with our ambitions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2023). Marketing, Other Intangibles, and Output Growth in 61 Industries (Working Paper). U.S. Department of Commerce.

Brookings Institution. (2026). Counting AI: A blueprint to integrate AI investment and use data into US national statistics. Brookings Economic Studies.

Business Insider. (2025). AI's economic boost isn't showing up in GDP, and Goldman says that's a $115 billion blind spot. Business Insider.

McKinsey & Company. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. McKinsey Global Institute.

OECD. (2024). Digital Economy Outlook 2024 (Volume 1): Embracing the Technology Frontier. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Reuters. (2025). J.P. Morgan forecasts spending on data centers could boost US GDP by 20 basis points in 2025-26. Reuters.

Comment