Protect the Floor, Save the Top: Rethinking the Firm-Level Minimum Wage

Published

Modified

Minimum wages insure routine workers inside firms Shocks tend to push adjustment onto high-skill jobs Policy must pair the firm-level minimum wage with portable support for talent

The increase in South Korea's statutory minimum wage during the late 2010s and early 2020s provides an opportunity to examine how minimum wage laws affect businesses. According to the International Labour Organization, the minimum monthly wage in South Korea in 2017 was 1,352,230 KRW, rather than the previously stated figure. Instead of viewing the minimum wage as just another expense for companies, it can be seen as a form of internal insurance. It sets a standard for routine jobs, allowing for more flexibility in higher-skilled positions when the business faces challenges. This shift has implications for developing talent, fostering local innovation, and ensuring that government investments in training programs yield the expected benefits. This perspective shifts our thinking about minimum wage policy from a broad issue of income distribution to a matter of organizational structure, offering practical solutions to protect both the minimum wage and the ability to perform complex work within the country.

Minimum Wage as Internal Insurance

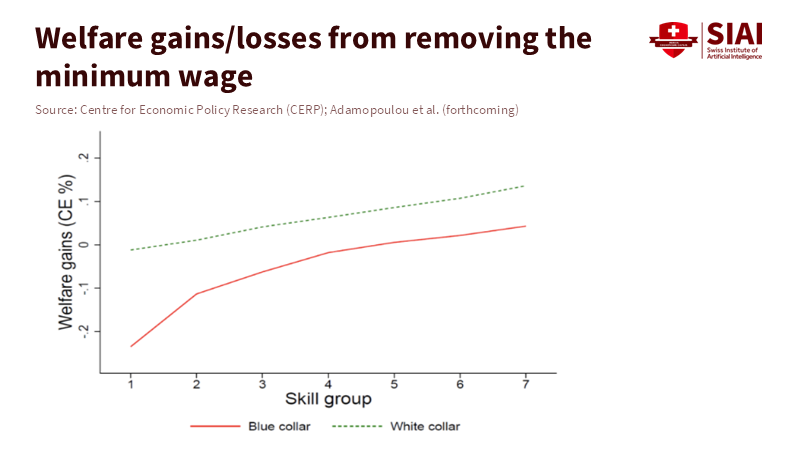

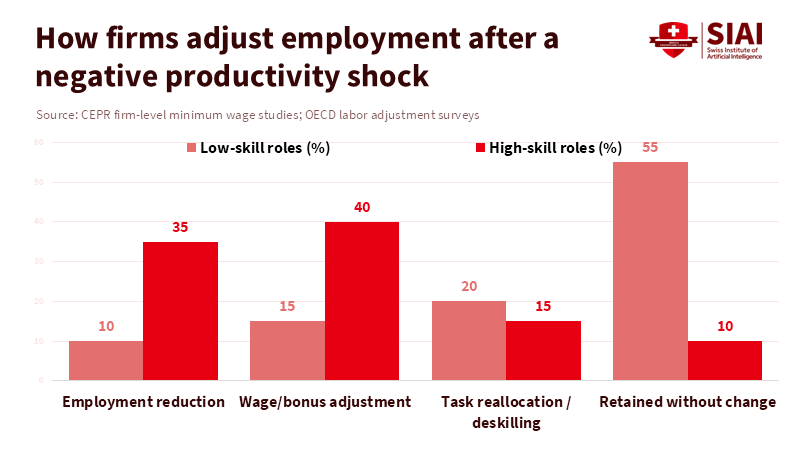

A minimum wage acts like an insurance agreement written into a company's payroll. When sales decline, managers decide where to cut costs. If the base pay for many routine positions is protected by law, adjustments are more likely to affect bonuses, working hours for mid-level employees, or pay cuts and layoffs for those in top-skilled positions. This situation creates an imbalance where lower-paid workers keep their wages but face a greater risk of job loss, while higher-paid workers experience wage reductions and job cuts. Studies have confirmed this pattern, showing that minimum wage laws reduce wage losses at the lower end but increase negative adjustments for higher-paid workers within the same business.

There are three direct consequences to this imbalance. First, companies with few highly skilled workers struggle to innovate, maintaining routine operations but struggling with risky projects. Second, while routine workers benefit short term, the company’s long-term product strategy declines as investment in skilled personnel drops. Third, advanced skill development through apprenticeships, internal training, and mentoring is hurt when top talent is used as a buffer. These effects reach beyond single businesses, influencing public training programs, university courses, and innovation plans, all reliant on returns from advanced skills.

Measuring Impact and Providing Support

Policy debates often gauge overall winners and losers, but this is too broad. For decisive action, measure how many workers at a company earn the minimum wage, and how sensitive higher wages are to company sales. Monitoring these metrics by industry and region would help benchmark risk. Businesses and policymakers could then see when skilled staff are being used as a buffer, and target support more effectively.

Another tool is to provide temporary wage support for displaced high-skilled workers. This support is not just a standard unemployment check but rather a wage-linked payment that helps cover part of a displaced specialist's lost income while they retrain or seek new employment. This support reduces the cost of retaining or rehiring skilled staff and minimizes skill loss during unemployment. Paired with employer-recognized certifications, it preserves the value of advanced skills within the economy. Public funding can be structured in stages, with shorter, full payments that decrease as the worker finds a new job, along with employer contributions tied to rehiring. The goal is to keep skilled workers active in the job market rather than unemployed. A report by Kim Kyeong-pil notes that South Korea’s unemployment benefits can exceed the net income of full-time minimum-wage workers, highlighting a flaw in the country's unemployment insurance structure.

A further step would require companies to report data on minimum-wage employment. A simple disclosure, such as the percentage of employees earning at or near the minimum wage and how their wages change in response to sales fluctuations, can be easily collected through payroll systems. This information helps to better target retraining programs and support for employers. It also influences management decisions, as boards and investors can see when a company is using top-level pay as a shock absorber and can push for better workforce strategies or invest in programs that maintain the company's ability to innovate.

Mobility, Retention, and Talent

The ease with which skilled workers can move across borders changes the situation. When domestic productivity declines, highly skilled workers may choose to move abroad rather than remain underemployed. While this can benefit individuals, it represents a loss for the country, as it loses skilled workers and the return on public training investments decreases. Data indicate high levels of worker mobility into developed countries in recent years, with permanent migration increasing significantly around 2021–2023. This is important for smaller economies that struggle to replace their skilled workforce. Therefore, policies must balance the ability to move with incentives to stay.

When mobility is limited, minimum wage laws can keep skilled workers in the country but push them into lower-quality jobs, slowing productivity and lowering the long-term value of education. This is concerning for markets with less mobility, as public investment in education becomes less effective and public support weakens. The best approach combines portable wage support, rapid retraining, and temporary public funding to support job transitions. For high-emigration countries, focus on retention through tax credits for rehiring, short public projects for displaced specialists, and international exchanges that maintain connections while offering mobility.

Practical Steps

Educators should update certifications to be more transferable and prioritize short, industry-recognized options like micro-credentials and fast-track training. Career services must actively support workers in their job transitions. Universities should partner with industry for short fellowships that rapidly reintegrate workers into the workforce. Such programs should directly address how minimum wage increases shift economic pressures, ensuring that training supports mobility and reduces rehiring costs while maintaining the domestic skill base.

According to the International Labour Organization, administrators should create a national system to track minimum-wage employment and introduce short-term, industry-specific retraining grants, available only if employers invest in retraining their displaced workers. According to a report from Aju Business Daily, policymakers should consider launching wage-support programs targeted at specialized groups such as R&D staff or senior engineers and closely track their re-employment and retention rates against control groups. This approach could help identify which policies retain skilled workers most cost-effectively, particularly given the connection between low domestic pay and the rising overseas employment of these professionals.

It is essential to address minimum wage laws with a commitment to both social equity and economic resilience. Policymakers, industry leaders, and educators must unite to develop strategies that safeguard low-wage workers while sustaining innovation and advanced skills. Demand transparency: publish concrete data on policy impacts, and communicate how portable wage support can maintain the value of domestic training. Push for temporary employer incentives that prioritize rehiring skilled workers. Only by taking decisive, coordinated action can we ensure that minimum wage protections lead to sustainable growth and readiness for future challenges.

Examining minimum wage laws at the company level reveals a trade-off: while a minimum wage protects lower-income workers, it puts pressure on skilled workers. This is not an argument against minimum wages but rather a call to combine them with well-aimed tools that keep talent engaged, mobile within the country, and productive. Start by measuring the impact, creating portable wage support and rapid retraining programs, and funding short-term public projects that employ displaced specialists. These actions maintain the protective intent of minimum wage laws while preserving the benefits of training and innovation. Failing to act within companies will protect lower-wage workers while weakening the base of skilled labor, leading to slower growth and reduced opportunities. The solution lies in policy design; the cost of inaction is predictable and significant.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Adamopoulou, E., et al. (2024). Minimum wages and insurance within the firm. SSRN working paper.

CEPR / VoxEU. (2024). Minimum wages and insurance within the firm. VoxEU column summarizing firm-level evidence.

CountryEconomy. (2025). South Korea National Minimum Wage (USD equivalents). CountryEconomy data series.

International Migration Outlook 2023. OECD. (2023). International Migration Outlook 2023. OECD Publishing.

MacroTrends. (2023). South Korea inflation rate (CPI) 2022. MacroTrends economic data.

Comment