Powering AI data centers: Why the electron gap will reshape the US–China contest

Published

Modified

China’s AI edge is increasingly driven by faster, cheaper access to power and land U.S. grid constraints are slowing large-scale AI deployment and raising costs Energy infrastructure, not code alone, will shape AI leadership

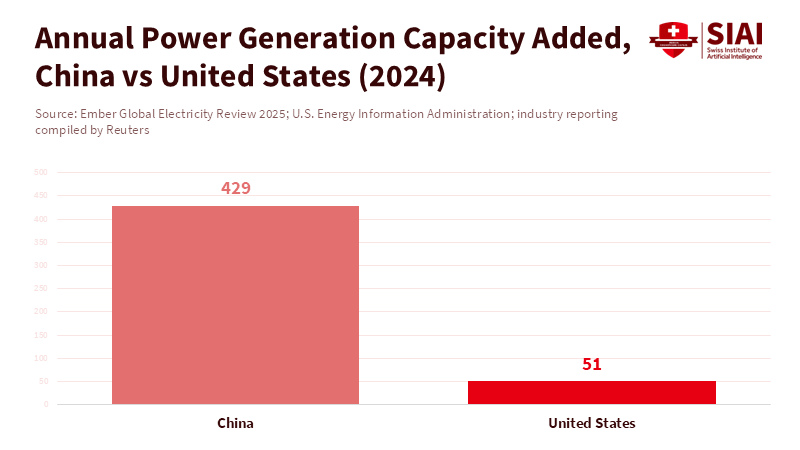

The crucial factor in today's artificial intelligence competition isn't just processing speed or venture capital investment; it's energy capacity, measured in gigawatts. In 2024, China's new power capacity grew by an estimated 429 gigawatts, while the United States added about 51 gigawatts. This difference reflects two distinct approaches: one views consistent, large-scale electricity as a vital public resource, while the other relies on fragmented markets and lengthy approval processes. If electricity supply limits processing power, the country capable of constructing, supplying, and operating large-scale artificial intelligence data centers will have a considerable advantage in speed, costs, and strategic resilience. This isn't just about technology; it affects where research centers develop, which businesses can innovate quickly, and which governments must create the regulations for future infrastructures. Energy capacity for artificial intelligence data centers is a geopolitical strategy more than an engineering issue.

China's Structural Energy Advantage

China's advantage isn't just in the sheer amount of capacity added. It's their combined access to land, centralized planning, and a political system that accelerates project completion. Extensive areas in China’s interior offer flat land close to energy transmission routes. Local governments can synchronize power grid upgrades, set up renewable energy sources, and allocate industrial land. While large companies in the U.S. face various public hearings and interconnection delays that can take years, Chinese projects progress in months. Because of this, their industrial sector can quickly handle large data centers. Energy capacity for artificial intelligence data centers involves providing continuous, affordable energy to co-located computing and cooling systems at the speed modern artificial intelligence demands, rather than installing solar panels or gas turbines.

Specifically, data centers are using more energy than ever. The International Energy Agency predicts that, in a basic scenario, electricity use in data centers will grow roughly 15% annually between 2024 and 2030, doubling to almost 945 terawatt-hours by 2030. This trend favors locations that can quickly add significant capacity and have fewer regulatory or land-use restrictions. China's rapid growth in both conventional and renewable energy sources enables the location and operation of facilities that consume a lot of energy, often using local generation and direct grid connections that are easier to protect than in many U.S. areas. While many Chinese regions face power grid issues and industrial prioritization, the overall picture is clear: China is building the basic infrastructure that makes large-scale artificial intelligence deployments simpler.

The U.S. Energy Shortfalls for Artificial Intelligence

In the United States, the factors that encourage innovation also create issues for the infrastructure needed to support it. Land-use policies, varying levels of required permissions, and an outdated interstate grid result in longer wait times between investment decisions and energy delivery. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that U.S. electricity consumption will reach new highs through 2027, partly due to larger data center requirements, but the growth in energy generation and grid connections isn't keeping pace with commitments from large tech and artificial intelligence companies. These businesses are responding by creating long-term supply agreements and supporting local energy projects. However, these solutions are costly and require levels of coordination that the U.S. system isn't prepared to provide at the scale artificial intelligence now demands.

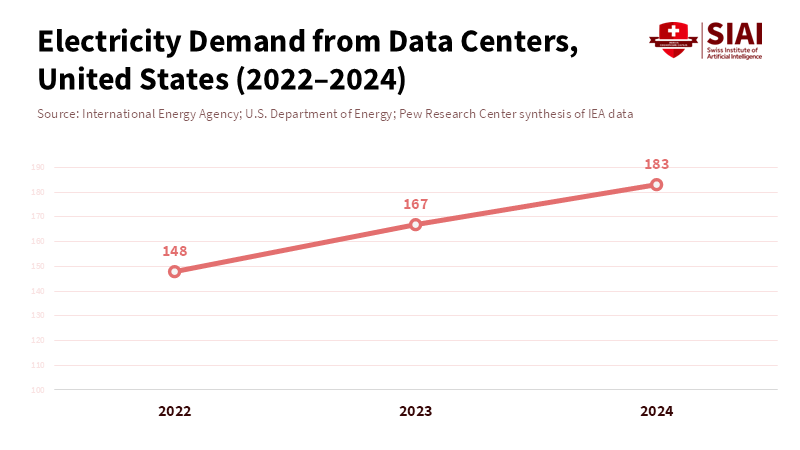

These issues create measurable economic effects. The IEA and other experts estimate that U.S. data centers consumed about 183 terawatt-hours in 2024, a figure that accounts for a significant share of nationwide electricity consumption and is increasing pressure on local electricity prices in areas with new facilities. While a Chinese data center operator can negotiate a local route for a dedicated transmission line, an American operator often deals with multiple utilities, grid connection delays, and market-driven price changes that can significantly raise the actual energy costs. This difference is important because it separates a workable model of continuous, low-cost computing from one that must constantly guard against congestion, price increases, and the risk of outages. Because of this, energy capacity for artificial intelligence data centers reflects financial reality as much as engineering reality.

Strategic Consequences for Education, Research, and Policy

If the presence of dependable, affordable, and secure energy guides where large-scale training and inference clusters are located, then educators and research labs must prepare for a changed environment. For educators, the meaning is clear. Curricula must consider hardware, energy finances, and infrastructure policy as essential skills for future artificial intelligence experts. Learning about algorithms in theory is no longer enough. Students should learn about energy purchasing models, grid connection procedures, and basic energy system stability. For leaders, determining where to locate computer-intensive programs requires a comprehensive risk assessment, including energy contracts, latency considerations, and the track record of locating in areas with challenging power grids. Higher education institutions that have treated cloud credits as the primary capital expense will now face organizational questions about whether to own—or partner with—specific computer networks connected to energy resources.

Lawmakers face tougher choices. They can choose to speed up approvals and expand capacity with public funding, or they can attempt to limit electricity use for high-usage purposes through pricing and allocation regulations. The first option aligns with a mission-focused industrial policy that treats energy capacity for artificial intelligence data centers as a strategic investment in technology independence. The second option protects market rules but risks shifting computing to areas with cheaper, more readily available electricity. In reality, this suggests that the future of advanced artificial intelligence research may depend on whether governments agree on the need for rapid, sometimes centralized, infrastructure decisions. If the U.S. continues to prefer individual, competitive grids with no plans for fast upgrades, it will lose affordability and the chance to gather professionals where the computing takes place. Recent reporting from Reuters and others on China’s narrowing technology gap focuses on how these infrastructure choices complement other key investments.

Addressing Concerns and Considering Counterarguments

One possible point of disagreement is technical. Gains in hardware and software will reduce the increase in electricity consumption. This is partly true. Improvements in model sparsity, chip performance, and cooling can reduce kilowatt-hours per operation. Past data show that performance increases often lead to greater demand that exceeds any savings. The IEA’s models already account for substantial performance gains and still expect rapid overall growth in data center electricity consumption. It has short efficiency delays but doesn't eliminate the need for scale. Another issue involves emissions and climate policy. Critics argue that depending on quick capacity growth risks more use of fossil fuels. Here, the relevant point is policy design. Between 2024 and 2025, China increased the number of its renewable and thermal plants. The outcome for emissions depends on distribution rules, reduction, and fuel types. For the U.S., the policy choice isn't between growth and green results; it's between regulated, coordinated capacity increases that can be low-carbon from the start and unplanned, costly solutions that prioritize short-term speed at the cost of additional lifecycle emissions.

There is also a governance concern: speeding up energy capacity expansion through a centralized, government-led approach could increase monitoring and geopolitical power. That point is serious and real. Infrastructure decisions have political effects. Turning infrastructure over to less effective governance models or to market situations that support only the biggest private players isn't a neutral step. The trade-offs in both the U.S. and China involve control, transparency, and who bears the societal costs. For democratic countries, the policy answer should include speed with protection, such as quick permitting paired with transparency, grid investments alongside community benefit agreements, and energy purchasing that puts low-carbon sources first. This balances affordable capacity inside a rules-based system.

Steps for Organizations and Lawmakers

Universities and research labs should analyze their computing usage now. Analysis should list kWh per experiment, purchasing methods, and backup plans for supply failures. Leaders should consider off-site computing as an energy partner and negotiate energy terms that hedge against local. On the policy side, three steps are useful. Start conditional fast-track interconnection routes for research and strategic computing with environmental and community safety measures. Support regional energy centers that pair renewable energy, storage, and flexible needs to support educational-industrial groups. Ask for transparency in large companies’ power deals so that public organizations understand how they are affected by expenses and societal trade-offs. These actions support growth while protecting public interests.

Operational details are important. Fast-track routes don't mean going around environmental reviews. They mean organizing review steps, standardizing decline, and providing adequate timelines. Energy centers must combine storage with flexible load—research computing can be scheduled to take advantage of low-price windows, if contracts and software allow. The goal isn't to freeze markets but to create predictable, rule-based channels where computing can grow while remaining balanced. If the U.S. chooses to remain slow, its organizations will continue to incur high costs. If it chooses to invest in coordinated infrastructure, it can combine market strength with public purpose.

The artificial intelligence competition depends on more than chips and code. It will come down to who can consistently provide large amounts of affordable, low-emission electricity quickly and predictably, as modern models demand. The 429 GW versus 51 GW comparison is clear because it captures a larger strategic difference: one countrytreates electricity as a tool of nationwide tech power, while the otherlargely treats it as a controlled asset. For educators, leaders, and lawmakers, the policy question is clear. Will we create the rules and infrastructure to support large-scale research and training under clear governance? Or will we allow professionals and computing to go to places where energy is affordable, and rules are simpler? The clear choice is to act quickly while protecting democratic values. Doing so keeps both competition and civic oversight. Handling energy needs for artificial intelligence data centers isn't only an engineering project. It's about the political structure of our technological future, and it needs to be instructed, planned for, and managed with urgency and care.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Clemente, Jude. 2025. “China vs. U.S.: AI Supremacy Requires Reliable Electricity.” Forbes.

Energy Information Administration (EIA). 2026. Short-Term Energy Outlook. U.S. Department of Energy.

International Energy Agency (IEA). 2024–2025. “Energy and AI: Energy demand from AI” and “Global data centre electricity consumption” reports. IEA, Paris.

Office of the U.S. Secretary of Energy. 2025. DOE Final EO Report: Evaluating the Reliability and Security of the United States Electric Grid (July 7, 2025).

OpenAI (reported). 2025. Public briefing summarized in industry reporting on power capacity additions (2024).

Reuters. 2026. “China is closing in on US technology lead despite constraints, AI researchers say.” Reuters.

Stanford Review. 2025. “How China’s Energy Supremacy Threatens U.S. AI Dominance.”

Ember. 2025. “China Energy Transition Review 2025.”

Pew Research Center. 2025. “What we know about energy use at US data centers amid the AI boom.”

Comment