Robot tax is no longer a joke: why revenue design must catch up with automation

Published

Modified

AI-driven automation is shrinking both labor and consumption tax bases A robot tax is becoming a practical fiscal tool, not a provocation Welfare systems may also need less funding as labor is partially emancipated

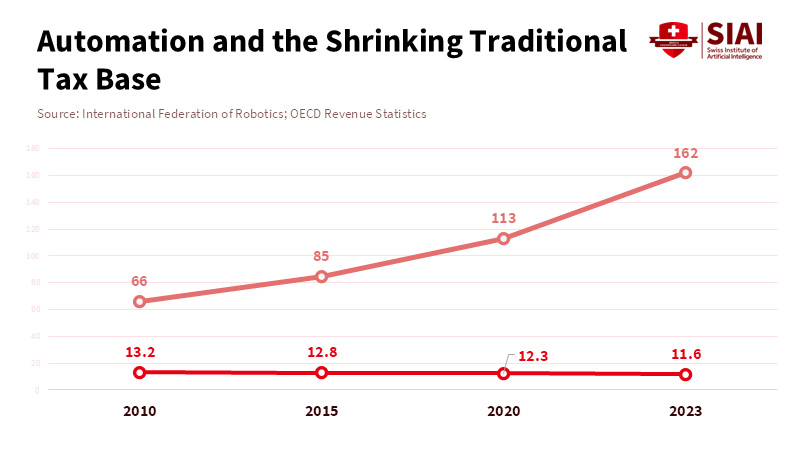

In 2024, the average density of robots in factories was approximately 162 per 10,000 employees. In certain countries, this figure is now in the hundreds. This development isn't a future possibility; it reflects the present state of production. As automation increases capital's share of output while reducing the need for routine labor, two related tax bases become unstable: income taxed at source and the spending resulting from earned wages. The arithmetic is straightforward, but the political implications are complex. There's a reduction in payroll and personal income tax receipts, along with smaller VAT bases if incomes decrease. The phrase "robot tax" was once considered controversial. could be interpreted as a warning: governments must decide either to disregard the decrease in the tax base, or to change revenue regulations to ensure that public services and social security continue to exist throughout the automation wave.

Why a Robot Tax Is a Serious Consideration

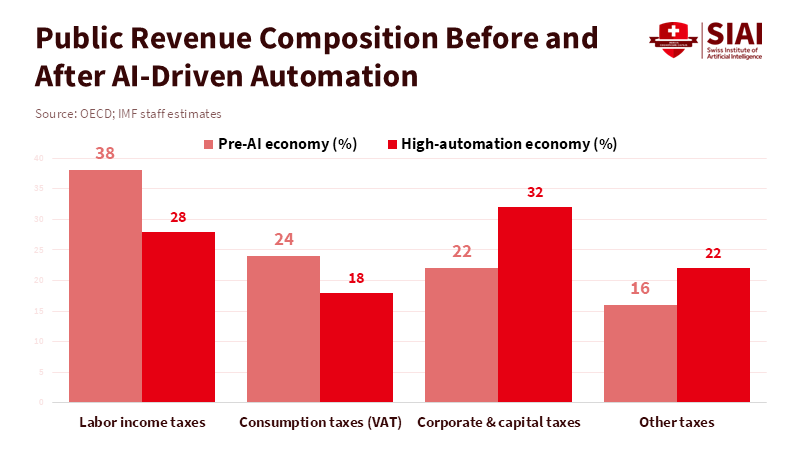

The key idea is quite clear. Modern automation increases the capital used in production and, assuming all other factors remain constant, lowers the share of national income received as wages. When salaries decline, consumer spending tends to fall as well. A sizable share of public revenue in most developed countries comes from taxes on work (payroll taxes and personal income taxes) and consumption taxes like VAT. Because automation reduces both earnings from work and spending, the combined decrease of these bases creates the possibility of long-term deficits if tax systems are not adjusted.

Recent data shows this trend. In OECD countries, social contributions and personal income taxes combined accounted for roughly half of total tax revenue in the most recent year for which consolidated data were available. VAT and related consumption taxes made up about one-fifth. At the same time, there has been a sharp increase in robot installations and robot density. The average number of robots globally has doubled in recent years across several manufacturing centers, with China and other economies growing especially rapidly. Separately, working-age populations and employment rates differ, but surveys reveal widespread concern among workers about how AI will change job duties and lead to job losses. Taken as a whole, the math is concerning. An increase in the capital share, combined with lower wage growth, could reduce two of the three primary sources of income for many governments: wages and consumption. The third source, taxes on businesses and capital, might seem like a solution, but it comes with political and practical problems. Businesses can move their profits, try to influence policy, or change investment costs. Heavily taxing capital could discourage productive investments if not done carefully.

Therefore, talking about a robot tax is more than just talk. It represents a range of policies, such as taxes on the use of automation, higher taxes on capital, broader taxes on profits from economic activity, or new user fees. These are meant to stabilize income in an economy where machines do a larger share of the work. The discussion is not only about collecting income from robots. It concerns how value should be claimed publicly when private machines generate more of it. The political importance is great. Governments must either change to guarantee income for public services and social insurance, or they must allow insufficient funding for welfare programs and growing inequality to continue.

Where Public Revenue Will and Won't Come from in an AI Economy

To accurately estimate the areas where tax revenues will fall short, thorough and open estimations are needed. Yet, various reliable patterns are already showing: (1) Across numerous sectors, labor's share of earnings is under pressure; (2) Consumption is still the biggest single driving force of demand in the majority of countries; and (3) The use of robots and AI is most common in areas that formerly offered numerous middle-income jobs. These three realities turn the dual risk of VAT and payroll taxes into a real danger.

To the point, consider this conservative calculation: In a developed economy, suppose employee compensation decreases by 5% in relation to GDP over a ten-year compression era. If families' marginal inclination to spend from labor income is 0.6, and their final consumption accounts for around 55% of the GDP (these total metrics are consistent with many totals from the World Bank and OECD economies), then a 5% decrease in the amount earned from work could lead to a 1.65 percentage point decrease in spending as a proportion of GDP in a steady state (0.05 × 0.6 × 0.55 ≈ 0.0165). With VAT income normally in direct proportion to consumption, a comparable drop in VAT income is possible without a counterbalancing policy. This is a simplified model for illustrative purposes; it presumes no offsetting fiscal transfers, no corresponding salary increases in other fields, and no immediate policy demand to stabilize. The intent is not to provide precise numbers but to indicate scale: even small drops in labor income result in noticeable declines in consumption tax bases.

Other options for making money may look good on paper, but come with restrictions. Taxes on capital gains and corporate income can capture a part of the new value produced by machines, particularly when automation increases company earnings. Yet corporate tax income is already unpredictable and prone to avoidance. Higher taxes on wealth or increased top rates on capital income may be helpful, but they often face political opposition and are administratively costly. New taxes tied directly to automation, such as fees on robot installations, increased taxes on depreciable capital accelerated by AI, or a surcharge on the use of AI deployments for business, may be created to track the degree of automation. Yet any tax on productive capital carries the risk of weakening adoption and financial expansion unless it is precisely targeted and phased in.

Lastly, outcomes differ greatly across countries. Countries with fast automation and weak social security will face tighter budget constraints sooner. Nations with strong public services but slower automation expansion may be protected for longer. The result will be differing budgetary pressures rather than a single, global disaster, which policymakers should consider when creating cross-border tax cooperation.

Designing Realistic Robot Tax Policies That Protect Expansion and Fairness

Policy needs to accomplish three objectives at once: guarantee steady revenue, preserve incentives for productive investment, and maintain equal distribution outcomes. While this is a difficult set of goals, it narrows the options to only the practical ones. To start, broaden the base on which capital taxes are applied in ways that are easy to manage and hard to exploit. This entails stronger regulations against profit shifting, greater tax collection of algorithmic and digital rents, and well-designed tax systems with minimum rates enforced in practice. Tax regulations shouldn't promote displacement through overly generous write-offs or depreciation plans if automation delivers quick gains in work efficiency. Specific actions, such as a small fee on accelerated capital allowances, for instance, could increase revenue without halting investment in supporting capital that widens job opportunities for automation that substitutes for labor.

Second, consider usage-based taxes that mimic how society already taxes other movable capital. For example, automobiles are taxed through insurance, gasoline taxes, and registration fees, which reflect the social costs. Similar ideas can be applied to robots and autonomous systems. A per-unit registration charge for industrial robots, a safety and liability charge for robots working in public spaces, or a transaction fee for commercial AI services could generate stable income while promoting safety and shared standards. The fees are not a tax on innovation in and of themselves; they are a funding tool that accounts for social costs and finances safety nets, training, and monitoring.

Third, combine revenue changes with spending redesign. Governments can redirect funds freed up by automation towards transitional wage supports, retraining initiatives, and lifelong learning if automation reduces certain welfare costs (such as lower long-term health burdens from repetitive work). Those are the public goods that go well with private automation. In some situations, governments may, in the long term, require less headline spending on transfer programs. But the need for active labor-market policy and retraining is the most believable near-term outcome. For this reason, policymakers ought to tie new income streams to investments in community digital infrastructure, job-transition services, and education. Creating that connection helps keep support for new taxes while making automation more inclusive.

Fourth, coordinate tax policy across national borders. AI services and digital cross-national lines. A race to the bottom will ensue when countries adopt widely differing regulations, and earnings will shift. Standardized reporting of automation intensity, multilateral agreements on how to treat algorithmically produced rents, and coordinated minimum tax floors will reduce arbitrage and stabilize revenue.

Lastly, invest in early warning systems and real-time data. Tax law requires a stronger sensor network to identify structural changes, such as employer-employee data that matches the VAT receipts by sector, and the automation adoption indexes. With better data, governments can set tax rates so they rise when labor markets get worse and fall when overall employment improves. This active approach lowers blunt distortions and focuses policy where it is most needed.

The educators and administrators have immediate effects. Universities and schools shouldn't promise the static degrees that go with jobs of the past. Education ministries must budget for pathways with continuous learning, create micro-credential stacks that stack into recognized degrees, and collaborate with industry to track which tasks are being displaced by automation. Instead, curricula ought to be linked to civic skillsets directly - digital stewardship, adaptability, and the human skills that go well with AI. Administrators will require new measurement standards of institutional success. They also include stable job transitions, earnings, and not just graduate placement during the first six months.

By anticipating potential criticisms, the design is strengthened. Others will argue automation boosts productivity enough to widen the tax base, while some will claim the “robot tax” will suppress expansion. That's the old dispute over compromise. However, loopholes and poorly designed tax systems already misprice automation today. Automation of simple labor can be charged a small, transparent usage fee or covered by a modest surcharge. Social buffers would be funded, and contributing investment would be preserved. Productivity gains, however, are typically focused on as rents, not wages, in the medium to short term. The profits will not translate into shared welfare or stable revenue without methods to collect a portion of those earnings for community purposes.

A Useful Plan for the Years ahead

We can admit three awkward facts. The first is that public income depends on automation, shifting income toward capital. The second truth is that regular tax tools, such as payroll taxes and VAT, are affected by the shift. The third is that unthinking responses risk either starving public services or stifling innovation. A sensible balance involves a functional bundle. Modernize tax collection and anti-avoidance for capital, introduce precisely targeted usage fees and safety charges for automation, and link new income to investments in transition supports and lifelong learning. The bundle treats the robot tax as a design challenge rather than a slogan.

For administrators and instructors, it's clear that students need to be prepared for a job market where human work is defined by digital stewardship, social intelligence, and judgment. For the policymakers, fiscal engineering is the job under democratic restraints- creating tools that fairly collect economic rents, support public services that make automation socially sustainable, and stabilize incomes. We will avoid the worst outcomes if we treat the coming change as an opportunity to reset the contract between earnings, wealth, and public claims. We will be forced to make harder choices later if we avoid it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

International Federation of Robotics. (2024). World Robotics – Industrial Robots: Executive summary and robot density statistics.

International Monetary Fund. Velasquez, A. (2023). Production Technology, Market Power, and the Decline of the Labor Share (IMF Working Paper).

ILO. (2024). Global Wage Report 2024–25.

OECD. (2023). Revenue Statistics 2023.

OECD. (2023). Employment Outlook 2023.

OECD. (2024). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Productivity, Distribution and Growth.

Reuters. (2024). China overtakes Germany in industrial use of robots, says report.

The Guardian. (2024). AI may displace 3m jobs but long-term losses 'relatively modest', says Tony Blair's thinktank.

World Bank. (latest). Households and NPISHs final consumption expenditure (% of GDP) — World Development Indicators.

Comment