Fewer Than One in Five: Why the AI Hype Still Misses Most European Workplaces

Published

Modified

AI adoption in Europe is still limited, with most firms using AI only as a supporting tool The gap between AI hype and real workplace use reflects risk, skills gaps, and institutional limits Policy and education must focus on practical capacity, not promises of rapid transformation

In 2025, less than one in five European companies says they formally use artificial intelligence. This number paints a more realistic picture than the idea of a fast-paced move toward automation, and it brings up a valid question for those who make policy and teach: If AI is truly changing work, why isn't it used in most workplaces? The answer isn't resistance or lack of awareness, but rather has to do with structure. Across Europe, AI use is inconsistent, basic, and often just for show. Many companies use AI as a tool, not as a core system. This difference between what people think and what's really happening is important now because policies, funding, and training plans are starting to assume that AI is everywhere already. They're being created for a future that isn't here yet. Until we recognize what AI use in Europe actually looks like, investments will continue to reward hype over real work, and training programs will prepare workers for tools they may never need.

AI use in Europe: what the numbers tell us

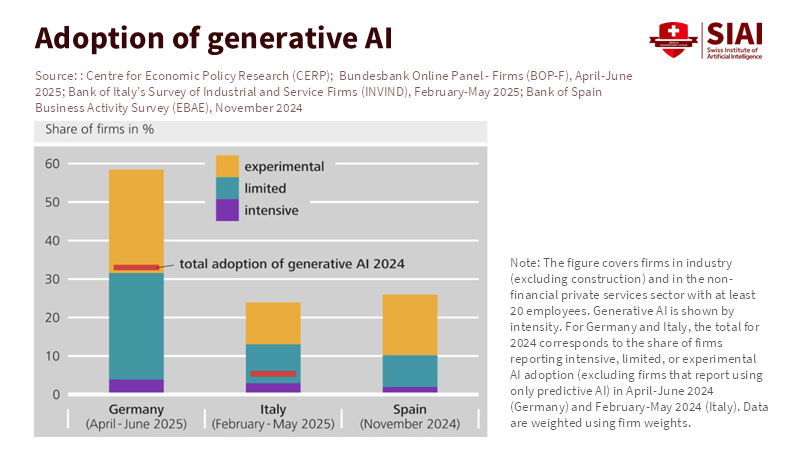

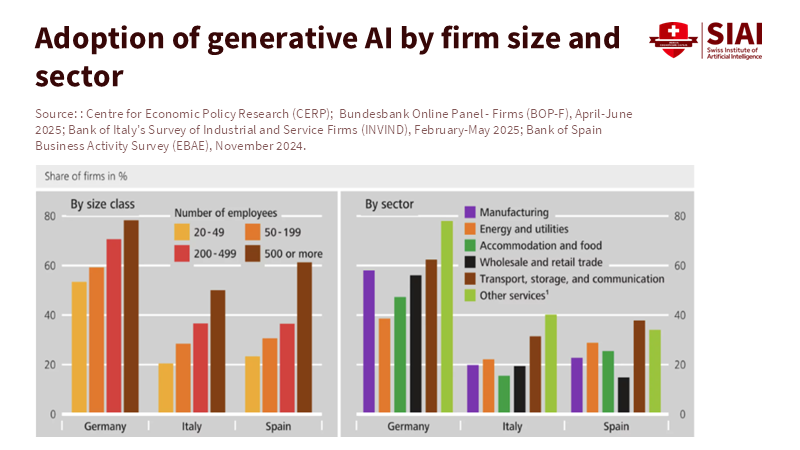

Recent surveys of businesses across the European Union show a common theme. About 20% of companies say they use AI in some form, mostly big companies and those in knowledge-based fields. Among small and medium-sized businesses, where most Europeans work, the numbers are much lower. In some countries, such as Italy, fewer than 1 in 10 companies report using AI. These aren't just unusual cases. They come from official statistics that define AI narrowly and ask companies to report when they intentionally use it, not just when it's part of a software update.

This is an important point. Many companies use digital tools with machine-learning components without calling them AI. At the same time, some companies say they've adopted AI after doing small tests that never became part of their daily work. These things balance each other out. The result isn't exact, but it gives us a good idea of the trend. AI use in Europe is growing, but it's starting from a low base and remains inconsistent across company sizes, industries, and countries.

The popular story of quick spread comes from different sources. Consulting surveys and reports from sellers often claim that half or more of companies are using AI, especially generative tools. These surveys often focus on tech leaders, executives at large companies, or early adopters. They measure interest and experiments, not ongoing use. Both views are helpful, but they tell us different things. One tells us how many companies depend on AI as part of their usual work. The other tells us how many are curious or trying things out. Confusing these two can lead to bad policy decisions.

This reality has direct results for those who teach and run programs. Training systems are being changed to focus on general AI knowledge, as if every workplace needs it. But many companies need workers who can judge tools, handle data quality, and use small AI functions in their current work. Teaching advanced AI use without covering these basics could widen the skills gap with employers' needs. The policy challenge is not to assume everyone is using AI, but to help companies move from curiosity to skill.

Why AI is still a helper, not a main system

Across both Europe and the United States, surveys of workers show a similar story. About one in five adults say they use AI tools at work, and even those who do mostly see them as helpers, not replacements. They help write emails, summarize documents, or brainstorm ideas. They rarely control important decisions, schedules, or how things are made. This isn't by chance. It shows how companies handle risk.

Being correct is still the first problem. AI systems, especially general tools, still make confident mistakes. For tasks where mistakes can lead to legal, financial, or safety problems, companies prefer human judgment. Using AI to help write a draft is safe, but using it to make a final decision is not. Until it becomes more reliable or until better ways to assign responsibility emerge, companies will keep AI in low-risk areas.

Skills and the ability to make changes form the second problem. Using AI means having good data, changing processes, and regularly checking on things. Big companies can handle these costs, but most small companies can't. For them, using AI often means buying a ready-made tool that fits into their current work without changing it. This limits how much they can gain, but also how much disruption it causes.

The third problem is uncertainty. Companies face changing rules, unclear responsibilities, and rapidly changing seller options. Tying a key process to a specific AI system feels risky when standards are still changing. Using it a little at a time becomes the logical choice. This is why AI use in Europe seems basic from the outside. It's not because companies don't see the potential, but because they're being careful within their limitations. Policy should start with this understanding, not with frustration.

Critics often point to successful companies that have already changed their operations using AI. These examples exist and are important, but they're not typical. They have strong data systems, skilled workers, and leaders who are willing to change work from the ground up. The danger is creating policies for these exceptions instead of for the average company. When that happens, public money goes to experiments that don't expand.

The policy mistake: thinking use is unavoidable

Many current policies assume that AI use will speed up on its own, as long as rules don't get in the way. This assumption shapes training plans, funding for new ideas, and even job market predictions. But it's wrong. Technology spreading is rarely automatic. It depends on related investments, trust in institutions, and changes in how organizations work. AI is no different. Without help for using it, adoption stops at the test stage. Research shows that gains come not from the technology itself, but from how it changes tasks and decisions.

For education systems, this means a change in focus. Instead of making broad claims about AI-ready graduates, courses should focus on practical skills. Students and workers need to know how to check outputs, handle data, and change workflows to fit imperfect tools. These skills can be used across different platforms and industries, and they're what companies really need.

Government buying offers another way to make a difference. Governments buy a lot of digital systems, but often reward newness instead of use. Contracts should require clear plans for changing workflows, training staff, and measuring results. This would show sellers and companies that AI adoption is not about demos, but about lasting use. There's also a role for shared resources. Many small companies can't afford to hire data engineers or AI checkers. Regional support centers, industry-specific support, and neutral evaluation centers could make adoption more affordable. This isn't old-style industrial policy; it focuses on making adoption possible rather than trendy.

Skeptics say these steps slow the spread of new ideas. But they actually do the opposite. By reducing uncertainty and spreading knowledge, they help more companies move beyond basic use. The alternative is a two-speed economy: a few advanced users and a large group watching from the sidelines.

From hype to habit: what lasting adoption needs

The last change is about culture. AI adoption in Europe is often seen as a competition with other regions. This encourages speed over suitability. A better way to think about it is to form a habit. Companies adopt what they can keep up with. Habits form through repetition, feedback, and trust.

To build these habits, policy should reward consistent use rather than big announcements. Metrics should measure how deeply AI is used, not just if it's present. Education systems should confirm practical skills, not just knowledge of tools. Those who make rules should focus on clarity and fairness to reduce fear of unknown responsibilities.

Teachers, especially, are at a key point. If they teach AI as magic, graduates will expect workplaces that don't exist. If they teach it as a fallible system within social and organizational contexts, graduates will be better prepared for real work. This isn't lowering goals, but redefining what it means to be ready.

The opening number is worth repeating because it sets the foundation for the discussion: less than one in five European companies use AI today. This isn't a failure, but a starting point that yields several key takeaways: current AI use is limited, policy and training should align with actual adoption, and real productivity comes from grounded, step-by-step integration. Policies built on this reality can make AI adoption more meaningful and productive, rather than driven by hype.

Creating a policy for Europe that is

The gap between AI headlines and what's really happening in workplaces isn't going to close on its own. It continues because policies, education, and investments have been built on assumptions rather than facts. AI adoption in Europe remains limited, inconsistent, and largely used as a helper. Pretending otherwise doesn't speed up change, but distorts it. A better way is to start with honesty. The key takeaways are: most companies are cautious with good reason, AI is mostly a workplace helper, and actual productivity depends on how technology is used, not just on exposure to it. Policies that reflect these truths will better support slow, meaningful progress: skills development, thoughtful workflow changes, and building institutional trust. The challenge ahead is not to force adoption, but to make it possible. This means matching education to real needs, government buying to real results, and rules to real risks. If Europe succeeds, it will be because it moved deliberately, not because it moved fastest. The future of work won't be announced; it will be built, one workflow at a time.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. (2025). How are Americans using AI? Evidence from a nationwide survey.

CEPR / VoxEU. (2026). Embracing AI in Europe: New evidence from harmonised central bank business surveys.

European Commission (Eurostat). (2025). Use of artificial intelligence in enterprises.

McKinsey & Company. (2024). The state of AI in early 2024: Gen AI adoption and value capture.

OECD. (2025). The adoption of artificial intelligence in firms.

Reuters / Istat. (2025). Italian firms lag in AI adoption.

Comment