Industrial Echoes: Why an AI-driven divergence will reshape who prospers — and what educators must do

Published

Modified

AI is triggering a new global divergence, much like the industrial revolutions before it Countries that control AI systems and skills will gain lasting economic and institutional power Education and policy now decide who leads and who is left behind

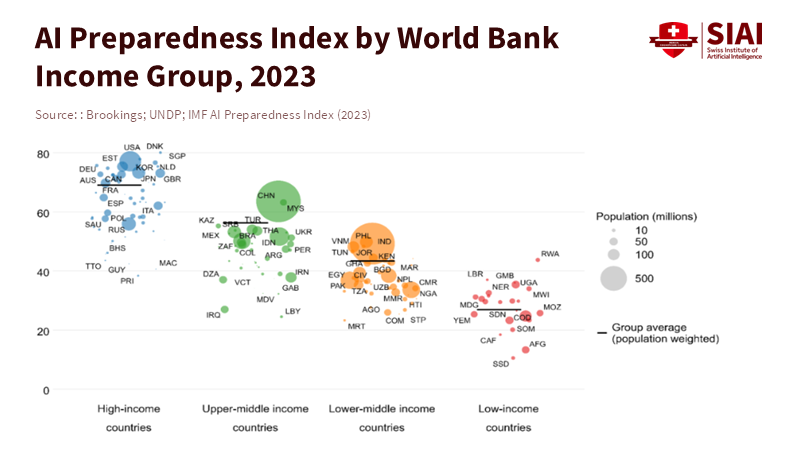

A potential divide, spurred by advances in artificial intelligence, is emerging, and its advantages may not be shared equally across the globe. History offers some parallels. In the 18th century, a select few countries transformed their economies from agriculture to industry, gaining a head start that lasted for decades. Later, in the late 20th century, a smaller group of countries mastered computer and mobile technologies, again pulling ahead of the rest. Currently, a similar pattern seems to be forming around AI. The concentration of advanced AI models, computing power, investment, and skilled professionals in specific systems and regions is creating a new form of advantage. Those who adopt these technologies early do not just get ahead faster; they also reduce the cost of creating value with each subsequent improvement. Lowering the cost of tasks once performed by numerous workers enables a limited number of countries and companies to increase output with minimal labor costs. This situation has implications for educators and government officials. They must adjust educational programs, institutional focuses, and national plans now, before this unequal advantage becomes irreversible, leading to long-term stagnation for many.

Why AI concentrates advantage faster than previous revolutions

This AI-driven divergence echoes historical trends. A few entities adopt ground-breaking technologies, build systems around them, and reap significant rewards, while others fall behind. We saw this with mechanized textile production, coal and iron industries, and, more recently, with semiconductors and the internet. Compute capabilities, data resources, and engineering expertise are at the center of the current advantage. Private investment, model growth, and cloud computing resources are primarily concentrated in a handful of countries and firms. For instance, in 2024–2025, private AI investment in the U.S. exceeded that of other countries. Model releases and advanced computing power were also concentrated among a small number of companies and platforms. These concentrations create feedback loops: greater investment leads to better models, which attract more users and generate more data and expertise, which, in turn, widens the gap. While not inevitable, this trend is self-reinforcing without appropriate policy interventions.

Looking at real-world usage, the adoption of generative AI increased greatly through 2024–2025, but it is not universal. According to a study, only a minority of people use generative AI tools regularly, with higher adoption rates in more affluent countries. This is important because active adoption builds valuable skills. Regular and skilled users develop strategies, learn suitable tooling, and create workflows that increase productivity. Where adoption is limited, tools may remain unused or be used improperly, resulting in low-value outcomes and failing to deliver lasting productivity gains. In essence, access combined with knowledge leads to advantage, whereas simple access without knowledge does not. It should be noted that utilization numbers are based on reports from companies, institutions, and national surveys. Discrepancies have been addressed by using conservative averages.

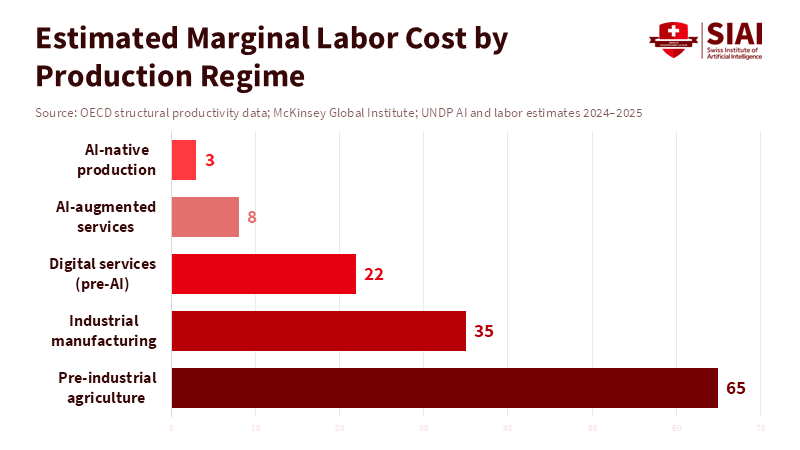

The collapse of marginal labor cost and global market power

A key trait of advanced AI systems is their ability to perform many knowledge-intensive tasks at a lower cost than human labor. This is not hyperbole. AI models can duplicate text, translate languages, generate code drafts, and handle complex questions repeatedly without requiring much human input. When companies in leading countries utilize these systems on a large scale, the cost of services can decrease greatly. The financial result corresponds to the rise of factories: producers using machine-driven processes can offer lower prices than their competitors and gain control of the global market. The difference today is the speed and reach of these technologies. Entire white-collar jobs, such as research, initial drafts of legal documents, and standardized medical recommendations, can be automated. According to Axios, most lower-wage workers are concerned that artificial intelligence could threaten their job security and limit economic mobility, suggesting that advances in AI may reduce demand for certain middle-skill jobs and influence wages worldwide. The businesses that scale early gain benefits by being the first to use the technology.

When the cost of replicating services approaches zero, leading companies do not simply grow; they secure their market control. Historical parallels can be drawn: textile factories in the 19th century were run by producers who automated their operations, while chip-making centers in the late 20th century set industry standards. A modern-day parallel is the AI stack—the combination of models, computing power, data management practices, and user interface design—that very few countries can completely control. This has geopolitical implications: countries that ground their industrial activity and public services on their own independent infrastructure preserve their policy-making freedom and gain financial benefits. Countries that lack these infrastructures may become dependent on foreign platforms for basic services, exporting raw data or simple services instead of developing high-margin products. This centralization is apparent in the number of computing resources and AI models, as well as warnings from organizations that indicate increasing risk if access gaps continue.

Education and policy as the last line against AI-driven inequality

With the advantage going to those who combine infrastructure with skilled usage, education becomes a critical ground. The goal is not simply to teach students to use specific AI tools. Instead, learning should be redesigned to blend tool knowledge with critical judgment, data handling skills, ethical reasoning, and system design. Educational institutions should produce graduates who can find where AI adds value, verify the output of AI models, and incorporate AI in collaborative workflows with people. This requires some change to educational programs. First, applied AI prompt engineering, model review, and essential data statistics must be added to standard courses so that students can test and validate the AI’s outputs. Second, data management and data privacy principles should be taught across all subjects, so that institutions can form partnerships that protect benefits when models from other countries are utilized. Third, vocational training and mid-career training programs should be expanded with modular certifications tied to local industry needs. These adjustments are crucial for national stability in an economy shaped by AI.

Teaching should incorporate collaborative projects that involve both humans and AI. For example, students can work together to design and evaluate AI systems for practical tasks. They can then think about the AI’s defects and biases. Schools should allocate funds to labs that include access to AI models, safe computing areas, and ethical oversight. Government officials can support this by funding regional computing clusters and public AI models, lowering entry costs for smaller institutions. Without these actions, classroom training will not be enough, and graduates will not have the practical skills needed to be valuable users rather than just producers of poor outputs. The biggest risk is not unemployment; it is a future of underemployment, in which people are stuck in low-value roles because they lack proper mastery of the tools.

Some may say that technology alone doesn't determine a country's long-term financial prosperity. Institutions, geography, and political will also matter. This is valid. Technology increases both strengths and weaknesses, but it cannot create them. Others may rebut that model decentralization and edge computing will quickly democratize power, thus softening any significant split. This is possible, and some research already shows how this could work. Personalization requires investment in chips, engineering, and maintenance resources that are scarce outside leading economies. Another possible argument is that late adopters can catch up by skipping certain steps. This is also possible, but it requires careful government funding and diplomatic actions to ensure fair access to computing power, talent, and public data structures. Otherwise, late adoption could look like dependency rather than catching up.

Effective policy actions include public spending on computing power and connection infrastructure, technology transfers that build local capability, education changes tied to internships, and protections that prevent value capture by foreign platforms without sharing profits locally. Organizations are already sounding the alarm about this. Multilateral reports suggest investing in people and digital independence to prevent inequality between states. The technical and political approaches will depend on the country, but the goal is to turn AI from an extractive force into a capability owned at home. If not, their economy may be split into an AI-supported core and low-margin periphery.

In conclusion, an AI-caused divergence will be a drawn-out process that includes infrastructure, capital, and human capital building over the years. The historical parallels are strong because the systems are alike: those who learn the new technology early make lasting achievements. For educators, the best approach is adaptation. They should remodel educational programs, invest in shared computer access, and design partnerships that keep most of the value at home. If countries act now to turn access into ability, AI can become a global opportunity rather than just another industrial enclosure. Nations that delay this transformation risk assigning regions to the role of spectators, providing raw inputs to systems managed elsewhere. The opportunity to affect whether AI becomes a force for the greater good or a source of global inequality is here now, and educational systems must act.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Anthropic / Microsoft / industry diffusion reports. (2025). AI diffusion and compute concentration. Industry white paper.

Brookings Institution. (2026). The Next Great Divergence: How AI could split the world. Brookings Essays.

LSE Public Policy Group. (2025). Will AI create a new Great Divergence? LSE Articles.

McKinsey & Company. (2025). The State of AI: Global Survey 2025. McKinsey Insights.

Microsoft AI Economy Institute. (2026). Global AI Adoption in 2025. Corporate report.

Reuters. (2025). AI could increase divide between rich and poor states, UN report warns. Reuters Technology.

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). (2025). AI Index Report 2025. Stanford HAI.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2025). The Next Great Divergence: Why AI May Widen Inequality Between Countries. UNDP Policy Report.

World Trade Organization / Financial Times reporting. (2025). AI risks widening global wealth gap. Financial Times analysis.

Comment