Survival of the Fluent: Why the AI fluency gap Will Reorder Work and Schools

Published

Modified

The AI fluency gap is becoming the new digital divide, reshaping who advances and who falls behind at work Only a small group of fluent users capture most of AI’s productivity gains, concentrating power and opportunity Education systems and policy must act now to make AI fluency a shared public skill, not a private advantage

The most vital skill in the coming years won't be coding or a specific degree, but rather the ease, almost second-nature, with which one can apply artificial intelligence. According to Sci-Tech Today, in 2025, 78 percent of global companies were using AI in their daily work, and over 70 percent had incorporated generative AI into at least one business function, indicating that this technology is already transforming teams and industries, even though universal adoption is not yet the norm. This difference is important because AI skills grow quickly. Those who use AI regularly improve faster, tackle bigger problems, and are offered better jobs. Those who don't will fall behind, and not just a little. This creates a divide, not between those who have computers and those who don't, but between those who are skilled with AI and those who aren't. As history suggests, the most successful people won't be those who first start using AI, but those who learn to think through its use. Schools, employers, and leaders must plan to help those who are struggling, rather than expecting everyone to catch up on their own. The question isn't whether AI will change work, but whether we can guide that change to benefit many, not just a few.

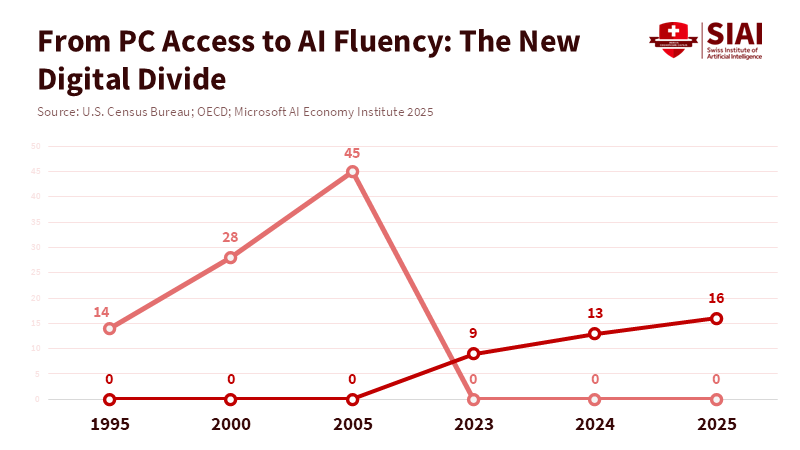

The AI skill gap repeats the problems of the PC era

The arrival of personal computers in the late 20th century changed job opportunities. People who quickly adopted the new technology gained a significant advantage. Others who resisted or learned too late found themselves in less important roles or out of work. This wasn't unavoidable; it was the result of how quickly computer skills became necessary for everyday work. We're seeing the same thing now with AI, but much faster. While using a PC required knowing how to use a keyboard and learning new habits, using generative AI requires being able to frame problems in ways the AI can provide useful, new answers. Then, one must edit, review, and add those answers to the organization's work. Skill isn't just one ability, but a collection: the ability to write good prompts, to judge the results, to design systems, and to know when AI helps and when it misleads.

AI is spreading unevenly, benefiting a small group. Studies from 2024 and 2025 show interest in AI at many companies, but few workers use it regularly. In some areas, about 16% of users were using generative AI regularly by late 2025. Many workplaces have a few highly skilled people, while most use AI sparingly or are unsure how to use it. When skill is concentrated, it affects who leads projects, who writes code or reports, and who gets promoted—impacting influence and income.

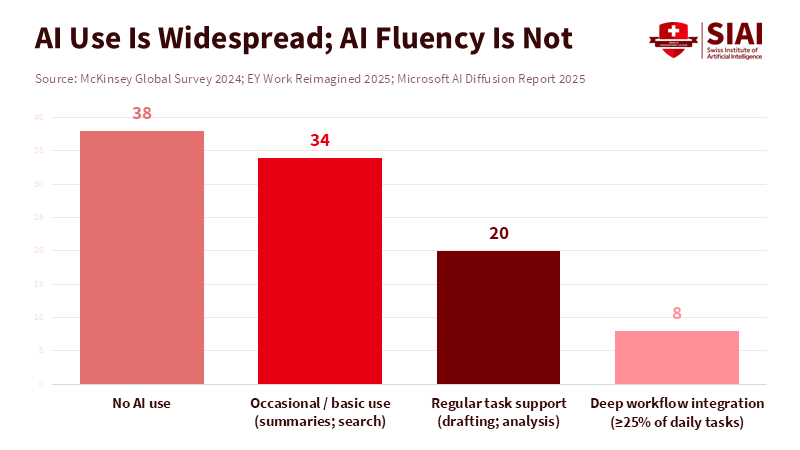

AI skill is not a simple yes-or-no. Some workers use AI for simple tasks like summarizing or scheduling. Others have included AI into entire workflows, such as writing in-depth analyses, generating product ideas, or automating reports. The main difference is the extent and automaticity of use. Basic use makes things easier. Deep use changes how work is done. A skilled analyst can oversee AI models that do the work of three or four less-skilled colleagues while improving creative output. This multiplying effect is why skill results in a major advantage.

How unequal adoption creates winners and losers in the job market

This happens through two related ways. First, AI increases a skilled worker's output in a day. Second, once AI handles routine tasks, the jobs left for people require more judgment, design, and the ability to combine information from different areas. These abilities are easier to practice when one regularly uses AI as a partner. Surveys from large consulting firms and research groups in 2024 and 2025 show a clear gap between the extent to which organizations have adopted AI and the extent to which they use it regularly. Firms report that AI is widely used, but only a few employees say it accounts for a large part of their daily work. In other words, AI is present, but its power lies in the hands of those skilled in using it.

A 2025 study estimated that about 1 in 6 people worldwide used generative AI tools regularly. In the European Union, around 30% of workers were using AI at work by late 2025, with variation across industries and job roles. Surveys show many use AI for basic tasks like summaries or simple writing, while a few use it for more than a quarter of their daily work. Thus, the truly skilled group is much smaller than overall adoption numbers suggest.

This focus causes problems in management. Early in the PC era, many mid-career managers were simply less able to coordinate work using software than their younger staff. This caused tension in the workplace. The same thing seems to be happening again. Managers who aren't skilled with AI must either give way to younger, AI-expert employees or add inefficient layers of checking. Some firms are already reporting disagreements between tech-savvy teams and slower approvers, which are slowing down the gains that AI promises. Crucially, this isn't just a skills or training issue, but also an issue of bargaining power. Skill provides negotiation power, such as who gets to set agendas, who is given important tasks, and who gets promoted. If we don't take action, the skill gap will become an inequality that reflects and widens existing social divides.

What must educators, employers, and leaders do to close the AI skill gap?

Leaders and educators should treat AI skills like basic reading and writing skills. It's not just something nice to have; it's a core skill for everyone. This requires three related steps. First, schools must shift their programs from occasional coding courses to teaching how to frame problems, evaluate models, and make ethical judgments across every subject. Second, employers must create ways to reward skills with AI, such as short certifications, task switching, and group projects that connect beginners with skilled mentors. Third, government policy must help people in poorer communities access low-cost tools and mentorship, so that adoption doesn't depend solely on where one works or lives.

Each of these steps will face resistance. Some will say that changing the curriculum too quickly will weaken basic knowledge, or that schools can't keep up with changing tools. Others will worry about increasing surveillance if firms connect pay raises to narrow AI use numbers. These are valid concerns. The correct response is to design things sensibly and teach lasting thinking skills (such as problem-solving, checking sources, and causal reasoning) while providing brief training on current tools. Employers should avoid strict usage quotas and instead measure results, such as accuracy, speed, and quality improvements, which show serious tool use without causing mindless reliance. Public help should focus on mentorship and learning-by-doing, not just on giving out hardware. Evidence from workplace projects suggests that guided, project-based learning yields greater, longer-lasting gains than simple online courses.

Clear and testable steps for schools are simple. Start with the teacher's skill. Fund regional hub-teacher programs that give teachers ongoing practice time with AI models and funding for designing programs together. Add short AI sections into existing subjects. For example, history students can learn to check AI claims, biology students can test model-created experimental designs, and literature students can edit model drafts. For employers, create internal programs that rotate high-potential staff through AI-skill roles, connecting them with product and process teams. For leaders, fund regional simulation labs where small firms and adult learners can access toolkits and mentorship. These actions aren't costly compared to the economic risk of a divided job market; they are investments in resilience.

When faced with budget and political questions about spending public money on what appears to be company skill-building, we must answer them directly. When a new, general technology rewrites how work is done, public systems that support movement must adapt. There's historical evidence for this. Public investment in job training during earlier industrial changes reduced disruption and ensured that new industries remained available to everyone. The other option is skill monopolies controlled by private companies. A few employers would hold the keys to skill, and with them, greater hiring, pay, and leadership power. Public action protects choice and competition.

Changing the focus: policy for increasing improvement, not one-off training

The policy talk must shift from training many as a one-time response to building systems that prevent increasing inequality. Short training courses are helpful, but not enough if skill increases through networks, project selection, and promotion. We need policies that intentionally level the playing field, as current policies increase advantage. This means changing hiring practices, promoting from proven project results rather than background, funding mid-career moves to avoid skill lock-in, and encouraging open collections of prompts, rating guides, and program parts so that good practices spread rather than staying within institutions.

Workplace rules matter here, too, as much as training. Collective bargaining and professional certifications can set minimum expectations for access and fair assessment of AI-assisted work. Firms that connect compensation and advancement to AI-enabled numbers should provide clear guides and ways to improve. This is a governance challenge where rules can help. Transparency rules for buying AI tools and equal funding for public-sector training create a base level below which skills can't be monopolized by those already privileged.

We must also be realistic about speed. Some market watchers believe that the AI-PC change will slow after an initial business rush tied to hardware upgrades. This slowing down is real; hardware cycles matter, but it doesn't diminish the need to build AI skills. Even if device adoption slows, AI running in the cloud and hybrid workflows will keep skills in demand, helping people gain influence and higher pay. The time to act is short because once career paths and promotion practices shift toward AI skills, reversing course will be difficult and controversial.

In short, skill is not just about access to tools. It's about where the work goes, who puts it together, and who gets noticed in organizations. Policies designed only to buy devices or pay for general courses will not be enough. The right approach connects accessible tools with mentorship, project-based learning, and rules that prevent a small group from locking in too much advantage.

We end as we began. The new digital divide is the AI skill gap. One in six users today doesn't mean fairness later. It likely means small groups of highly skilled people who shape promotions, projects, and economic opportunities. The lesson from the PC era was not that technology replaces everyone uniformly, but that advantage accrues when early users turn innovation into an everyday benefit. We can let that turn into deep inequality, or we can create a different path. A path with programs that teach lasting judgment alongside prompts, workplaces that reward results instead of clicks, and public funding that buys mentorship and access, not just hardware. The risks are distributional and democratic. Skill must be treated as public infrastructure.

Act now. Fund teacher-hub projects, require workplace transparency for AI metrics, and create regional simulation labs for adult learning. If we treat skill like a public skill rather than a private benefit, we can guide the coming changes toward shared growth rather than narrow capture. The alternative is a job market where the skilled live in a different economy, one that is faster, richer, and less accountable, while everyone else struggles.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

EY. (2025). Work Reimagined Survey 2025: Companies missing up to 40% of AI productivity gains due to talent strategy gaps. EY Global.

Futurum Group. (2025). Don’t expect an acceleration in the rate of AI PC adoption in 2026. Futurum Group press release, Dec 10, 2025.

McKinsey & Company. (2024). The state of AI in early 2024: Gen AI adoption and business impact. McKinsey Global Survey.

Microsoft AI Economy Institute. (2026). Global AI Adoption in 2025 — A Widening Digital Divide (AI Diffusion Report 2025). Microsoft Research / AI Economy Institute.

European Commission, Joint Research Centre. (2025). Impact of digitalisation: 30% of EU workers use AI. JRC news release, Oct 21, 2025.

Comment