Integrating Physical AI Platforms into Education: A Forward-Thinking Policy Approach

Published

Modified

Physical AI moves intelligence from screens into systems that act in the real world In education, AI shifts from a tool to shared infrastructure with new governance risks The policy challenge is managing embodied intelligence at institutional scale

Automation is changing the world quickly. For example, factories added 4.28 million robots by 2023, a 10% increase in just one year. Now, intelligence is moving from distant data centers into machines that interact directly with the physical world. This shift means education policy must adapt quickly, as integrated systems combining software, sensors, processing, and mechanical components are becoming the norm. The main challenge is ensuring schools understand and address the mix of hardware, local processing, safety, and workforce changes as AI becomes both a physical and a digital force.

As AI moves from digital tools to physical devices, schools need a new way to bring technology into classrooms.

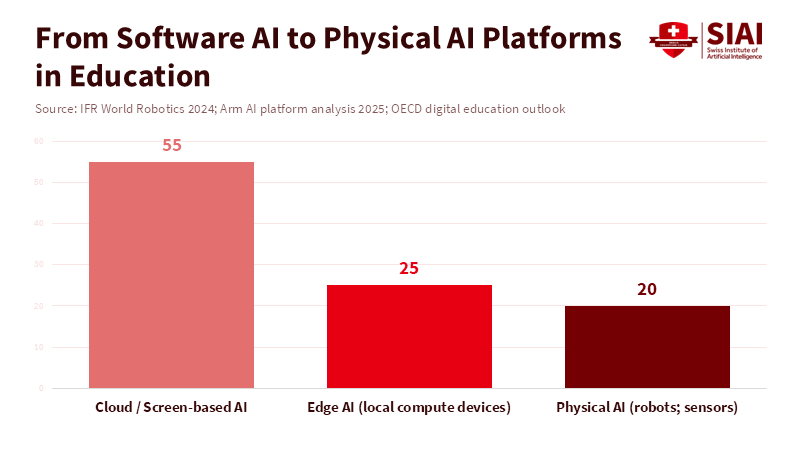

We need to change our approach. In the past, most discussions of AI in schools focused on software applications, such as content moderation, plagiarism detection, and personalized learning. These are still important, but now we should see software, hardware, and mechanical parts as components of a single system. This matters because spending, risks, and opportunities now overlap in the buying and use of these tools. When a school district buys an adaptive learning program, it’s not just a software license—they also deal with data sent to the cloud, on-site hardware, warranties, and safety steps for devices that can move, talk, or sense their surroundings. These changes affect budgets, teacher training, and fairness. Hardware depreciates differently from software, so maintenance costs are important but often overlooked. If schools treat these areas separately, they may misjudge costs and risks.

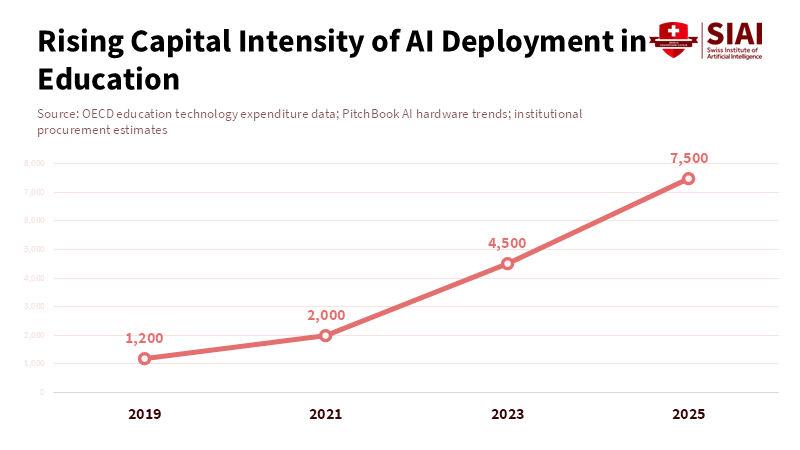

The numbers show strong growth. In 2023, there were about 4.28 million industrial robots in use, with more than half a million new ones added each year. This shows that physical systems are becoming common in many industries. The market for local AI processing is also growing fast and could reach tens of billions of dollars by 2024 or 2025. Venture funding for robotics and hardware-based AI has bounced back from 2022–2023, now reaching billions of dollars each year, mostly going to startups that blend on-device analytics with autonomous features.

Implications for Learning Environments and Curriculum Development

Moving to physical AI platforms changes what schools need to teach and maintain. Hardware skills are now essential. Teachers will need to manage devices that interact with students and classrooms, such as voice-activated tools, delivery robots, and environmental sensors. Buying teams must check warranties, update policies, and handle vendor relationships. Facilities staff should plan for charging stations, storage, and safety areas. Special education teams need to update support plans for new robotic tools that help with movement or sensory needs. Costs also need a fresh look. While software can be used by many, hardware incurs upfront costs, depreciates over time, and requires regular upkeep. Over five years, the total cost of classroom devices could exceed that of software if schools don’t plan for group purchases, shared services, or local repair centers.

AI devices can take over repetitive or routine tasks, letting teachers focus on students and advanced topics. Virtual assistants help with scheduling, grading, and paperwork. However, these benefits require reliable support and maintenance, or pilot programs risk failing. Policies should connect device funding to technical training and regular performance reviews.

Governance, Safety, and Workforce Policies for Physical AI Platforms

Bringing physical AI into schools creates new challenges for rules and oversight. Physical systems can fail in different ways, such as sensor errors, mechanical breakdowns, or poor decisions. Rules designed for software problems are not enough for robots capable of causing real-world harm. Regulators need to set up standard safety checks that test software, stress-test hardware, and look at how people use the systems. These checks should compare different systems directly. For privacy, processing data on-site means less student data goes to the cloud, but it also brings up concerns about data logs, device software, and data sent to vendors. Policies should limit what is recorded on devices, clarify data handling, and require regular external audits.

Policymakers also need to focus on workforce development. There will be more need for maintenance workers, safety staff, and curriculum experts who understand both technology and society. Fair access is still key. Without action, gaps in access and support could reduce the benefits of new technology. Policymakers should back shared service centers for repairs and support, use funding that combines startup grants with ongoing payments, and require clear training and worker protection rules.

Evidence-Based Evaluation, Addressing Concerns, and Moving Forward

Concerns persist about past hardware projects—overhyped pilots, costly or unused devices, and incompatibility persist if support is lacking. The key is structured pilots and honest evaluation. Schools should track system uptime, learning time saved, support hours, and student outcomes, reporting findings publicly. Some believe hardware-based AI can help underserved schools automate hard-to-staff services, depending on funding. Shared services and vendor accountability may improve equity; if not, gaps may grow.

To lower risks and maximize benefits, policymakers should emphasize four clear policy actions: First, require industry-wide interoperability standards and enforceable warranties, ensuring schools can repair and maintain devices from multiple providers. Second, create and support regional service centers dedicated to device maintenance, software updates, and independent safety checks for school systems. Third, make successful implementation depend on teacher-led training and curriculum integration, rather than on simple device delivery. Fourth, mandate transparent public reporting on system uptime, safety incidents, and learning outcomes for any AI products used in schools. These steps will enable evidence-based decisions and prevent investments driven by novelty rather than impact.

In conclusion, intelligence is evolving beyond software. The increase in autonomous agents and robots puts physical AI at the forefront of decisions about education policy. Policies that view software, local processing, and physical elements as different purchases risk inefficiency and waste. Policymakers should adopt an integrated system that coordinates purchase, maintenance, safety, and educational methods. We need defined standards, institutions that support maintenance, and funding plans that sustain operations. When done right, schools will gain tools that increase human potential. When ignored, educational technology will be unequal. By making the platform last, the potential of physical intelligence can lead to public good.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Arm. (2026). The next platform shift: Physical and edge AI, powered by Arm. Arm Newsroom.

Crunchbase News. (2024). Robotics funding remains robust as startups seek to… Crunchbase News.

Grand View Research. (2025). Edge AI market size, share & trends. Grand View Research Report.

IFR — International Federation of Robotics. (2024). World Robotics 2024: Executive summary and press release. Frankfurt: IFR.

PitchBook. (2025). The AI boom is breathing new life into robotics startups. PitchBook Research.

TechTarget. (2024). What is AgentGPT? Definition and overview. TechTarget SearchEnterpriseAI.

The Verge. (2026). AI moves into the real world as companion robots and pets. The Verge.

Comment