Cool Water, Hot Compute: Why Data Center Water Cooling Must Shape Education Policy

Published

Modified

AI in education needs compute; cooling drives water, power, and trust costs Require verified standards for data center water cooling, power, and heat reuse Site compute in low-water regions and reuse heat to scale AI responsibly

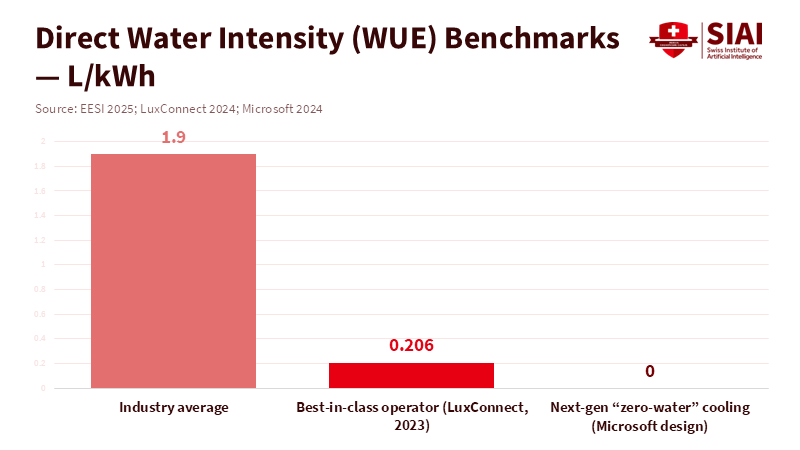

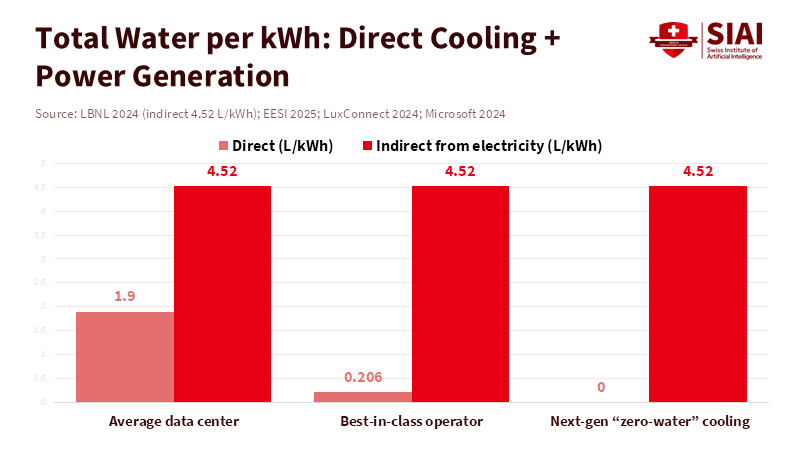

Operating a 100-megawatt AI campus for a year uses substantial water. The industry average for direct water use is about 1.9 liters per kWh, so cooling alone could take about 1.66 billion liters. Including the indirect water used to generate electricity—about 4.5 liters per kWh on a U.S. grid—the total exceeds 5 billion liters. This is a very important issue for communities and schools. Artificial Intelligence tutoring, learning analysis, and campus research all depend on computer power housed in data centers. How these data centers cool their systems determines if these benefits can grow without using up local water or causing power and heat problems for schools and cities. The choice is not between stopping new ideas and holding back, but between uncontrolled growth and planned growth. Education leaders can make rules for the systems they use more and more.

Data Center Water Cooling is Now an Education Issue

Education is quickly changing to Artificial Intelligence services. This change depends on a large increase in electricity use by data centers, which could double in a few years. Power usage has improved in some areas, but reducing electricity use does not eliminate heat. It only moves the problem to cooling. In hot, dry areas, many companies still use systems that evaporate water to save electricity, but this uses a lot of water. In cooler or wetter areas, they use chillers or liquid cooling to use less water, but these can use more power. School systems are stuck between two problems: higher power bills for services they now need, and political problems when a new computing center comes to town and uses a lot of water for data center cooling without telling people.

The other problem is trust. People in the community need to know how much water each facility uses directly and how much is used to generate power for the campus. Most companies do not clearly report both of these things, and even fewer promise to stay within a specific limit per unit of computer power. For schools, this means they are taking risks without control. Teachers want fast Artificial Intelligence tools, technology leaders want reliability, and facility teams want bills they can estimate. But the cooling methods and power sources behind these services are often kept secret. This gap will raise costs in the future. It also makes schools look bad if using Artificial Intelligence seems to be taking water away from the community.

Design Rules: Data Center Water Cooling Without Local Harm

Education buyers can change things. They can make data center water cooling a key thing they ask about in every computer contract. They can set a water-use limit that decreases each year, and the limit is audited by an independent auditor. They can push to use 0.4 liters of water per kWh or less by the end of the decade, since some places are already close to zero water use. They can make companies share a water total that includes both direct cooling water and water used to generate electricity. This number should be easy to compare between different offers. They can also set a power-use limit near 1.1 to keep heat loss low. These two numbers—water use and power use—give schools a simple way to compare offers without getting lost in marketing.

Rules should go with buying. State education groups can create a computer budget rule: every new Artificial Intelligence program that uses the cloud must present a simple water-and-power plan. The plan should name the area where the data center is, the data center's cooling method, the expected water and power use, and how much of the energy is carbon-free, all day, every day. They can connect grant money to real-time reporting. They can make public dashboards so parents, teachers, and local leaders can see how much water and power are used each week for every thousand student actions. There is a give-and-take between electricity and water in cooling choices, but that should be clear. Once the numbers are easy to see, leaders can pick locations and sellers that fit local needs.

Turning Heat to Learning: District Heating and Campus Wins

Computers make heat. When captured, that heat can warm homes, labs, and gyms. Some projects are showing how to do this on a big scale. Large projects in Nordic countries and Ireland take waste heat from server rooms, improve it with heat pumps, and send it to city networks. Universities are a good fit because they are near areas that need steady, low-temperature heat. They also control roofs, basements, and pipes where exchangers and pumps can be put. For a public university, a data center cooling plan that includes heat recovery is not just a bonus—it's a way to protect itself. It reduces winter gas use, keeps operating costs steady, and turns a negative into a positive for the public.

The design goal is simple: no wasted heat. Education buyers should ask in every cloud or colocation deal where the heat will go and who will benefit. If the facility is connected to district heating, it requires a signed agreement and a minimum annual heat delivery. If there is no network, ask for ways to use the heat on-site—such as hot water for dorms, pool heating, or greenhouse projects that support agriculture programs. Funding groups can prioritize grants that connect Artificial Intelligence programs to heat reuse. The costs are getting better as liquid cooling becomes more common. Liquid systems make it easier to capture heat at useful temperatures, reducing the size and cost of heat pumps. Schools can take charge by stating that the data center cooling plan includes a heat-recovery plan, not just a score for how well it performs.

From Mountains to the Sea: Data Center Water Cooling Beyond the City

Locations are changing. Some companies are moving computer operations to cooler mountain areas, where cold temperatures and cave-like tunnels lower cooling needs. Others are trying underwater modules that use the stable ocean conditions to remove heat without using freshwater. Another idea is still new but important: data centers in orbit that would use constant sunlight for power and the cold of space for cooling. None of these ideas is perfect. But they make the map bigger. For education, the lesson is clear. We should not assume that fast Artificial Intelligence must be close to the city. We should buy services that fit our climate and community needs, including the data center water cooling effects we are willing to accept.

These ideas do have trade-offs. Mountain tunnels and cool areas lower fan use and water needs, but they can be far from fiber networks, which adds network costs and delay. Underwater units avoid using freshwater and have proven reliable, but they face challenges with maintenance, permits, and seabed use. Space ideas promise clean power and easy heat removal, but launch pollution and space-junk risks must be reduced for them to help the climate. The policy for schools is not to pick one idea. It is to set goals. Ask sellers to meet strict water and power limits for each unit of computer power, and let them meet those limits with the mix of location and technology that works. If a company can meet the data center cooling standard under the sea, on a plateau, or in a park near a city heat network, that is their choice.

What Educators Should Do Next

Start with contracts. Every Artificial Intelligence tool used by schools should point to a computer center that meets public data center cooling and power standards. If a seller cannot show a water and power use number that can be checked, move on. Next, plan for the location. For tasks that can handle some delay—tests, model practices, data analysis—choose cooler, water-safe areas. For classroom tools that need to be fast, prefer locations that reuse heat into community networks. Then, connect payments to results. Make it cheaper for sellers to meet your standards than to avoid them. Offer long-term deals to providers that hit low-water and power-use levels and send heat into public or campus systems. Connect education technology renewal to lower use numbers each year. Share the results.

Build knowledge within your team. Train staff to understand water and power terms in data center contracts. Include in teacher and student training the link between Artificial Intelligence and these physical systems. Clearly define the key numbers: liters per kWh, watts per unit of compute, and megawatt-hours of heat reused. By making these numbers common knowledge, demand will drive the market toward better practices.

The first number is worth saying again. A year of computer use at a big Artificial Intelligence site can use billions of liters of water when you count both direct cooling and the water used for its power. That is not a reason to stop learning or researching. It is a reason to guide it. Schools are big buyers of digital services. They can require data center cooling that uses water, provides clean power, and recycles heat. They can pick locations that fit local water and energy limits. They can ask for clear information and turn down deals that hide the basics. If we want Artificial Intelligence in every class, we must count every liter and every kilowatt. The future we teach should be the one we make. Let education lead by setting the rules for the computer power it uses.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aquatherm. (2025). Using waste heat from data centres: Turning digital heat into community warmth.

Fortum. (2024). Microsoft X Fortum: Energy unites businesses and societies.

Google. (2024). Power Usage Effectiveness.

International Energy Agency. (2024). Electricity 2024—Executive summary.

International Energy Agency. (2024). Energy and AI—Energy demand from AI.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Shehabi, A.). (2024). United States Data Center Energy Usage Report.

LuxConnect. (2024). Water efficiency in the data center industry.

Meta. (2020). Denmark data center to warm local community.

Microsoft. (2024). Sustainable by design: Next-generation datacenters consume zero water for cooling.

Microsoft. (2020). Project Natick: Underwater datacenters are reliable and conserve freshwater.

Ramboll. (2024). Meta surplus heat to district heating.

SEAI. (2023). Case study: Tallaght District Heating Scheme.

Thales Alenia Space / ASCEND. (2024). Feasibility results on space data centers.

UN Environment Programme—U4E. (2025). Sustainable procurement guidelines for data centres and servers.

U.S. Department of Energy. (2024). Best practices guide for energy-efficient data center design.

U.S. Environmental and Energy Study Institute. (2025). Data centers and water consumption.

eGuizhou. (2024). How Guizhou’s computing power will drive fresh growth.

China Daily. (2023). Tencent’s mountain-style data center in Gui’an.

World Economic Forum. (2020). Project Natick overview.

Reuters. (2025). Nordics’ efficient energy infrastructure ideal for Microsoft’s data centre expansion.

Comment