The Two-Speed Reality of Classroom AI

Published

Modified

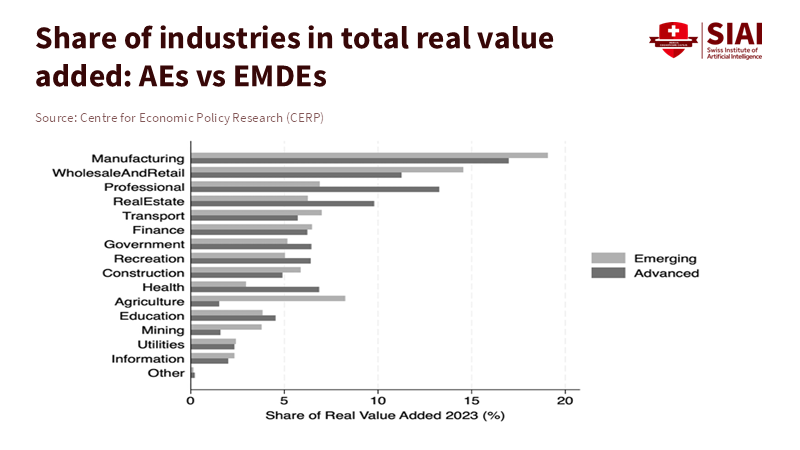

Generative AI lifts advanced economies faster due to compute, connectivity, and wages Education faces a widening generative AI productivity gap without solid infrastructure Front-load broadband and compute, standardize platforms, and train teachers to close it

North America accounts for nearly half of the world’s live data-center capacity, yet approximately three billion people remained offline in 2023. This disparity is not merely an abstract digital divide; it establishes the foundation for a generative AI productivity gap that will shape educational institutions and workforce development over the next decade. Recent analysis from the Bank for International Settlements indicates that generative AI is likely to increase output more significantly in advanced economies than in emerging ones. This outcome is driven by the availability of advanced resources such as computing power, connectivity, and higher wages, which make automation more economically viable. As of 2024, only about 14% of firms in the OECD had adopted AI, with leading organizations advancing while others lag behind. Consequently, the most substantial benefits from classroom AI tools will initially accrue to educational systems capable of investing in robust cloud services, low energy costs, and specialized expertise. Addressing this gap now requires policy intervention alongside technological solutions.

Defining the generative AI productivity gap

We need to clearly define the problem. The generative AI productivity gap is the difference between what AI can achieve in education and what schools can actually implement after accounting for infrastructure and workforce costs. Macro data makes this gap clear. The BIS finds that, on average, generative AI’s short-term growth impact is greater in advanced economies than in emerging ones. This trend is consistent with broader patterns: although AI adoption among OECD firms has approximately doubled in recent years, overall uptake remains low, with leading organizations advancing more rapidly. In the educational context, only well-funded districts and universities are likely to adopt advanced teaching assistants, AI-graded assessments, and automated student support processes in the near term. Other institutions may be limited to basic solutions, such as chatbots that lack full integration, do not connect to secure data, and are vulnerable to network disruptions. The limited solutions, like chatbots that lack full integration, do not connect to secure data and struggle when network issues arise.

The gap also relates to larger economic factors. Generative AI impacts productivity by automating certain tasks, improving tools, and shifting capital. Preliminary models from the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) suggest that AI could enhance productivity and GDP growth over the coming decades, with noticeable budgetary effects as early as soon. EY found that business investment in AI-related areas such as software, data centers, and energy infrastructure increased at an annual rate of nearly 18% in early 2025, contributing roughly 1 percentage point to quarterly U.S. GDP growth. However, these investments are not evenly distributed. Cloud spending tends to be concentrated, with major markets capturing most of the migration, optimization efforts, and GPU capacity. In education, this translates to a clear pattern: districts and universities that can afford usage-based cloud services, reserve capacity in data-center regions, and recruit AI-savvy leaders will realize expected learning improvements. Others will face higher costs and slower feedback.

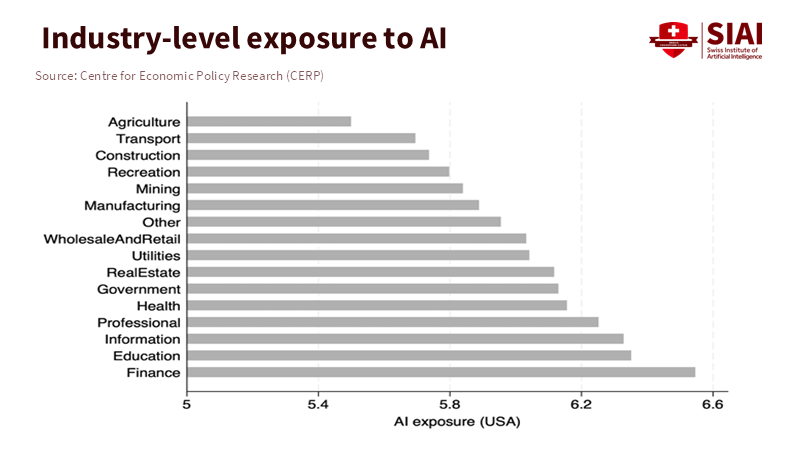

Channels of impact behind the generative AI productivity gap

AI transforms three primary dimensions: the tasks performed by individuals, the capabilities of software, and the allocation of financial resources. Regarding tasks, AI can assist in creating lesson plans, developing assessment options, summarizing feedback, and generating personalized practice materials across various educational roles. However, the productivity gains depend on how time is allocated within these systems. Educational systems with higher teacher salaries and constrained staffing benefit more, as saved hours can reduce budget pressures or enable smaller class sizes. In contrast, systems with lower wages experience smaller savings and have less incentive to modify schedules. Thus, labor market dynamics are a significant factor. On a broader scale, persistent service-sector inflation and wage trends in advanced economies have kept labor costs high relative to pre-pandemic levels, making AI-driven automation and support more attractive in these regions. The benefits increase as institutional leaders implement these changes.

Next, tools improve usability. PWBM notes that AI boosts productivity by enhancing the efficiency of complementary software and hardware. In education, this means better content platforms, learning analytics, and automated workflows that integrate with student information systems. However, these tools rely on stable internet connections, strong identity and access controls, and data-sharing agreements. The global picture is mixed here. The World Bank reports that around 63% of the global population used the internet in 2024. The ITU shows progress in mobile broadband affordability, but fixed broadband—which is crucial for schools streaming video and conducting data analysis—remains expensive in many areas. Where bandwidth is unreliable, AI features may be limited or shut off. This leads to a two-tier adoption pattern: one for high-capacity systems where everything functions well, and another for those where AI functions as a thin layer over fragile networks.

Finally, capital flows to areas where it is most needed. Generative AI requires significant computing power. Data from data centers shows decreasing vacancy rates in key locations, with rapid construction constrained by energy access. Knight Frank notes that North America accounts for almost half of global live IT capacity, while new supply in some parts of Asia lags. Gartner predicts that public cloud spending will exceed $700 billion in 2025, with much of that growth driven by AI demand. This concentration matters for schools and universities. If a region is far from a cloud center, latency increases, expenses rise, and access to specialized services becomes limited. While pricing is global, service availability is local. These structural issues favor advanced economies with dense cloud infrastructures, reliable energy connections, and experienced procurement teams.

Why advanced economies pull ahead

The BIS findings offer a broad overview, but the real details emerge at the ground level. Start with computing power. AI training relies on specialized chips and strong equipment. Supply is limited and concentrated. The World Bank report says Nvidia holds a large share of the data-center GPU market. Export controls and industrial policies affect where top chips go. Recent shifts have moved high-end GPUs to places with fewer policy issues and better energy access. Educational systems in these areas can use advanced applications and process sensitive data offline. Others must manage with limited or delayed access. This is not just about talent. Infrastructure and policy play a significant role.

Next, let’s look at connectivity. Despite improvements, billions of people are still offline, and many schools rely on fixed broadband that still doesn't meet affordability goals. A system cannot offer uninterrupted tutoring if the network is unreliable. It also cannot send analytics to teachers for every class if uploads fail. Mobile connectivity is improving, but fixed lines remain essential for high-volume teaching and district operations. This is where the reality of the generative AI productivity gap widens. A school in a major city might use intelligent scheduling and AI-assisted individual education plans as the norm, while a rural district might restrict their use to exam periods. The same software can yield vastly different outcomes.

Labor costs further widen the gap. In advanced economies, growth in service-sector wages has remained high enough to enable rapid gains from AI adoption and support. An office that automates document handling, or a university that uses AI for student services, can free skilled workers to handle more complex tasks. The resulting savings can be realized within a year, encouraging further investment and process improvements. In low-wage areas, leaders see fewer short-term financial benefits and tend to operate under rigid roles with limited IT budgets. They may hesitate to adjust schedules and workflows, slowing the compounding effects that lead to real AI productivity gains. The paradox is that wealthier schools are also quicker to invest in AI-ready systems, thereby reducing their costs of further adoption.

Market structure contributes as well. Public cloud spending is heaviest in the United States and Europe. There, universities and educational technology firms can commit to multi-year contracts and standardize on cloud-native systems. Vendors prioritize features based on customer size and compliance needs. Evidence from the OECD shows that early adopters lead the way, with divisions forming along traditional lines such as firm size and sector. In education, this results in a divide between top-tier universities and underfunded colleges, as well as between urban districts with dedicated technology leaders and rural districts with part-time IT support. The outcome is an uneven distribution of benefits: a few systems gain a lot, while most gain little. This pattern aligns with the BIS’s near-term predictions: generative AI increases productivity, but the early benefits are more pronounced in advanced economies with better infrastructure and higher wages.

Policy to narrow the generative AI productivity gap

The objective of this policy is not to impede progress among leading institutions, but rather to accelerate the adoption of comprehensive AI solutions by those currently lagging. The first policy lever involves improving access to computing resources. Ministries and state agencies should establish regional education compute pools that guarantee GPU hours for public schools and teacher colleges. While cloud credits can facilitate this, the critical factor is enforcing service levels, including reserved capacity in proximate regions, low-latency connections, and stable pricing for workloads that require substantial processing during school hours. In areas with limited capacity, governments should coordinate AI rollouts with investments in data centers and power infrastructure. For this reason, data-center vacancy rates, power availability, and regional coverage must be integrated into education technology planning. Regulators should also streamline cross-border data flows for model fine-tuning on anonymized student data, ensuring robust protections. Absent these measures, classroom AI pilots will encounter significant challenges during peak periods such as examinations.

The second lever is ensuring connectivity where it's most needed. Data from the ITU and World Bank show steady improvements, but gaps remain in fixed-line access. Education funds should focus on building reliable campus networks, last-mile fiber connections, and affordable programs specific to schools that aim for fixed-line access, not just mobile packages. In cases where fiber is unrealistic, hybrid models should be planned. This could include local inference boxes for essential tasks, scheduled synchronization windows, and cached content. The goal is to keep key AI functions operational throughout the day, even with weak internet connections. Broadband is no longer just a support service; it's a critical part of learning. This perspective can help reclassify network upgrades as instructional spending, opening up new funding channels and donor support.

The third lever is procurement and capability development. The evidence from the OECD is clear: leaders make progress by standardizing, measuring, and improving. Education systems should adopt similar practices. They should buy complete platforms instead of piecemeal solutions. Require vendors to provide APIs for student information systems, assessment engines, and learning management systems. This way, AI features won’t exist as isolated trials. Contracts should be tied to meaningful outcome metrics, such as time saved for lesson preparation, earlier identification of dropout risks, and improvements in student writing assessed with consistent rubrics. Then, the results should be published. When districts can witness credible, comparable improvements, others will follow. This method allows a small group of leaders to move the entire system forward rather than extend the laggards' time.

Finally, it's essential to realign labor incentives. Advanced economies benefit in the short term because the wage structure makes calculations straightforward. Emerging systems can still succeed by directing AI towards specialized expertise rather than economical replacements. Focus on applications that maximize expert time: speech therapy triage, early-warning systems for at-risk students, and personalized support modules in the first year of university. These uses do not rely solely on wage differences. They need high-quality data, practical teacher training, and strong governance. If ministries invest in training-focused deployments—where teachers receive time off, coaching, and opportunities for community practice—the returns improve even if salaries are low. This strategy builds human capital for AI and is not just a cost-cutting effort with education in its title.

Addressing potential critiques, some might argue that open-source models and cheaper chips will level the playing field. While it's true that costs will decrease and access will widen, the immediate situation remains sticky. Data center growth is limited by power constraints in existing hubs, and establishing new regions takes time. Public cloud spending is still concentrated in markets with high enterprise demand. Even if a model license is free, running large-scale inference necessitates stable networks and employed engineers. The BIS findings reflect a short-term outlook. In this short period, the limitations are practical, financial, and institutional. The solution is not to give up; instead, we should create the necessary infrastructure now so that when costs drop, schools can take full advantage quickly.

What educators can do next. University leaders should align their programs with AI channels that actually boost productivity: time saved on routine tasks, higher-quality feedback, and earlier student support. They should implement six-week sprints to redesign one course or service from start to finish using AI, then ensure the gains are secured. District superintendents should collaborate to pool demand to get reserved cloud capacity and fixed-line upgrades. They should also require service-level credits when latency affects teaching. Teacher training programs need to incorporate AI-assisted planning and assessment into practical experience, making it a requirement rather than an elective with supervision and documentation. All of this should be based on reliable measurements rather than flashy demonstrations. We should reward teams that turn AI into lasting changes in schedules, rather than focusing solely on those who run the most impressive pilot projects.

What policymakers must decide. Ministries should view the generative AI productivity gap as a new equity issue that requires the use of old tools: targeted investment, transparent benchmarks, and shared services. They should publish a national infrastructure map for AI in education that outlines compute regions, fiber reach, school network readiness, and teacher training capacity. Grants should be tied to improvements on this map. Ministers should negotiate regional education cloud cooperation across borders where single countries are too small to attract vendors. Budget considerations must remain a priority: early estimates from PWBM indicate that national accounts will see genuine but modest fiscal effects soon. Hence, the education sector cannot wait for a growth dividend to fund infrastructure. They must invest upfront and capture savings in later years as workflows stabilize.

The outcome to aim for. We will know the gap is closing when three things occur simultaneously. First, schools in secondary cities can conduct reliable AI-assisted instruction all day without bandwidth rationing. Second, the reallocation of teacher time is reflected in schedules, not just in surveys, and attrition drops when AI reduces tedious tasks. Third, vendors can deliver their best features to more languages and regions simultaneously because demand is correctly pooled and service levels are enforced. These are tangible indicators, not just slogans. They suggest a path where emerging systems can benefit more before wages rise or local chip manufacturing comes into play.

Convert a structural head start into shared benefits

The available evidence strongly supports the need for immediate policy action. Analysis from the Bank for International Settlements indicates that the initial benefits of generative AI will accrue primarily to advanced economies, while OECD data confirms that leading institutions are progressing more rapidly. Disparities in cloud services, computing power, and wage structures contribute to this unequal landscape. However, these outcomes are not inevitable. Reports demonstrate that the gap can be narrowed through targeted investment in AI-supportive infrastructure, improved affordability, and collaborative public sector purchasing. Education leaders should prioritize reserving computing resources, ensuring service levels, establishing reliable fixed-line connections, and procuring platforms that offer data visibility and measurable outcomes. Teacher training should be integrated into regular work schedules. Although these measures may lack immediate appeal, they are essential for converting AI’s potential into tangible productivity gains for students. Achieving these objectives will transform the generative AI productivity gap from a significant global challenge into a manageable local issue, enabling disadvantaged systems to realize substantial future gains.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Artificial intelligence and growth in advanced and emerging economies: short-run impact (BIS Working Paper No. 1321).

CBRE (2025). Global Data Center Trends 2025.

EY (2025). AI-powered growth: GenAI spurs US economic performance.

Gartner (2024). Worldwide Public Cloud End-User Spending Forecast, 2025.

International Monetary Fund (2024). World Economic Outlook, October 2024, Chapter 1.

International Telecommunication Union (2025). Affordability of ICT Services 2025.

Knight Frank (2025). Global Data Centres Report 2025.

OECD (2024). Fostering an Inclusive Digital Transformation as AI Spreads among Firms.

OECD (2025). AI Adoption by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises.

Penn Wharton Budget Model (2025). The Projected Impact of Generative AI on Future Productivity Growth.

World Bank (2025). Digital Progress and Trends Report 2025.

World Bank (2024). Digital Connectivity Scorecard.

Comment