The Orbit Option: Orbital Data Centers and the New Economics of Learning

Published

Modified

Orbital data centers could ease power and cooling limits on Earth The costs and climate trade-offs are still unclear Education should set rules now before orbit becomes a new dependency

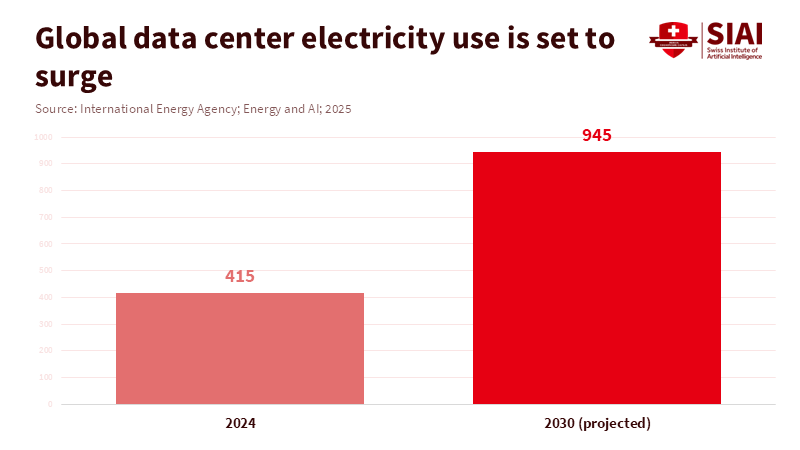

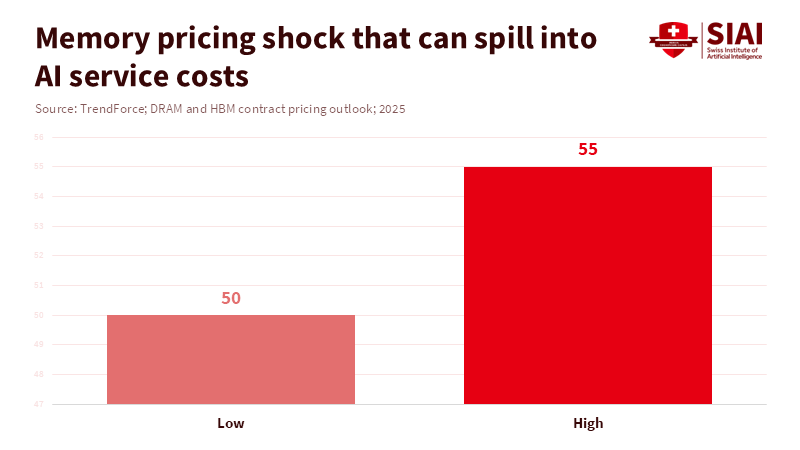

Global data centers consumed roughly 415 TWh of electricity in 2024, accounting for 1.5% of global electricity use. Schools are now encouraged to leverage AI tools for instruction, writing support, and administration. These cloud-based tools rely on electricity, cooling, and processing chips, driving operational costs. High electricity prices and grid constraints threaten educational budgets. Memory prices are another pressure point, as TrendForce predicts DRAM and HBM contract pricing could climb 50–55% between 2025 quarters. Amid such trends, exploring off-planet AI infrastructure for education as a cost-saving solution is timely.

The standard approach involves expanding ground-based data centers and transitioning to cleaner energy, but educational institutions face location, permitting, grid, and water issues. Orbital data centers offer clear benefits: consistent solar energy, efficient heat dissipation, and relief from land, water, and local political constraints. Although launch costs and space operations are complex, these centers could improve access to AI, reduce costs, and increase control over education.

Orbital data centers and the energy bottleneck in education AI

Electricity is a key factor in digital learning. The IEA estimates that data center electricity demand could double by 2030, reaching roughly 945 TWh. In the U.S., the Department of Energy reports that data centers consumed about 4.4% of U.S. electricity in 2023, with a possible rise to 6.7%-12% by 2028. These figures are essential for education, as many institutions have climate targets, fixed budgets, and limited control over utility prices. When power is scarce, new connections can be delayed, or fees increased. This can slow data center growth and increase the cost of AI services for schools.

Cooling also turns on community sentiment. Pew reported that U.S. data centers directly used around 17 billion gallons of water in 2023. Even with reduced water use, public perception is relevant. Communities may question why data centers receive water during droughts while schools struggle with heat. Tech companies are responding with improved designs, such as waterless cooling systems. Microsoft introduced a data center design that uses zero water for cooling via chip-level cooling. This helps, but does not resolve the land and grid issues that affect the siting of new facilities.

Orbital data centers offer distinct advantages in cooling and electricity. In orbit, solar power is consistently available, enabling a steady energy supply, while waste heat is efficiently released into space, eliminating the need for large water-based cooling systems. These centers thus promise stable, water-independent operations and potential cost reductions. If space-based systems prove reliable, orbital data centers may relieve pressure on land and water resources. However, challenges remain, including launch availability, radio bandwidth limitations, and security.

Orbital data centers and the memory shock behind “cheap” AI

Education leaders may hear that AI costs will decline. While this can be true for software, the necessary hardware may not follow suit. The cost of AI is linked to memory and processing power. Modern AI needs substantial fast memory, relying on DRAM and HBM. TrendForce projects a possible 50–55% rise in total contract pricing, including DRAM and HBM, between quarters in late 2025. Demand for premium memory and higher prices for other consumers may impact the market (Financial Times, 2026). Schools may face higher device prices, and cloud providers may pass costs along as they update their systems for AI. Orbital data centers are a long-term investment that can reduce electricity and cooling expenses.

Orbital data centers will not immediately resolve memory constraints. Space equipment must withstand radiation to prevent errors. Space hardware needs radiation protection through shielding or error-correction software, and cooling components that add weight for launch (Hsu, 2025). But, on-site chip fabrication can happen in space. Space Forge created plasma on a satellite to enable in-orbit processes used in chip manufacturing. Microgravity and cleanliness can allow components to be more exact. Space Forge's goal is to produce crystal material that is purer than Earth-made versions.

Purer chips” highlights monetary movement. If space-based methods improve yields or enable new materials, areas like AI chips, sensors, and comms will be affected first. This can widen the gap between educational institutions that can afford superior processing power and those that cannot. Space data center construction notes that China has launched spacecraft for this purpose, and the EU is exploring similar approaches under ASCEND. Orbital data centers are a strategic asset. Because systems are strategic, accessibility is guided by politics, export policies, and security evaluations. Education systems that depend on AI services should consider this risk, as well as vendor lock-in.

The hard parts: launch costs, climate math, and who bears the risk

All orbital data center proposals face barriers related to the costs of placing equipment in orbit. Launch cost and periodic chip replacement affect investment. This turns orbital data centers into ongoing operations. A few things to think about when purchasing: who pays when equipment fails or needs to be pulled, and Google’s Suncatcher team estimates that liftoff costs must fall to under $200 per kilogram by 2035. Many economic gains depend on launch expenditure. Education policies cannot rely on future price drops or assume that early orbital processing will be affordable for public schools.

The climate case is also contested. Some claim that solar and water-free cooling could reduce carbon emissions relative to on-planet options, and Starcloud has stated this. However, “Dirty Bits in Low-Earth Orbit” suggests that launch and re-entry emissions mean that in-orbit processing could be more carbon-heavy than on-planet options. Thales Alenia Space stated that ASCEND predicted that space data centers need a launcher ten times less emissive to lower CO₂ enough. In addition to space debris and pollution, orbital data centers do not automatically mean climate wins. It's a negotiation, so the public should state the terms.

Education policy for an orbital data centers era

Should orbital data centers be established, a new reliance will be created. Education bandwidth, devices, staff time, spectrum, ground stations, locations, and regulations determine where data is processed. AI service contracts should be made visible. If a vendor model depends on memory supply or orbital capacity, schools need service guarantees. Public buying should ensure model behavior and data handling are checked, as off-planet systems can make oversight more difficult. As orbital data centers are being sold in the language of sovereignty, education, energy, telecom, and space, regulators should coordinate their efforts.

Curriculum policies also need to adapt as professions change. Orbital data centers use remote control, radiation-aware processing, fault tolerance, and space-asset cyber defense. Google's Suncatcher research highlights the effects of radiation and the need for inter-satellite bandwidth. Programs have to mix computer science, electrical engineering, aerospace systems, and public policy. Critics believe that schools are too far away from these items to make a difference. The prices of those projects are unlikely to be cut for the average education buyer in the coming years. Space computing is not what the system will bet on. Action must be taken before orbital data centers become popular. Policymakers should get space, energy, and learning on the same page so the next processing surge helps students first, not investors. In addition, researchers should test full-life emissions and safety claims before orbit becomes the norm for the digital learning sector.

In 2024, data centers worldwide needed hundreds of TWh to operate. Education comes after those data requests. If processing becomes a limited input to education, then the servers become a public policy issue. Orbital data centers address the land, water, and grid constraints that shape the cloud. They can also become constraints through launch slots, security protocols, and questionable climate data. Education leaders must view orbital data centers as an option and start writing the rules for accessibility today.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Beals, T. (2025, November 4). Exploring a space-based, scalable AI infrastructure system design. Google Research Blog.

Financial Times. (2026). Chip shortages threaten 20% rise in consumer electronics prices.

Hsu, J. (2025, December 9). Data centers in space aren’t as wild as they sound. Scientific American.

IEA. (2025). Energy and AI. International Energy Agency.

Microsoft. (2024). Sustainable by design: Next-generation datacenters consume zero water for cooling. Microsoft Cloud Blog.

Mogensen, J. F. (2025, December 31). The push to make semiconductors in space just took a serious leap forward. Scientific American.

NVIDIA. (2025). How Starcloud is bringing data centers to outer space. NVIDIA Blog.

Ohs, R., Stock, G. F., Schmidt, A., Fraire, J. A., & Hermanns, H. (2025). Dirty Bits in Low-Earth Orbit: The carbon footprint of launching computers. arXiv.

Pew Research Center. (2025). What we know about energy use at U.S. data centers amid the AI boom.

Thales Alenia Space. (2024). Thales Alenia Space reveals results of ASCEND feasibility study on space data centers. Thales Group.

Tom’s Hardware. (2026). UK company shoots a 1,000-degree furnace into space to study off-world chip manufacturing.

TrendForce. (2025). Global DRAM revenue jumps 30.9% in 3Q25; conventional DRAM contract prices forecast to rise. TrendForce Press Center.

U.S. Department of Energy. (2024). DOE releases new report evaluating increase in electricity demand from data centers.

Comment