Stop Chasing Androids: Why Real-World Robotics Needs Less Hype and More Science

Published

Modified

Humanoid robot limitations endure: touch, control, and power fail in the wild Hype beats reality; only narrow, structured tasks work Fund core research—tactile, compliant actuation, power—and use proven task robots

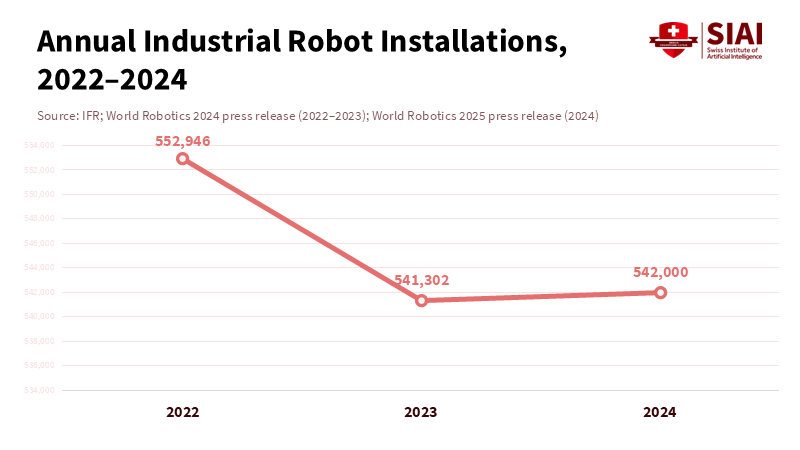

We don't have all-purpose robots because building them is more complicated than we thought. The world just keeps messing them up. Get this: about 4 million robots work in factories now—a record high!—but none of us see a humanoid robot fixing stuff around the house. Factory robots kill it with set tasks in controlled areas. Humanoids? Not so much when things get messy or unpredictable. That difference is a big clue. Sure, investors poured billions into humanoid startups in 2024 and 2025, and some companies were valued at insane levels. Reality check, though: dexterity, stamina, and safety are still big problems that haven't been solved. Instead of cool demos, we need to fund research into touch, control, and power. Otherwise, humanoids are stuck on stage.

Physics Is the First Problem for Humanoid Robots

Our bodies use about 700 muscles and receive constant feedback from sight, touch, and our own sense of position. Fancy humanoids brag about 27 degrees of freedom—which sounds cool for a machine, but it's nothing compared to us. It's not just about the number of parts. It's about how muscles and tendons stretch and adapt. And we sense way more than any robot. Even kids learn more, faster. A four-year-old has probably taken in 50 times more sensory info than those big language models, because they're constantly learning about the world hands-on. Simple: motors aren't muscles, and AI trained on text isn't the same as a body taught by the real world.

The limitations become evident when nuanced manipulation is required. Humanoid robots typically perform well on demonstration floors, but residential and workplace environments introduce variables. Friction may vary, lighting conditions can shift, and soft materials create obstacles. A robotic hand incapable of detecting subtle slips or vibrations will likely fail to retain objects. While simulation is beneficial, real-world deployment exposes compounding errors. Industry proponents acknowledge that current robots lack the sensorimotor skills that human experience imparts. Therefore, leading experts caution that functional, safe humanoids remain a long-term goal due to persistent physical challenges. Analytical rigor—not rhetoric—is necessary to address these realities.

The Economics Problem

Money doesn't solve everything. Figure AI got $675 million in early 2024 and was valued at $39 billion by September 2025. But cash alone won't turn a demo into a reliable worker. Amazon tested a humanoid named Digit to move empty boxes. That's something, but it proves that easy, single-purpose jobs in controlled areas are still the only wins right now. General-purpose work? Not there yet. It all depends on robots working reliably on different tasks. But so far, it's just limited tests.

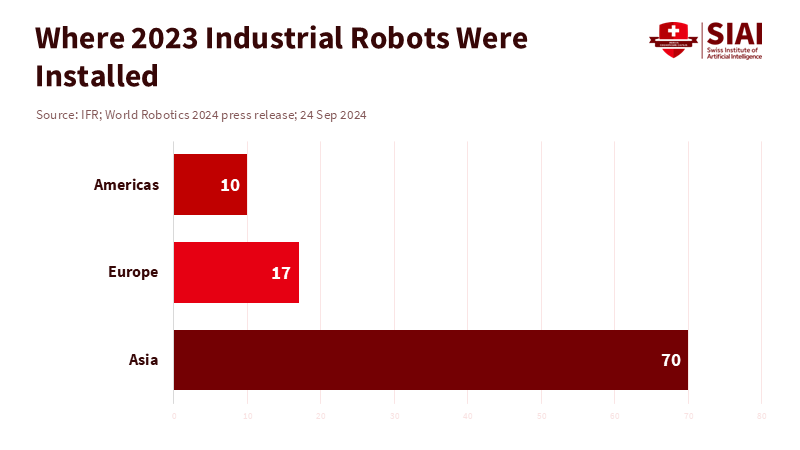

Then there's the energy issue. Work shifts are long, but batteries aren't. Agility says its new Digit lasts four hours on a charge, which is okay for set tasks with charging breaks. But that's not an eight-hour day in a messy place, let alone a home. Charging downtime, limited tasks, and a human babysitter make the business case weak. The robot market is growing, sure, but where conditions are perfect. Asia accounted for 70% of new industrial robot installations in 2023. But that doesn't mean humanoids are next; it just means tasks and environments need to be simple.

Quality counts too. Experts say that China's push for automation has led to breakdowns and durability issues, especially when parts are cheap. A recent analysis warned that power limits, parts shortages, and touch-sensitivity problems are blocking progress, even though marketing says otherwise. This doesn't mean there's no progress, but don't get carried away. Ignore this, and we'll waste money on demos instead of real research.

The Safety Problem

Safety isn't just a feeling. It's about standards. Factory robots follow ISO 10218, updated in 2025, which focuses on the whole job, not just the robot. Personal robots follow ISO 13482, which addresses risks and safety measures related to human contact. These aren't just rules. When a 60–70 kg machine with bad awareness falls over, it's dangerous, no matter how good the demo looks. Standards change slowly because people get hurt faster than laws can catch up.

That's why we should listen to the cautious voices. In late 2025, Rodney Brooks said we're over ten years from useful, minimally dexterous humanoids. Scientific American agrees: It's not just one missing part keeping humanoids out of our lives, but a lack of real-world smarts. If we make decisions based on flashy demos, we'll underfund research into touch, movement, and contact, where the real safety lies. The people who make standards will notice. We should too.

What to Fund: Research, Not Demos

The quickest way to address issues with humanoid robots is to improve their movement. Human muscles adjust to stiffness and give way a little. Electric motors don't. We need variable-impedance systems, tendon-driven designs, and soft robots that give way on contact. The goal isn't cool moves, but coping with the messy world. Tie funding to damage reduction, not cheering. If a hand can open a jar without smashing it—or know when to give up—that's worth paying for.

Next is touch. High-resolution touch sensors will change the way robots grab, more than hours of watching YouTube videos. We need lots of varied touch data, like a kid learning by making a mess. As LeCun says, without more data, robot smarts will stall. The answer is on-device data collection in living labs that look like kitchens and classrooms—with simulators that get friction right. Otherwise, the real world will always be out of reach.

Lastly, we need stamina. Warehouse work is long; homes are messy. Up to four hours of battery life is a start, but it limits what robots can do. Improving energy density is slow. And safety around heat and charging is vital. We need research into battery design, safe, fast charging, and graceful ways to shut down when power drops. And we need rules that punish duty-cycle claims that don't hold up. We should measure time between breakdowns, not marketing hype.

What should schools do?

Stop selling students on Android fantasies. Teach controls, sensing, safety, and testing. These skills apply to mobile robots, surgery systems, and factory automation, where the jobs are. Second, build industry labs where students test products on real materials and in messy conditions, with safety experts on hand. Third, reward designs that fail safely and recover, not just ones that work once. We need engineers who can turn cool demos into working systems.

Admins should use robots only for clear, low-risk tasks. Assign humanoids to simple workflows, as Amazon does, where mistakes are easy to fix. Invest the rest in other proven automation—like AMRs, fixed arms, and inspection systems. Use complex data—uptime, breakdowns, accidents—to guide decisions. Halt projects that don’t lead to reliable production. Politicians should back robotics projects with open results, not just hype. Ensure funding and incentives are tied to reporting failures, safety audits, and real-world testing. Support the development of sensors, actuators, and power systems that benefit many users. Advocate strict safety limits for heavy robots until risks are proven manageable.

Here's the practical test: The next three years, if we can build a robot that can fold T-shirts, carry a pot without spilling, and recover from a fall without help, we're onto something. These tasks aren't fun, but they touch on the physics, sensing, and control needed to deal with the real world. Solve them, and a safer service is possible. Skip them, and the hype will keep going, louder but not smarter. Let's be real. Investors will keep hyping. Press releases will hype robots. Some tests will work. But the robot future is still focused on machines doing specific jobs in specific places. That's valuable. It boosts productivity in boring places that pay the bills. The all-purpose humanoid will appear only when we earn it, by funding the unglamorous science of contact, control, and power.

Millions of robots are now in use, but almost none are humanoids in public. That's not a lack of imagination; it's reality. In robotics, the action is where limits can be designed and tested. The hype is somewhere else. If we want safe androids someday, we must change the system. Support touch sensors that last, actuators that give way, and batteries that work without trouble. Demand real tests, not just videos. Treat humanoid issues as research, not branding. Do this, and we might see a robot we can trust on the sidewalk.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Agility Robotics. “Agility Robotics Announces New Innovations for Market-Leading Humanoid Robot Digit.” March 31, 2025.

Amazon. “Amazon announces 2 new ways it’s using robots to assist employees and deliver for customers.” Company news page.

International Federation of Robotics (IFR). “Industrial Robots—Executive Summary (2024).”

International Federation of Robotics (IFR). “Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide.” Press release.

Innerbody. “Interactive Guide to the Muscular System.”

Reuters. “Robotics startup Figure raises $675 mln from Microsoft, Nvidia, other big techs.” Feb. 29, 2024.

Reuters. “Robotics startup Figure valued at $39 billion in latest funding round.” Sept. 16, 2025.

Rodney Brooks. “Why Today’s Humanoids Won’t Learn Dexterity.” Sept. 26, 2025.

Scientific American. “Why Humanoid Robots Still Can’t Survive in the Real World.” Dec. 13, 2025.

The Economy (economy.ac). “China tops 2 million industrial robots, but quality concerns persist.” Nov. 2025.

The Economy (economy.ac). “Humanoid Robots and the Division of Labor: bottlenecks persist.” Nov. 2025.

TÜV Rheinland. “ISO 10218-1/2:2025—New Benchmarks for Safety in Robotics.”

Unitree Robotics. “Unitree H1—Full-size universal humanoid robot (specifications).”

Yann LeCun (LinkedIn). “In 4 years, a child has seen 50× more data than the biggest LLMs.”

Comment