The New Kilowatt Diplomacy: How Himalayan Hydropower Is Being Built for AI

Published

Modified

AI data centers drive Himalayan hydropower Buildout deepens China–India water tensions Demand 24/7 clean, redundant AI power

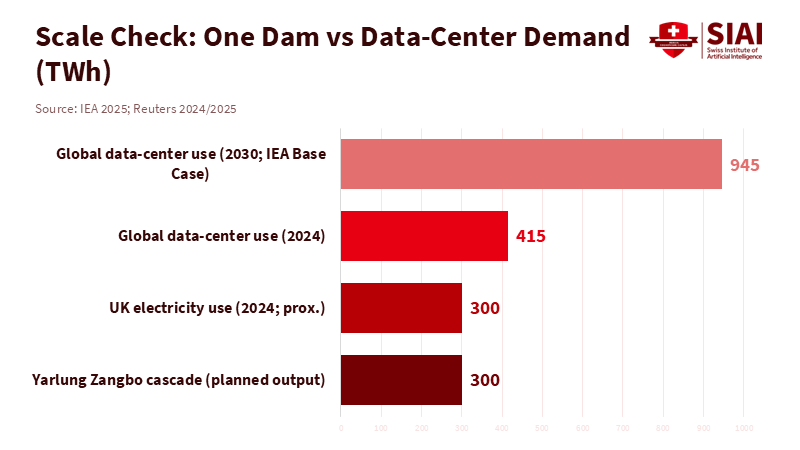

China is betting big on hydropower to fuel a new era of AI and digital growth. Its new dam on the Yarlung Zangbo (Brahmaputra River downstream) is projected to generate 300 billion kilowatt-hours per year—roughly the UK’s annual power use. If built, it would become the world's largest dam system, leveraging the steep Tibetan gorge for maximum energy generation. With costs topping $170 billion and operations targeted for the 2030s, the project underscores China’s strategy to pair frontier energy with next-generation computing. Beijing says it’s clean energy and good for the economy. But look closer: global data centers consumed around 415 TWh in 2024, with China accounting for a quarter and growing fast. This isn’t just about powering homes and factories. It’s about moving data centers to the Himalayas to harness hydro power—and the political power that comes with it.

Why Himalayan Hydro Power Data Centers Matter

Himalayan hydro power data centers are at the heart of a new global energy race for AI dominance. The International Energy Agency forecasts that data centers could demand up to 945 TWh by 2030—a leap from today. China and the US will drive most of this surge. For China, shifting computing to inland areas with abundant hydro power is a deliberate move to future-proof its AI ambitions. Massive new dams are less about local power needs and more about securing dedicated, reliable energy for AI infrastructure, creating a critical edge as energy becomes the digital world’s most significant constraint.

China’s already putting things in motion. They shipped some giant, fancy turbines to Tibet for a hydro power station that can handle the large elevation drop. News reports say they’re super-efficient and can create stations that make a ton of power. They also touted Yajiang-1, an AI computing center high in the mountains, as part of their East Data, West Computing plan. Even if some claims are overhyped, the message is clear: put computing where there’s tons of power and easy cooling, and back it all up with hydro power data centers in the Himalayas. That way, you lose less electricity in transmission, don’t need as much cooling, and you can lock in long-term, cheap power contracts because there’s lots of water available. At least for now.

Environmental, safety, and political risks converge around Himalayan hydro power data centers. Scientists predict worsening floods on the Brahmaputra River as glaciers melt, while downstream nations worry that even unintended Chinese actions could disrupt water flow and sediment transport. The site’s seismic instability adds another layer: as vital computing and power lines depend on these mountains, local disasters can quickly escalate to cross-border digital crises. Thus, these data centers are not only regional infrastructure—they are matters of national security for every nation that relies on this water and power.

China’s Reasoning

China’s reasoning is simple. It needs lots of reliable, clean energy for AI, cloud computing, and its national computer systems. In 2024, Chinese data centers already used a ton of power, about a quarter of the world’s total. That’s growing fast, and experts say China could add significantly more data-center demand by 2030, even with improved energy efficiency. Areas near the coast are running out of power, freshwater for cooling, and cheap land. But western and southwestern China have hydroelectric power, wind power, high-altitude free cooling, and space to build. The government has spent billions on inland computing centers since 2022 to move data west. So, building huge dams in Tibet seems less like a vanity project and more like a way to support its AI industry in the long term.

Beijing also sees it as a way to gain leverage. A dam system making 300 TWh is like having the entire UK’s electricity supply at your fingertips. That means the dams can stabilize power in western China, meet emissions goals, power data centers, and help export industries that want to use green energy. Chinese officials say the dam won’t harm downstream countries, and some experts say most of the river’s water comes from monsoon rains farther south. But trust is low. China hasn’t signed the UN Watercourses Convention and prefers less binding agreements, such as sharing data for only part of the year. India says data sharing for the Brahmaputra River has been suspended since 2023. Without a real agreement, even clean power looks like a political play.

The new turbines and AI computing centers in Tibet add a digital twist to the water issue. News reports talk about the Yajiang-1 center as green and efficient. State media keeps pushing the idea of moving data west as a way to help everyone. Put it all together, and it shows that computing follows cheap, clean power, and that China will handle things according to its own plans, not under outside pressure. That’s why it’s hard for other countries to step in. The real decisions are being made in line with China’s own goals, such as grid development, carbon targets, and its chip and cloud plans. Which is where Himalayan hydro power data centers fit in.

India’s Move

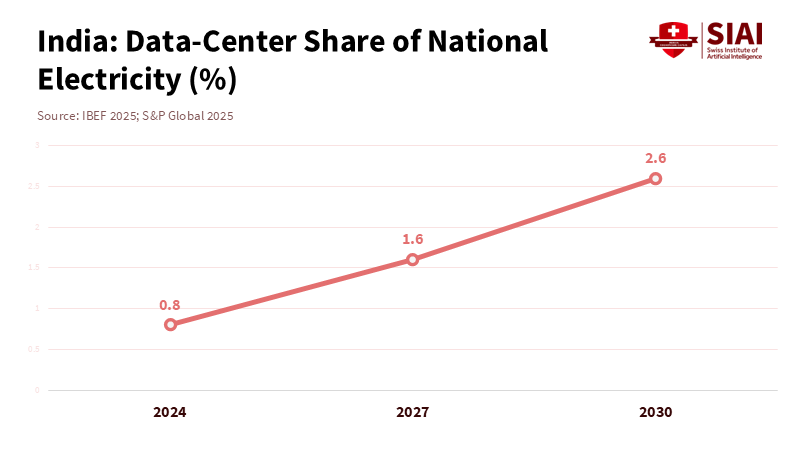

India can’t ignore what’s happening upstream. It has told China that it’s concerned and is working on its own hydropower and transmission projects in the Brahmaputra River area. In 2025, the government announced a major plan to generate significant power in the northeast by 2047, with many projects underway. The reasoning is both strategic and economic: establish its own water rights, make sure there’s enough water during dry seasons, and support Indian data centers and green industries in the region. This is happening! India’s data-center electricity use could triple by 2030 as companies and government AI projects grow. That means they’ll want more clean power contracts.

Officials in India say the national power grid can handle the increased demand and have mentioned pumped-storage and renewable energy projects to support new data centers. However, India and China share the same water source and face similar earthquake and security risks, meaning that actions taken by either country can directly affect the other. India’s response has included building its own dams, such as the large one in Arunachal Pradesh, even though local people are worried about landslides and being displaced. India has also encouraged Bhutan to sell more power to the Indian grid and has raised concerns about China’s dam with other countries. While these efforts may address supply concerns, they do not reduce the broader risk: without a clear treaty or enduring data-sharing agreements with China on the Brahmaputra, both countries' digital economies remain vulnerable to disputes, natural disasters, or intentional disruptions.

India also has opportunities. It can create a reliable green-computing area that combines hydro power and pumped storage in the northeast with solar power in Rajasthan and offshore wind in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, connected by high-capacity power lines. Data centers will still use a small share of power in 2030, but the choices made now will affect things for decades. If India’s power rules and markets support energy-efficient designs and continuous clean power, then those data centers can grow without facing new issues later on. That’s how India proactively takes the driver’s seat, putting in a compute-industrial policy.

What Needs to Change

Education and government leaders should understand that these are not distant energy concerns. If AI computing increasingly depends on Himalayan rivers, then any disruption—such as a natural disaster or power outage in the region—could directly affect universities, laboratories, schools, and their digital operations. Risk to the water supply becomes risk to digital learning and research capacity.

First, purchasing practices need to change. Institutions that buy cloud and AI services should ask where the energy comes from, how it aligns with real-time energy use, and how it affects river systems. Experts think data centers will use way more power by 2030, and AI is a big part of that. Contracts should favor companies that can prove they use real-time clean power and very little fresh water, specifically in areas where water is scarce. River risk is now a digital risk and should be mentioned in agreements.

Second, educators should be ready for climate-related computer problems. The Brahmaputra River basin is expected to experience longer, more intense floods. An earthquake or flood that knocks out a power station shouldn’t shut down school platforms, test systems, or hospital servers in another state. Governments should make sure there’s backup in different areas to simulate the Tibet outage.

Third, realize the limits of diplomacy. China didn’t vote for an agreement and prefers data sharing, while the US and Japan can raise concerns, support other options, and help India and Bhutan build their capabilities. This means the grid must reform, and a transparent source of AI power is required.

Finally, we need better statistics. China’s data center usage was a lot in 2024. India’s numbers are uncertain, too. Those who use heavy AI should provide public energy usage data, along with hourly data usage from the location. Green AI is a slogan without stats, and without public energy disclosure, ministries can steer work towards manageable grids. These things minimize the mountain power data centers compared to speeches and regional peace.

AI isn’t separate from these decisions. Himalayan hydro power data centers operate differently in India and China. There’s an old rivalry with no treaty to ease shocks, as shifting glaciers affect the flow, while outside powers have no control over domestic needs. The real test ahead is for decision-makers—procurement desks, planners, and educators—to secure digital and energy futures in the face of these growing risks. The choices made now will impact not just river flow, but the reliability and equity of AI for generations to come.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

IBEF. (2025, Oct 29). India’s data center capacity to double by 2027; rise 5x by 2030.

IEA. (2025). Electricity 2025 — Executive summary.

IEA. (2025). Energy and AI — Data-center and AI electricity demand to 2030.

Reuters. (2024, Dec 26). China to build world’s largest hydropower dam in Tibet.

Reuters. (2025, Jul 21). China embarks on world’s largest hydropower dam in Tibet.

S&P Global Market Intelligence. (2025, Sept 17). Will data-center growth in India propel it to global hub status?

Sun, H., et al. (2024). Increased glacier melt enhances future extreme floods in the southern Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies.

Comment