Beyond the AGI Hype: Why Schools Must Treat AI as Probability, Not Reasoning

Published

Modified

AI today is pattern-matching, not reasoning—resist AGI hype Redesign assessments for explanation, sources, and uncertainty Procure on outcomes and risk logs; keep humans in charge

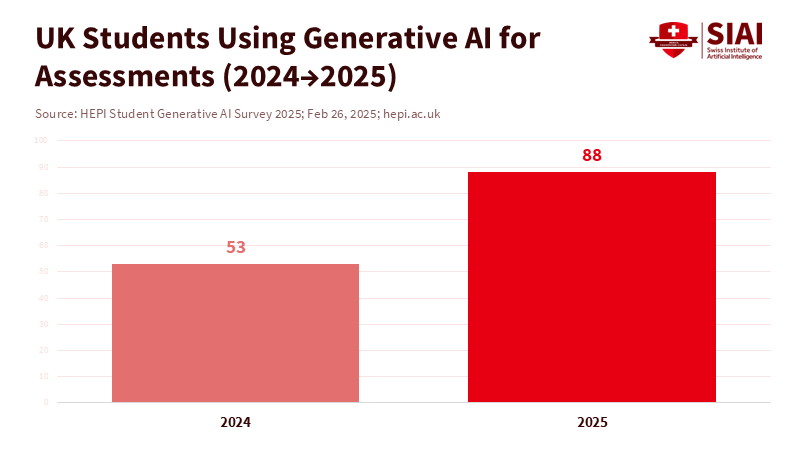

The core challenge facing schools this year is not whether to use AI, but how to understand what it is: an engine of sophisticated pattern prediction, not genuine reasoning. In the United Kingdom, 92 percent of university students now use generative AI for academic work, and 88 percent use it for assessments—evidence of changing day-to-day learning. The real risk is misinterpreting these tools as students do. If education systems treat probability engines as minds, they risk confusing fluency for proper understanding and speed for mastery. Policy should focus on what these systems actually do: they make predictions based on data, not on the way humans reason. By recognizing this, schools can make strategic decisions that enhance productivity and feedback without compromising standards or judgment.

AGI hype and the difference between probability and reasoning

Here is the main point. Today’s leading models mostly connect learned associations. Their outputs seem coherent because the training data are extensive and the patterns are rich. However, the mechanism remains statistical prediction rather than grounded reasoning. Consider two facts. First, training compute has exploded—roughly doubling every six months since 2010—because greater scale enables better pattern matching across many areas. Second, when evaluation is cleaned of leaks and shortcuts, performance declines. These two trends support a clear conclusion: gains come from more data, more compute, and more clever sampling at test time, not from a leap to general intelligence. Education policy should focus on robust probability rather than artificial cognition.

The phrase “reasoning models” adds confusion. Yes, some new systems take more time to think before answering and score much higher on complex math. OpenAI reports that its O1 line improved from 12 percent to 74 percent on the AIME exam with single attempts. That is real progress. However, it is narrow, costly, and sensitive to the choice of prompt design and evaluation. This tells us that staged searches over intermediate steps help with well-defined problems, not that the model has acquired human-like understanding. Schools should not confuse a better solver in contest math with a reliable explainer across complex, interdisciplinary tasks. In classrooms, we need tools that can retrieve sources, expose uncertainty, and withstand checks for contamination and hallucination. “More correct answers on a benchmark” is not the same as “more trustworthy learning support.”

AGI hype in the funding cycle and what it does to classrooms

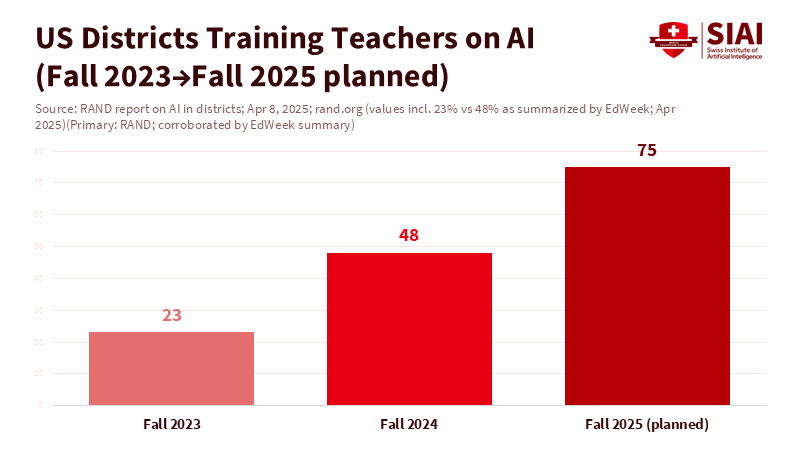

The money flowing into generative AI is significant and increasing. In 2024, private AI investment in the United States reached about $109 billion. Funding for generative AI climbed to around $34 billion worldwide, up from 2023. Districts are reacting: by fall 2024, nearly half of U.S. school districts had trained teachers on AI, a 25-point increase in just one year. Students are moving even faster, as the U.K. figure shows. This is the AGI hype cycle: capital fuels product claims; product claims drive adoption; and adoption creates pressure to buy more and make more promises. The danger is not in adoption itself. It is how hype blurs the line between what AI does well—summarizing, drafting, style transfer, code scaffolding—and what education needs for durable learning—argument, transfer, and critique.

Skepticism has not slowed use. A recent national survey in the U.S. found that about 70 percent of adults have used AI, and around half worry about job losses. In schools, many teachers already report time savings from routine tasks. Gallup estimates that regular users save about 6 hours a week, about 6 weeks over a typical school year. Those are significant benefits. But productivity gains come with risks. NIST’s updated AI risk guidance emphasizes how models can be fragile and overconfident, with hallucinations persisting even in the latest systems. Education leaders should recognize both sides of that equation: significant time savings on one hand, and serious failure modes on the other, amplified by hype.

Design for probability: assessment, curricula, and guardrails

If we acknowledge that current systems are advanced probability matchers, then policy must shape the workflow to leverage probability when helpful and limit it when it causes harm. Start with an assessment. Exams that reward surface fluency invite model-aided answers that look right but lack genuine understanding. The solution is not a ban; it is stress-testing. The U.K. proposal for universities to stress-test assessments is a good example: move complex tasks into live defenses, stage drafts with oral checks, and require portfolios that document the provenance of artifacts. Retrieval-augmented responses with citations should be standard, and students should be able to explain and replicate their steps within time limits. This is not a nostalgic return to pen-and-paper. It aligns with how these tools actually function. They excel at drafting but struggle to provide verifiable chains of reasoning without support. Design accordingly—and name the approach for what it is: a straightforward resistance to AGI hype.

Curricula should make uncertainty visible. Teachers can create activities in which models must show their sources, state confidence ranges, and defend each claim against another model or a curated knowledge base. This is where risk frameworks come in. NIST’s guidance and Stanford’s HELM work suggest evaluation practices that assess robustness, not just accuracy, across tasks and datasets. Dynamic evaluation also counters benchmark contamination. When tasks change, memorized patterns break, revealing what models can and cannot do. Building this habit in classrooms helps students distinguish between plausible and supported answers. It also fosters a culture in which AI is a partner that requires examination. That is the literacy we need far more than prompt tricks.

Managing the next wave of AGI hype in policy and procurement

Education ministries and districts face a procurement challenge. Vendors use the language of “reasoning,” but contracts must focus on risk and value. A practical approach is to write requirements that reflect probability rather than personhood. Demand audit logs of model versions, prompts (the input commands or queries given to AI), and retrieval sources. Require default uncertainty displays (visual markers of answer confidence) and simple toggles that enforce citations in student-facing outputs. Mandate out-of-distribution tests (tests on data different from what the model saw in training) during pilot projects. Tie payment to improvements in verified outcomes—reducing time-to-feedback, gaining in transfer tasks (applying knowledge in new contexts), or fewer grading disputes—not to benchmark headlines. Use public risk frameworks as a foundation, then add domain-specific checks, such as content provenance (a clear record of the source material) for history essays and step-wise explanations (detailed breakdowns of each stage in a solution) for math. This is how we turn AGI hype into measurable classroom value.

Teacher development needs the same clarity. The RAND (Research and Development) findings show rapid growth in training across districts, but the training content often lags behind actual tool use. Teachers need three things: how to use AI to speed up routine work without losing oversight, how to create assignments that require explanation and replication, and how to teach AI literacy in simple terms. That literacy should cover both the social aspects—bias (unfair preferences in outputs) and fairness—and the statistical aspects—what prediction means, how sampling (choosing from possible AI responses) can alter results, and why hallucinations (AI-generated errors) occur. UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) guidance is clear about the need for human-centered use. Make that tangible with lesson plans that encourage students to challenge model claims against primary sources, revise model drafts with counter-arguments, and label unsupported statements. Time saved is real; so must be the structure ensuring learning.

What this means for research, innovation, and the road to real reasoning

Research is moving quickly. Google and OpenAI have announced significant progress in elite math competitions and complex programming tasks, often by increasing test-time compute and exploring more reasoning paths. These accomplishments are impressive. However, they also show the gap between success in contests and everyday reliability. Many of these achievements depend on long, parallel chains of sampled steps and expensive hardware. They do not transfer well to noisy classroom prompts about local history or unclear policy debates. As new benchmarks come out to filter out bias and manipulation, we see a more modest view of progress in broad reasoning. The takeaway for education is not to overlook breakthroughs, but to view them as examples under specific conditions rather than as guarantees for general use. We should use them where they excel—such as in math problem-solving and code generation with tests—while keeping human understanding at the forefront.

We started with the number 92. It highlights the reality that generative AI is already part of the assessment process. The risk is not in the tool itself; it is in the myth that the tool can now “reason” like a student or a teacher. In reality, today’s systems are extraordinary engines of probability. Their scale and intelligent searching have made them fluent, helpful, and often correct, but not reliably aware of their limitations. When refined evaluations eliminate shortcuts and leaks, performance falls in ways that matter for education. That is why policy should resist AGI hype and design for the systems we actually have. Build assessments that value explanation and verification. Procure products that log, cite, and quantify uncertainty by default. Train teachers to use AI for efficiency while teaching students to question it. Keep human judgment—slow, careful, and accountable—at the core. If we accomplish this, we can gain the benefits of productivity and feedback without compromising standards or trust. We can also prepare for the day when reasoning goes beyond a marketing claim—because our systems will be ready to test it, measure it, and prioritize learning first.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Axios. “Americans are using and worrying about AI more than ever, survey finds.” December 10, 2025.

Deng, C. et al. “Investigating Data Contamination in Modern Benchmarks for Large Language Models.” NAACL 2024.

Epoch AI. “The training compute of notable AI models has been doubling roughly every six months.” June 19, 2024.

Gallup. “Three in 10 Teachers Use AI Weekly, Saving Six Weeks per Year.” June 24, 2025.

NIST. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0 update materials). July 25, 2024.

NIST. “Assessing Risks and Impacts of AI (ARIA) 0.1.” November 2025.

OpenAI. “Learning to reason with LLMs (o1).” September 12, 2024.

RAND Corporation. “More Districts Are Training Teachers on Artificial Intelligence.” April 8, 2025.

Stanford HAI. AI Index Report 2025. 2025.

The Guardian. “UK universities warned to ‘stress-test’ assessments as 92% of students use AI.” February 26, 2025.

UNESCO. “Guidance for generative AI in education and research.” Updated April 14, 2025.

Comment