Off-Planet Compute, On-Earth Learning: Why "Space Data Centers" Should Begin with Education

Published

Modified

Use space data centers to ease Earth’s compute and water strain—start with education Run low-latency classroom inference in LEO; keep training and sensitive data on Earth Pilot with strict SLAs, life-cycle audits, and debris plans before scaling

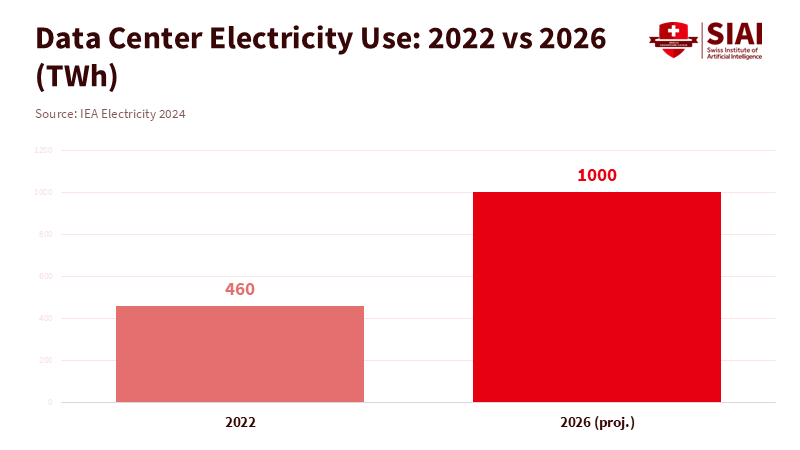

The key figure we should focus on is this: global data centers could use more than 1,000 terawatt-hours of electricity by 2026. This accounts for a significant share of global power consumption and is increasing rapidly as AI transitions from labs to everyday workflows. While this trend offers tangible benefits, it also creates challenges in areas with limited budgets, particularly in schools and universities. Water-scarce towns now face pressure from new server farms. Power grids can delay connections for years. Campuses see rising costs for cloud-based tools or experience slowdowns when many classes move online simultaneously. The concept of space data centers may sound like science fiction. Still, it addresses a pressing, immediate policy goal: expanding computing resources for education without further straining local water, land, and energy supplies. If we want safe, fair AI in classrooms, the real question is no longer whether the idea is exciting. The question is whether education should drive the initial trials, establish guidelines, and define the procurement rules that follow.

Reframing Feasibility: Space Data Centers as Education Infrastructure

Today's debate tends to focus on engineering bravado—can we lift racks into orbit and keep them cool? This overlooks the actual use case. Education needs reliable, fast, and cost-effective processing for millions of small tasks: grading answers, running speech recognition, translating content, and powering after-school AI tutors. These tasks can be spread out, stored, and timed. They do not all require immediate processing, as a Wall Street trader or a gamer does. The reframing is straightforward: view space data centers as a backup and support layer for public-interest computing. Keep training runs and the most sensitive student data on the ground. Offload bursty, repeatable processing jobs to orbital resources during peak times, nights, or exam periods. Education, not advertising or cryptocurrencies, is the best starting point because it offers high social returns, has predictable demand (at the start of terms and during exam periods), and can accept slightly longer processing times—if managed well—in many situations.

This viewpoint is critical now because the pressures on Earth-based resources are real. The International Energy Agency predicts that data center electricity use could surpass 1,000 TWh by 2026 and continue to rise toward 2030, even without a fully AI-driven world. Water resources are equally stretched. A medium-sized data center can consume about 110 million gallons of water per year for cooling. In 2023, Google alone reported over 5 billion gallons used across its sites, with nearly a third drawn from areas facing medium to high water shortages. When a district must choose between building a new school or a new power substation, the trade-off becomes significant. Shifting part of the computing layer to continuous, reliable solar power in orbit does not eliminate these trade-offs, but it can alleviate them if initial efforts prioritize public needs and include strict environmental accounting from the outset.

What the Numbers Say About Space Data Centers

Skeptics are right to ask for data, not just metaphors. Launch costs to put equipment into orbit have dropped, with SpaceX offering standard rates. Several companies are studying ways to make space data centers work and believe it could bring environmental benefits under certain conditions. Technology leaders are also researching prototypes that use solar energy and new communication methods. These projects are at an early stage, but offer an opportunity for policy planning to occur alongside engineering.

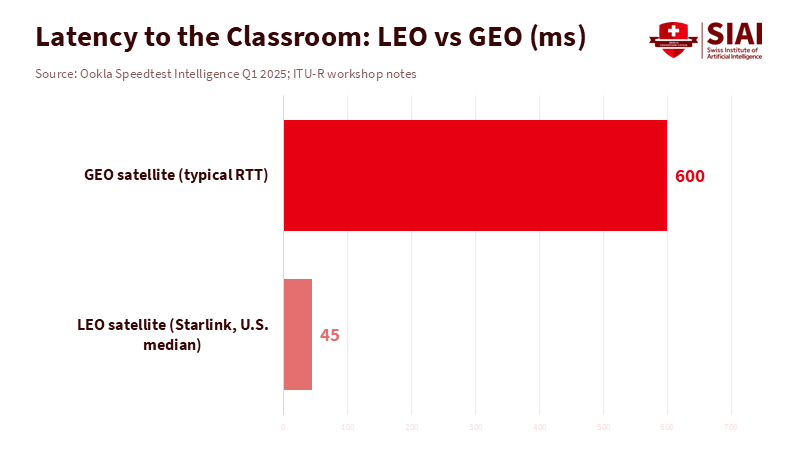

Latency is the second important metric for classrooms. LEO satellite networks already achieve median latencies in the 45-80 ms range, depending on routing and timing, which is comparable to many terrestrial connections. This is insufficient for high-frequency trading but acceptable for most educational technology tasks, such as real-time captioning and adaptive learning, when caching is used effectively. Peer-reviewed tests conducted in 2024-2025 show steady improvements in low-orbit latency and packet loss. The implication is clear: if processing is staged near ground points, and if content is cached at the orbital edge, numerous educational tasks can run without noticeable delays. Training large models will remain on Earth or in a hybrid cloud, where power, maintenance, and compliance are more manageable. However, the inference tier—the part that impacts schools—can be moved. This is where the new capacity offers the most support and causes the least disruption.

Latency, Equity, and the Classroom Edge with Space Data Centers

The case for equity is strong. Rural and small-town schools often have limited access to reliable infrastructure. When storms, fires, or heat waves occur, they are the first to lose service and take the longest to recover. Space data centers could serve as a floating edge, keeping essential learning tools operational even when local fiber connections are down or power is limited. A school district could sync lesson materials and assessments with orbital storage in advance. During outages, student devices can connect via any available satellite link and access the cached materials, while updates wait until connections stabilize. For special education and language access, where speech-to-text and translation are critical during class, this buffer can make a major difference. The goal is to design for processing near content, rather than pursuing flashy claims about space training.

The environmental equity argument is also essential. Communities near large ground data centers bear the burden of water usage, diesel backups, and noise. Moving some processing off-planet does not eliminate launch emissions or the risk of space debris, but it can reduce local stressors on vulnerable watersheds. To be credible, however, initial efforts should provide complete reports on carbon and water use throughout the life cycle: emissions from launches, in-space operations, de-orbiting, debris removal, and the avoided local cooling and water use. Educators can enforce this transparency through their purchasing decisions. They can require independent environmental assessments, mandate end-of-life de-orbiting plans, and tie payments to verified ecological performance rather than mere promises. When approached in this manner, space becomes a practical tool for relieving pressure on Earth as we develop more sustainable grids and regulations.

A Policy Roadmap to Test and Govern Space Data Centers

The main recommendation is to launch three targeted, controlled pilot programs over two school years to shape education technology proactively. The first pilot focuses on content caching, in which national education bodies and open-education providers pre-position high-use resources for reading support in orbit via low-orbit satellites, targeting under 100 ms latency and strict privacy. The second pilot tests AI inference by evaluating speech recognition, captioning, and formative feedback on orbital nodes, ensuring reliable terrestrial backups and maintaining logs for bias and error assessment. The third pilot provides emergency continuity during outages or storms, prioritizing students needing assistive tech. Each pilot includes a ground control group to measure actual educational gains and improvements in access, not just network metrics.

Procurement and governance must go hand in hand—take decisive steps to shape them now. Ministries and agencies should immediately design model RFPs that pay only for actual processing, limit data in orbit to 24 hours unless consent is given, and require end-to-end encryption managed on Earth. Insist that providers map education rules like FERPA/GDPR to orbital processes, enforce latency standards, and fully commit to zero-trust security. Demand signed debris-mitigation and de-orbiting plans in every contract and tie payments to verified environmental outcomes. Do not wait for commercial offers: by setting these requirements now, education can become the leader—and the primary beneficiary—in the responsible, innovative adoption of space data center technology.

The Market Will Come—Education Should Set the Terms

The commercial competition is intensifying. Blue Origin has reportedly been working on orbital AI data centers, while SpaceX and others are investigating upgrades that could support computing loads. Startups are proposing “megawatt-class” orbital nodes. Tech media often portrays this as a battle among large companies, but the initial steady demand may come from the public sector. Education spends money in predictable cycles, values reliability over sheer speed, and can enter multi-year capacity agreements that reduce risks for early deployments. The ASCEND study indicates feasibility; Google’s team has shared plans for a TPU-powered satellite network with optical links; academic research outlines tethered and cache-optimized designs. None of this guarantees costs will be lower than ground systems in the immediate future. Still, it presents a path for specific, limited tasks where the overall cost, including water and land, is less per learning unit. That should be the key measure guiding us.

What about the common objections? Cost is a genuine concern, but declining launch prices and improved packing densities change the game. A tighter focus on processing tasks and caching means less reliance on constant, high-bandwidth data transfers. Latency is manageable with LEO satellites and intelligent routing, as field data now shows median latencies in mature markets of tens of milliseconds. Reliability can be improved through backup systems, graceful degradation of ground systems, and resilience during disasters. Maintenance is a known challenge; small, modular units with planned lifespans and guaranteed de-orbit procedures mitigate that risk. And yes, rocket emissions are significant; this is where complete life-cycle accounting and limits on the number of launches per educational task must be included. The underwater Project Natick initiative offers a helpful analogy: careful design in challenging environments can lead to better reliability than on land. The same discipline should apply to space. If these conditions are met, pilots can advance without greenwashing.

The path to improved learning goes straight through computing. We can continue to argue over permits for substations and water rights, or we can introduce a new layer with different demands and challenges. The opening statistic—more than 1,000 TWh of electricity used by data centers by 2026—is not just a number for a school trying to keep devices charged and cloud tools functioning. It explains rising costs, community pushback, and why outages affect those with the least resources first. Space data centers are not a magic solution. They are a way to increase capacity, reduce local pressures, and strengthen the services students depend on. If education takes the lead in this first round—through small, measurable pilots, strict privacy and debris regulations, and performance-based contracts—we can transform a lofty goal into a grounded policy achievement. The choice is not between dreams in space and crises on Earth. It is about allowing others to dictate the terms or establishing rules that prioritize public education first. Now is the time to draft those rules.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ascend Horizon. (n.d.). Data centres in space.

EESI. (2025, June 25). Data Centers and Water Consumption.

Google. (2025, Nov. 4). Meet Project Suncatcher (The Keyword blog).

IEA. (2024). Electricity 2024 – Executive summary.

IEA. (2025). Energy and AI – Energy demand from AI.

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (2025, Oct. 17). Data Drain: The Land and Water Impacts of the AI Boom.

Microsoft. (2020, Sept. 14). Project Natick underwater datacenter results.

Ookla. (2025, June 10). Starlink’s U.S. performance is on the rise.

Reuters. (2025, Dec. 10). Blue Origin working on orbital data center technology — WSJ.

Scientific American. (2025, Dec.). Space-Based Data Centers Could Power AI with Solar.

SpaceX. (n.d.). Smallsat rideshare program pricing.

Thales Alenia Space. (2024, June 27). ASCEND feasibility study results on space data centers.

The Verge. (2025, Dec. 11). The scramble to launch data centers into space is heating up.

Vaibhav Bajpai et al. (2025). Performance Insights into Starlink’s Latency and Packet Loss (preprint).

Wall Street Journal. (2025, Dec. 11). Bezos and Musk Race to Bring Data Centers to Space.

Comment