Stop Hiring on AI Slop: Build Proof of Originality into Education and Work

Published

Modified

AI slop is flooding education and hiring, drowning out real skill Fix the system by verifying process—observed writing, evidence-linked claims, and a short oral defense Set provenance standards and incentives so accountable, source-grounded work beats paste

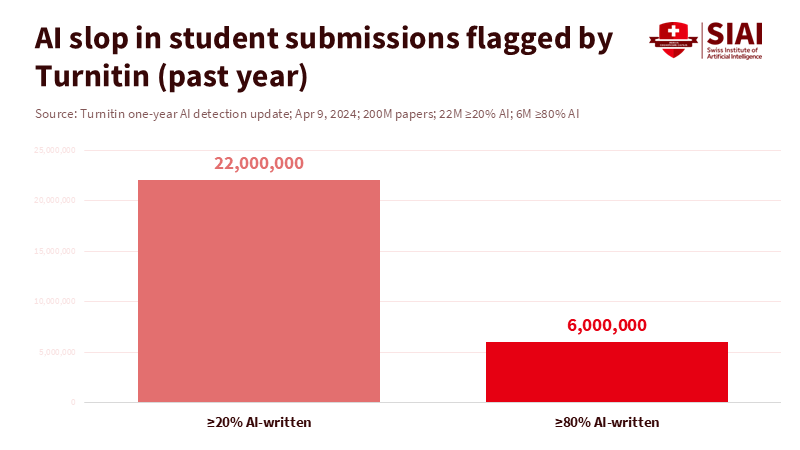

A single number summarizes the threat: Turnitin’s AI-writing tool scanned 200 million student papers in one year; 11% contained at least 20% AI text, and 3% were mostly AI-written. This is a structural issue, not a minor annoyance. AI-generated content undermines how we evaluate skill, knowledge, and trust in hiring, admissions, and publishing. The International Committee of the Red Cross found that chatbots fabricate archival citations. Retraction Watch tracks over 50,000 retractions and 300+ "hijacked" journals, showing how automation threatens research integrity. Google now targets “scaled content abuse,” much of it AI-driven. Unless we verify the originality process, not just the output, we risk losing the ability to certify real skill and knowledge.

AI slop is not spam; it is a structural risk

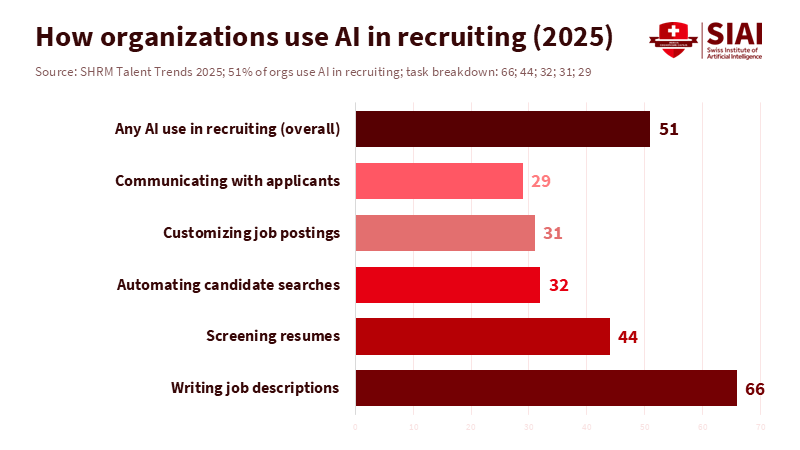

Spam clogs inboxes, while AI slop distorts signals. In education and hiring, we use writing to assess competence and judgment. The old cues—polished grammar, predictable structure, business-like phrasing—were not perfect but at least rare. Now, they are plentiful. Half of job seekers report using generative tools to create CVs and cover letters, while many HR teams use AI to sift through the resulting flood. This creates a cycle: generic applications pass generic filters, while candidates with genuine, distinctive work must prove they are not machines. The outcome is less precision, more effort, and increasing cynicism on both sides. The main risk is not the existence of AI but that our evaluation systems were designed for a different cost structure in producing text.

The research ecosystem shows how far the problem can expand if we do nothing. Large-scale AI content has contributed to a market filled with fake or hijacked journals, citation spam, and synthetic references. Retraction Watch’s database now includes over 50,000 retractions, and its Hijacked Journal Checker has more than 300 titles. Even respected institutions are receiving “record requests” for non-existent journals and issues created by chatbots. When gatekeepers rely on surface features rather than verifiable links, slop enters the system. Google’s 2024 policy change—targeting “scaled content abuse”—signals that high-volume AI publishing harms quality at a web scale. Education and hiring are smaller systems, but they share the same mechanics; if we want accurate signals, we must raise the cost of generating unreliable text and lower the cost of checking provenance.

From detection to design: a proof-of-originality pipeline for AI slop

The impulse to combat AI slop with AI detectors is reasonable, and in some cases, useful. However, detectors cannot do it alone; their error rates and bias risks are well-documented. A better approach is to redesign. Replace “trust the document” with “trust the process that produced it.” For admissions and hiring, this means three interconnected steps. First, require observed writing: a timed, supervised writing session on a prompt related to the role or course. It can be brief—45 to 90 minutes—but this output becomes the staff’s primary writing sample. Second, require evidence-linked claims: every factual claim must include a working identifier (DOI, ISBN, ISSN, or stable URL), and candidates must submit an evidence table with these IDs. Generic text is acceptable; untraceable claims are not. Third, include a quick oral defense within 48 hours. Applicants explain their key choices, sources, and trade-offs. You don’t need to guess who wrote the words; you assess who owns the ideas and can navigate the sources.

These steps are practical and proven. Notably, credibility issues arise when institutions rely solely on static documents and automated scores. When organizations shift to process evidence—timestamps, version histories, reference IDs, brief oral defenses—the slop disappears. Platforms that faced AI-generated floods moved from banning outputs to revising contribution processes, since moderators could not reliably identify authorship at scale. The lesson for hiring and admissions is to design a proof-of-originality pipeline that is hard to fake and easy to verify. This approach speeds up scoring, reduces uncertainty, and rewards genuine explanation over pasting.

Guardrails without unfair harm: make AI slop costly, not students

We must also avoid a second trap: turning faulty detectors into courtroom evidence. Studies show that popular AI detectors misclassify non-native English writing at high rates, and some universities have paused or adjusted disciplines led by detectors due to bias and false positives. K-12 teachers report similar uncertainties and concerns; only a few believe AI tools are more helpful than harmful, and many feel pressured to adopt them despite the integrity risks. The message is clear. Detectors can detect anomalies, but processes must determine which cases they are. A flag should initiate a discussion, not a judgment. When we create assessments that build resilience—such as observed writing, source-linked claims, and swift oral defenses—the need for high-stakes detection decreases.

Fairness requires small but significant changes. Use oral defenses in pairs so no single evaluator controls the outcome. Provide prep windows with open materials to level the playing field for second-language speakers who may think well but write slowly. Normalize assistive tools with provenance—reference managers, code notebooks with execution logs, and note-taking apps that track edits—so students and candidates can clearly show their process. Reserve strict penalties for deceit regarding the process (e.g., submitting bought work) rather than for the presence of AI aids. We will still need escalation paths for severe cases, and we must teach the difference between help and substitution. But if we center incentives around evidence and ownership, the slop engine loses its fuel: there is no reason to submit text you cannot defend with sources you can find.

Incentives and standards: raise the cost of AI slop at the source

AI slop flourishes when institutions reward output volume or surface polish without verifying provenance. We need to change the economics. In publishing, this shift has begun: visible retraction counts, lists of hijacked journals, and improved editorial processes are altering the incentives for authors and publishers. In search, Google’s anti-scaling content abuse policy suppresses low-value, factory-produced pages, encouraging creators to produce referenceable, practical work. Education and hiring should follow suit. Make source-verified writing the standard. Require that any factual claim include a working DOI or similar stable identifier, and that the applicant’s evidence table matches the text. Connect this to random checks by evaluators who actually click through sources. When a claim checks out, the candidate’s score grows; when it fails, the burden remains with the claimant. This is how we maintain speed while restoring trust.

Standards bodies can assist. Admissions platforms can incorporate DOI/ISBN fields, complete with live validation. Applicant-tracking systems can facilitate observed-writing modules and securely record brief oral defenses. Journals and universities can provide data on reference quality—i.e., the percentage of claims with valid identifiers—alongside acceptance rates. HR associations track AI use in hiring; they can issue guidelines that favor tools that log processes and maintain auditable trails over opaque “fit” scores. Because job seekers increasingly rely on AI tools for applications, we should be clear about expectations: using AI for drafts is fine if the candidate can demonstrate source understanding and defend their choices in a brief recorded conversation. The message is “no AI.” The message is “no untraceable text.”

What proof of originality is required, starting tomorrow morning?

For educators, the primary focus should be on shifting assessments toward evidence-based and oral formats. Retain essays, but make key work come from observed sprints and brief defenses. Require a simple evidence table with DOIs or ISBNs for all factual claims. Provide examples of good “reference hygiene” to help students understand what quality looks like. Reduce reliance on detectors; use them only as preliminary checks. Publish clear policies distinguishing acceptable drafting help from substitution. When students know they must explain their choices, they become engaged in the sources and the reasoning, not just the writing.

For administrators, the emphasis should be on workflow and training. Provide the necessary tools—secure proctoring for short writing sprints, evidence-table templates, and time for 10–15 minute oral defenses. Train staff to evaluate process records and conduct quick, respectful orals to assess ownership, not just memorization. Clearly define appeal processes when detector flags arise, requiring staff to reference process evidence—version history, source checks, oral notes—before making decisions. Communicate this change clearly; applicants will adapt to whatever the system values, as will the coaching industry. If we prioritize provenance and explanation, we reduce unoriginal submissions and increase actual critical thinking.

For policymakers, the request is straightforward: establish requirements for provenance. Encourage accreditation standards that mandate source-linked claims for written assessments and recommend oral defenses for major submissions. Support public-interest tools—open DOI validators, link checkers, evidence-table creators—that simplify the process of doing this correctly. Fund research on fairness in AI detection and on assessment designs that lessen reliance on fragile scoring systems. We should not regulate tools; we should regulate proof.

Anticipating the critiques

One critique is that this creates overhead. It may seem to add steps. In reality, it streamlines the process: fewer ambiguous cases, fewer emails about “who wrote this,” and significantly less time wasted on guesswork. Short, observed writing followed by a ten-minute oral is quicker than days of emails and committee meetings over AI-detector scores that no one trusts. Another critique is that this may disadvantage shy or non-native candidates. This is a valid concern; it’s why orals should be brief, structured, and paired with prep windows and open materials. The aim is to assess ownership, not performance. Evidence tables also aid in this respect; they favor careful readers regardless of fluency or accent.

A third critique is that detectors are improving, so why change assessments? Detectors will become better; they also have limitations. Evidence shows that they often misclassify non-native writers, and universities have paused enforcement of detector flags for this reason. These tools cannot serve as the sole decision-makers. Use them effectively—spotting anomalies in volume—but move the burden of certainty to processes we control: observing work, verifying sources, and discussing reasoning. The wider environment is shifting. Google is reducing the visibility of low-quality content. Editors are becoming stricter with reference integrity. Our classrooms and hiring practices should follow this trend.

Return to that initial number. If 11% of a 200-million-paper collection shows significant AI-written content, then writing alone has lost its value. This does not mean writing has lost its importance. It indicates we need to redefine what writing signifies. A document lacking provenance conveys little about skill; a document with clear origins, source-linked claims, and an oral defense conveys much. This shift will also enhance hiring. If half of the applicants are using AI to generate application text, then the only way to recover meaningful signals is to value what cannot simply be copied: judgment about sources, the ability to explain decisions, and the skill of linking claims to verifiable evidence. This is not a retreat from technology; it is a restoration of trust. Establish proof of originality at the gates, and AI slop will recede to where it belongs—background noise that no longer determines anyone's future.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AOL (2025). AI Slop Is Spurring Record Requests for Imaginary Journals (S. American syndication).

Business Insider (2025). 59% of young people see AI as a threat to jobs (Harvard Youth Poll).

Google (2024). Core update and new spam policies: scaled content abuse.

Pew Research Center (2024, 2025). Teachers’ views on AI in K-12; Teens’ use of ChatGPT doubled.

Retraction Watch (2024). Retraction Watch Database; Hijacked Journal Checker.

Scientific American (2025). AI Slop Is Spurring Record Requests for Imaginary Journals.

SHRM (2024–2025). AI in HR and recruiting: usage statistics.

Stack Exchange / Stack Overflow Meta (2023). AI-generated content policy and moderation conflict.

Stanford HAI / Liang et al. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers (Patterns).

Turnitin (2023–2025). AI detection one-year reports and guidance; 200M+ papers reviewed; detection rates.

Wired (2024). Students are likely writing millions of papers with AI.

Comment