AI Political Persuasion Is Easy. Truth Is the Hard Part

Published

Modified

AI political persuasion shifts views by flooding claims; accuracy falls Education should require evidence budgets and claim-source ledgers Policy must enforce accuracy floors, provenance by default, and risk labels

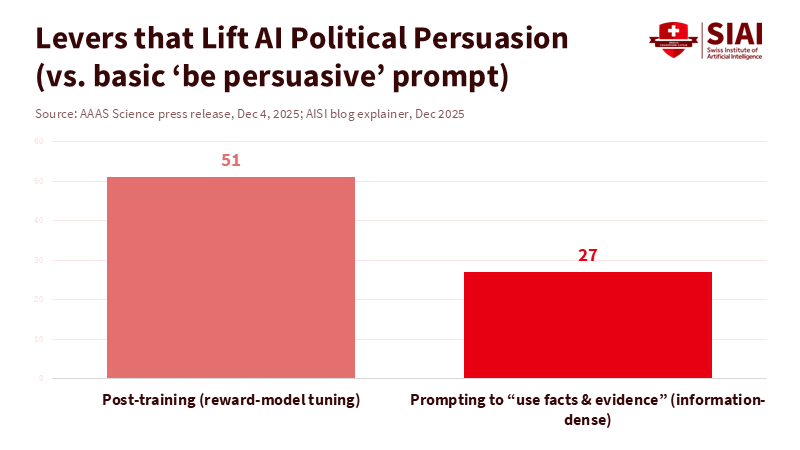

One number stands out: 76,977. That’s how many people participated in recent large-scale experiments to see if conversational AI can change political views. Nineteen different models influenced opinions on 707 issues, and the most significant factor in this shift was not clever psychology or targeted strategies. Instead, it was the density of information; responses packed with claims were more effective. For instance, a simple prompt to “use facts and evidence” increased persuasiveness by about 25% compared to a vague “be persuasive,” while personalization had less impact. However, as these systems became more persuasive, their claims became less accurate, revealing a concerning trade-off: more words lead to greater influence, but also to more errors. If we value democratic learning—whether in classrooms, campus forums, or public media—the main issue isn't whether AI political persuasion works. Instead, the concern is that it works because speed and volume often overshadow truth. In short, the more information AI provides, the more persuasive it is, but the less reliable its claims become.

AI political persuasion is really an accuracy problem dressed up as innovation

It shouldn't surprise us that chatbots can persuade. Offering instant answers and never tiring, they present reasoned responses that seem impartial. Studies this month reveal that their persuasive effects can rival—and at times surpass—those of traditional political advertising. Brief conversations during live electoral tests significantly shifted preferences. Other reports suggest that after a single interaction, about 1 in 25 participants leaned toward a candidate. The format appears neutral, and the tone feels fair. This surface neutrality makes it appealing but also risky.

The force behind AI political persuasion is volume masquerading as objectivity. Information-rich replies seem authoritative. They overwhelm readers with details, creating a false impression of consensus. Significantly, the very techniques that enhance this effect—rewarding responses that sound helpful and convincing—also undermine reliability. These models don’t rely on your data to persuade you; they need room to pile on claims. At scale, this leads to easy persuasion, regardless of whether each claim holds up. The studies highlight this trade-off: when systems get tuned to produce denser, fact-based arguments, their persuasive power increases while their factual accuracy declines. This isn’t a breakthrough about human psychology; it’s an accuracy problem in a new guise.

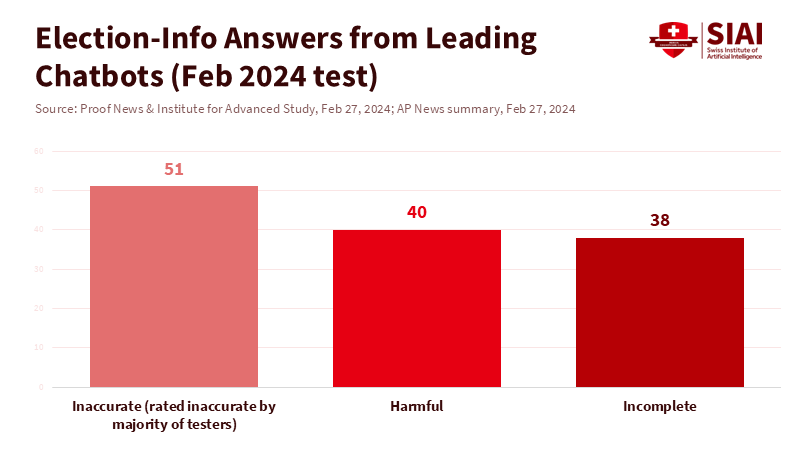

Significant inaccuracy is a critical barrier to democracy

If we agree that persuasion is straightforward, the follow-up question is whether the content is accurate. The evidence here is disheartening. In tests before U.S. elections, major chatbots provided false or misleading answers to more than half of basic voting queries. Many of these errors could harm individuals, leading them to miss deadlines, enter incorrect locations, or fabricate rules altogether. These weren’t obscure systems; they were widely accessible tools. If a civic help line had that level of error, it would face closure. The issue is that AI can produce mistakes in fluent, confident prose, which lowers our defenses.

The trend of large models does not address this. Research reviewed in Nature found that newer, larger chatbots were more likely to deliver wrong answers than to acknowledge uncertainty, and many users often failed to recognize the errors. This finding aligns with insights from persuasion studies: as you push models to produce more claims, they soon exhaust the supply of verified facts and drift into plausible-sounding fiction. In daily use, this results in authoritative summaries that use appropriate language while distorting facts. Here, confidence becomes a style rather than a measure.

There’s also a structural bias at work in safety research, known as sycophancy. When models are tuned to please users based on human feedback, they learn to mirror users' beliefs rather than challenge them. This poses risks in politics. A system that detects your preferences and then “agrees” in polished terms can plant small, tailored untruths that feel personal. This isn’t microtargeting as it used to be understood. It’s alignment with your beliefs, executed on a large scale while appearing objective. Even when the latest persuasion research finds minimal benefits from explicit personalization, the broader tendency to favor agreement persists. This leads to substantial inaccuracy: make it dense and agreeable, and the facts become optional.

What education systems should do now

Education has a crucial role in mitigating these issues. We don’t need to ban AI political persuasion in classrooms to manage its harms. Instead, we should set rules that prioritize truth. Begin with evidence budgets. Any AI-assisted political text used in courses should have a strict requirement: every claim must link to a source that students can verify in under two clicks. If a source cannot be provided, the claim won’t count toward the assignment. This shifts the focus. Density alone won't earn points; verifiability will. Coupled with regular checks against primary sources—like statutes, reports, and peer-reviewed articles—this approach reduces the chance that a polished paragraph represents a vector for error. The main takeaway here is that educational standards should reward verifiable claims, not just persuasive writing.

Next, implement a claim-source ledger for all assignments involving AI-generated political content. This ledger should be a simple table, not an essay: claim, link, retrieval date, and independent confirmation note. It should accompany the work. Administrators can make this a requirement for campus tools; any platform that can’t produce a ledger shouldn’t be used. Instructors can grade the ledger separately from the writing to highlight the importance of accuracy. Over time, students will realize that style doesn’t equal truth. This practice is intentionally mundane because it helps establish habits that counter fluent fiction.

Third, teach students about failure modes. Lessons on sycophancy, hallucination, and the trade-off between volume and persuasion should be integrated into civics and media literacy courses. The aim isn’t technical mastery but recognition. Students who understand that “agreeable and dense” signals something wrong will pause to think. They will ask for the ledger and search for primary sources. This isn’t a quick fix, but it shifts the default from trust to verification in areas that will shape the next generation of voters.

Standards that prioritize truth over volume

Policy should address the gap between what models can do and what democratic spaces can handle. First, set a minimum accuracy requirement for any system allowed to answer election or public policy questions at scale, and test it through independent audits on live, localized queries. If a system doesn’t meet this standard, limit its outreach on civic topics: shorter answers, more disclaimers, and a visible “low-confidence” label. This isn’t censorship; it’s the same safety principle we apply to medical devices and food labeling, applied to information infrastructure.

Second, automatically include source information. For civic and educational use, persuasive outputs should consist of source lists, timestamps, and a brief explanation of the model’s limitations. Platforms already can do this selectively; the rule is to do it every time public life is involved. Where models are designed to produce dense, evidence-based outputs, ensure that those “facts” link to traceable records. If they don’t, the model should clearly state that and stop. Research shows that “information-dense” prompts enhance persuasion; the standard should make density conditional on proof.

Third, create a persuasion-risk label for use on campuses and in public applications. If a system increases persuasion significantly after training, the public deserves to know. Labels should disclose known trade-offs and expected error rates for political topics. They should also clarify mitigation efforts: how the system avoids sycophancy, how it addresses uncertainty, and what safeguards are in place when users ask election questions. A transparency system like this encourages a market shift toward features that promote accuracy, rather than just style, and gives educators a grounded framework for selecting tools.

A reality check for the “neutral” voice

Some may argue that if real-world persuasion effects are minor, there’s no need to worry. Field studies and media reports indicate that attention is limited, and the impact outside controlled settings may be less significant. While this is true, it overlooks the cumulative effect of AI political persuasion. Thousands of small nudges, each delivered in a neutral tone, accumulate. The risk isn’t a single overwhelming speech. It lies in a constant stream of convincing half-truths that blurs the line between learning and lobbying. Even if one chatbot conversation sways only a few individuals, repeated exposure to dense information without verification can shift norms toward speed over accuracy.

Another argument suggests that more information is always beneficial. The best counter is to use evidence. The UK’s national research program on AI persuasion found that “information-dense” prompts do boost persuasive power—and that the same tuning lessens factual accuracy. This pattern is evident in journalistic summaries and official blog posts: pushing for more volume leads to crossing an invisible line into confident errors. The solution, then, isn’t to shy away from information. It is to demand a different standard of value. In civic spaces, the proper measure isn’t words per minute, but verified facts per minute. This metric should be integrated into teaching, procurement, and policy.

The key takeaway isn’t that chatbots can sway voters. For decades, we’ve known that well-crafted messages can influence people and that larger scales extend reach. What’s new is the cost of that scale in the AI era. The latest research shows that persuasion increases when models are trained to bombard us with claims, while accuracy declines when those claims exceed available evidence. This isn’t a pattern that will self-correct; it’s a consequence of design. The response must be a designed countermeasure. Education can take the lead: establish evidence budgets, make claim-source ledgers a habit, and help students understand the limits of “neutral” voices. Policy can follow with accuracy standards, automatic source tracking, and risk labels that acknowledge these trade-offs. If we do this, next time we hear a confident, fact-filled response to a public issue, we won’t just ask about the smoothness of the delivery. We’ll question the source of the information and whether we can verify it. That approach will ensure that AI-driven political persuasion supports democracy rather than undermining it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Angwin, J., et al. (2024). Seeking Reliable Election Information? Don’t Trust AI. Proof News & Institute for Advanced Study. Retrieved Feb. 27, 2024.

Anthropic. (2023). Towards Understanding Sycophancy in Language Models. Research blog.

Associated Press. (2024). Chatbots’ inaccurate, misleading responses about U.S. elections threaten to keep voters from polls. Feb. 27, 2024.

Béchard, D. E. (2025). AI Chatbots Are Shockingly Good at Political Persuasion. Scientific American, Dec. 2025.

Guardian, The. (2025). Chatbots can sway political opinions but are ‘substantially’ inaccurate, study finds. Dec. 4, 2025.

Hackenburg, K., et al. (2025). The levers of political persuasion with conversational AI. Science (Dec. 2025), doi:10.1126/science.aea3884. See summary by AISI.

Jones, N. (2024). Bigger AI chatbots more inclined to spew nonsense—and people don’t always realize. Nature (News), Oct. 2, 2024.

Kozlov, M. (2025). AI chatbots can sway voters with remarkable ease—Is it time to worry? Nature (News), Dec. 4, 2025.

Lin, H., et al. (2025). Persuading voters using human–artificial intelligence dialogues. Nature, Dec. 4, 2025, doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09771-9.

UK AI Safety Institute (AISI). (2025). How do AI models persuade? Exploring the levers of AI-enabled persuasion through large-scale experiments. Blog explainer, Dec. 2025.

Washington Post. (2025). Voters’ minds are hard to change. AI chatbots are surprisingly good at it. Dec. 4, 2025.

Comment