When Algorithms Say Nothing: Fixing Silent Failures in Hiring and Education

Published

Modified

AI tools exclude people through missing data and bugs Count “no-decision” cases and use less-exclusionary methods with human review Set exclusion budgets, fix data flows, and publish exclusion rates

A quiet fact sets the stakes. In 2024, a global HR survey found that 53% of organizations already use AI in recruitment, often to filter résumés before a human ever reviews them. Yet in a recent, legally required audit of a résumé-screening tool, 11.4% of applicant criteria were labeled “uncertain” and excluded from analysis. In another audit of a central matching platform, over 60 million applications had unknown race or ethnicity fields, making fairness hard to test and easy to overlook. When systems cannot decide or measure, people fall out of view. This is algorithmic exclusion, and it is not a rare issue; it is a structural blind spot that eliminates qualified applicants, obscures harm, and weakens trust in AI across education and work. We can reduce bias only if we also address silence—those moments when the model returns nothing or hides behind missing data-so stakeholders feel reassured that no one is invisible.

Algorithmic exclusion is systemic, not edge noise

The familiar story about unfair algorithms focuses on biased predictions. But exclusion starts earlier. It begins when models are designed to prioritize narrow goals like speed, cost, or click-through rates, and are trained on data that excludes entire groups. It worsens when production code is released with common software defects. These design, data, and coding errors together push people outside the model’s view. Leading institutions now recognize “no prediction” as a significant harm. A recent policy proposal suggests that regulations should recognize algorithmic exclusion alongside bias and discrimination, as sparse, fragmented, or missing data consistently yield empty outputs. Suppose the model cannot “see” a person’s history in its data. In that case, it either guesses poorly or refuses to think entirely. Both outcomes can block access to jobs, courses, credit, and services—and neither situation shows up if we audit only those who received a score.

Exclusion is measurable. In face recognition, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology has long recorded demographic differences in error rates across age and sex groups; these gaps persist in real-world conditions. In speech-to-text applications, studies show higher error rates for some dialects and communities, affecting learning tools and accessibility services. In hiring, places like New York City now require bias audits for AI-assisted selection tools. However, most audits still report only pass/fail ratios for race and gender, often excluding records with “unknown” demographics. This practice can obscure exclusion behind a wall of missing data, making it crucial for stakeholders to understand the silent failures that undermine fairness and transparency.

Algorithmic exclusion in hiring and education reduces opportunity

The numbers are precise. One résumé-screening audit from January to August 2024 examined 123,610 applicant criteria and reported no formal disparate impact under the four-fifths rule. However, it also showed that 11.4% of the applicant criteria were marked “uncertain” and excluded from the analysis. Among the retained records, selection rates differed significantly: for instance, 71.5% for White applicants versus 64.4% for Asian applicants at the criterion level. Intersectional groups like Asian women had impact ratios in the mid-80s. These gaps may not reach a legal threshold, but they indicate drift. More critically, the excluded “uncertain” pool poses a risk: if the tool is more likely to be uncertain about non-linear careers, school re-entrants, or people with fragmented data, exclusion becomes a sorting mechanism that no one chose—and no one sees.

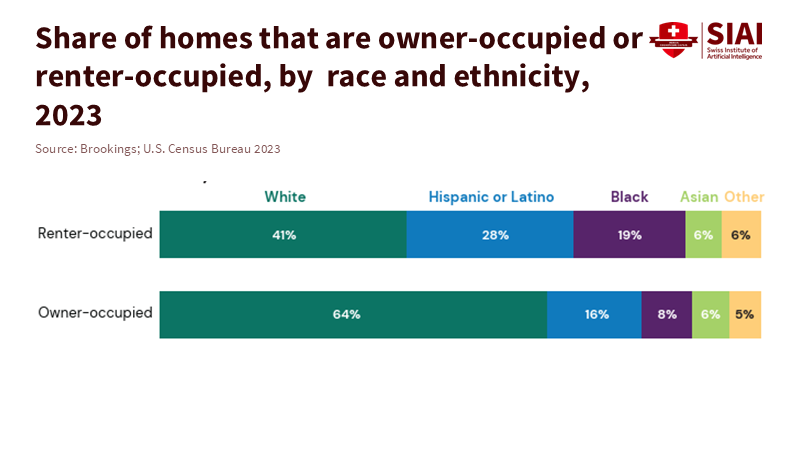

Scale amplifies the problem. A 2025 audit summary for a large matching platform listed over 9.5 million female and 11.9 million male applicants, but also recorded 60,263,080 applications with unknown race or ethnicity and more than 50 million with at least one unknown demographic field. If fairness checks depend on demographic fields, those checks become weakest where they are most needed. Meanwhile, AI in recruiting has become common: by late 2024, just over half of organizations reported using AI in recruitment, with 45% specifically using AI for résumé filtering. Exclusion at a few points in extensive talent funnels can therefore deny thousands of qualified applicants a chance to be seen by a human.

Regulators are taking action, but audits must improve transparency to reassure stakeholders that fairness is being actively monitored. The EEOC has clarified that Title VII applies to employers’ use of automated tools and highlighted the four-fifths rule for screening disparities. The OFCCP has instructed federal contractors to validate AI-assisted selection procedures and to monitor potential adverse impacts. New York City’s Local Law 144 requires annual bias audits and candidate notification. These are fundamental steps. However, if audits lack transparency about “unknown” demographics or “uncertain” outputs, exclusion remains hidden. Education systems face similar issues: silent failures in admissions, course placement, or proctoring tools can overlook learners with non-standard records. Precise, transparent measurement of who is excluded is essential for effective policy and practice.

Fixing algorithmic exclusion requires new rules for measurement and repair

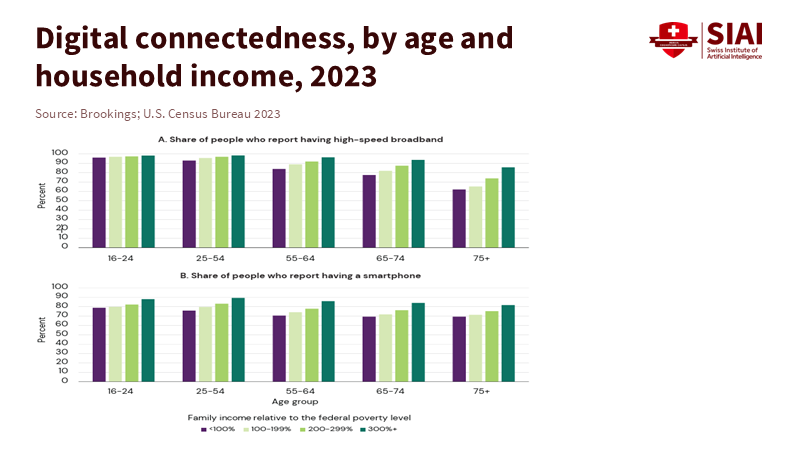

First, count silence. Any audit of AI-assisted hiring or educational tools should report the percentages of “no decision,” “uncertain,” or “not scored” outcomes by demographic segment and by critical non-demographic factors such as career breaks, school changes, or ZIP codes with limited broadband. This specific measurement approach helps stakeholders identify hidden biases. It also discourages overconfident automation: if your tool records a 10% “uncertain” rate concentrated in a few groups, having a human in the loop is not just a courtesy; it is a safety net. The Brookings proposal to formalize algorithmic exclusion as a category of harm provides regulators a tool: require “exclusion rates” in public scorecards and classify high rates as non-compliance without a remediation plan.

Second, make less-discriminatory alternatives (LDAs) the standard practice. In lending, CFPB supervision now scrutinizes AI/ML credit models, and consumer groups advocating for LDA searches argue these should be part of routine compliance. This same logic applies to hiring and education. If a ranking or filtering algorithm shows negative impacts or high exclusion rates, stakeholders should test and document an equally effective method that excludes fewer candidates. This could involve deferring to human review for edge cases, replacing rigid résumé parsing with skills-based prompts, or using structured data from standardized assignments instead of unclear proxies. Prioritizing the reduction of exclusion while ensuring job-relatedness guides organizations toward fairer AI practices.

Third, fix the code. Many real-world harms stem from ordinary defects, not complex AI math. The best estimate of the U.S. cost of poor software quality in 2022 is $2.41 trillion, with defects and technical debt as significant factors. This impacts education and HR. Flaws in data pipelines, parsing, or threshold logic can quietly eliminate qualified records. Organizations should conduct pre-deployment defect checks across both the data and decision layers, not just the model itself. Logging must ensure unscored cases are traceable. And when a coding change raises exclusion rates, it should be rolled back as we would treat security regressions. Quality assurance directly relates to fairness assurance.

What schools and employers can do now to reduce algorithmic exclusion

Educators and administrators should identify where their systems fall short in delivering results. Begin with placement and support technologies: reporting dashboards must indicate how many students the system cannot score and for whom. If remote proctoring, writing assessments, or early-alert tools have trouble with low-bandwidth connections or non-standard language varieties, prioritize routing those cases to human review. Instructors should have simple override controls and a straightforward escalation process. At the same time, capture voluntary, privacy-respecting demographic and contextual data and use it only for fairness monitoring. Suppose the “unknown” category is large. In that case, it signals a need to improve data flows, not a reason to disregard it in analysis.

Employers can take a similar approach. Require vendors to disclose exclusion rates, not just impact ratios. Refuse audits that omit unknown demographics without thorough sensitivity analysis. For high-stakes roles, set an exclusion budget—the maximum percentage of applicants who can be auto-disqualified or labeled “uncertain” without human review. Use skills-based methods and structured work samples to enlarge the data footprint for candidates with limited histories and log instances when the system cannot parse a résumé, allowing candidates to correct their records. Lastly, follow legal regulations and the direction of change: comply with New York City’s bias-audit rules, the EEOC's Title VII disparate-impact guidelines, and the OFCCP's validation expectations. This is not mere compliance; it represents a shift from one-time audits to ongoing monitoring of the areas where models often falter.

Measure the silence, rebuild the trust

The key statistic that should dominate every AI governance discussion is not only who passed or failed. It is those who were not scored—the “uncertain,” the “unknown,” the missing individuals. In 2024–2025, we learned that AI has become integral in the hiring process for most firms, even as audits reveal significant gaps in unmeasured applicants and unresolved ambiguities. These gaps are not mere technicalities. They represent lost talent, overlooked students, and eroded policy legitimacy. By treating algorithmic exclusion as a reportable harm, establishing exclusion budgets, and mandating less-exclusionary alternatives, we can keep automation fast while ensuring it is fair. This should be the guiding principle for schools and employers: ongoing measurement of silent failures, human review for edge cases, and transparent, public reporting. We do not have to wait for the perfect model. We can take action now to recognize everyone that the algorithms currently overlook.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ashby. (2024, August). Bias Audit for Ashby’s Criteria Evaluation model. FairNow.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2024, June). Fair Lending Report of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, FY 2023.

Consumer Reports & Consumer Federation of America. (2024, June). Statement on Less Discriminatory Algorithms.

Eightfold AI. (2025, March). Summary of Bias Audit Results (NYC LL 144). BABL AI.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2023). Assessing adverse impact in software, algorithms, and AI used in employment selection procedures under Title VII.

HR.com. (2024, December). Future of AI and Recruitment Technologies 2024–25.

New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. (2023). Automated Employment Decision Tools (AEDT).

NIST. (2024). Face Recognition Technology Evaluation (FRTE).

OFCCP (U.S. Department of Labor). (2024). Guidance on federal contractors’ use of AI and automated systems.

Tucker, C. (2025, December). Artificial intelligence and algorithmic exclusion. The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution.

Consortium for Information & Software Quality (CISQ). (2022). The Cost of Poor Software Quality in the U.S.

Koenecke, A., Nam, A., Lake, E., et al. (2020). Racial disparities in automated speech recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 7684–7689.