Beyond the Ban: Why AI Chip Export Controls Won’t Secure U.S. AI Leadership

Published

Modified

Export controls slow foes, not secure leadership Invest in compute, clean power, talent Make NAIRR-style Compute Commons permanent

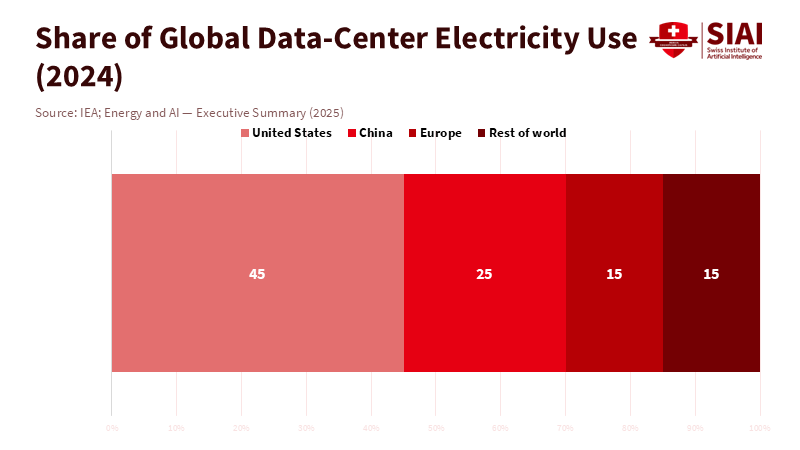

U.S. data centers used about 183 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024, roughly 4% of total U.S. power consumption. This figure is likely to more than double by 2030. The United States already accounts for 45% of global data-center electricity use. These numbers reveal a clear truth: the future of American AI relies less on what leaves our ports and more on whether we can provide the computing power, energy, and talent needed to build and use systems domestically. While AI chip export controls may seem practical, they are not the deciding factor in who leads. They can slow rivals marginally, but do not build labs, wire campuses, or train students. We must focus on transforming energy, infrastructure, and education into a self-reinforcing system. With every semester we delay, the cost of missed opportunities increases, and our advantage shrinks.

AI chip export controls are a blunt tool

Recent proposals suggest a 30-month ban on licensing top accelerators to China and other adversaries, formalizing and extending the Commerce Department’s rules. The goal is straightforward: restrict access to advanced chips and make competitors fall behind. However, the policy landscape is already complicated. In 2023 and 2024, Washington tightened regulations; in 2025, Congress discussed new “SAFE CHIPS” and “Secure and Feasible Exports” bills; and the House considered a GAIN AI Act adding certification requirements for export licenses. These measures mainly solidify what regulators are already doing. They increase compliance costs but may complicate enforcement. They could also provoke reciprocal actions abroad and push trade into unclear channels, making it harder to monitor.

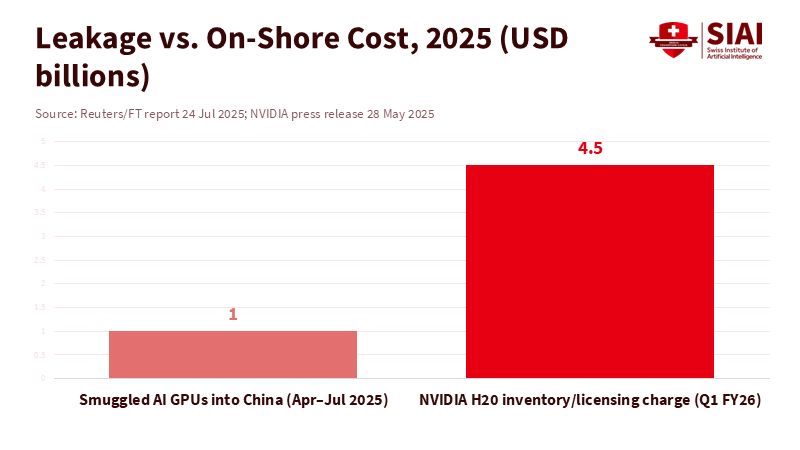

These unclear channels are real. According to a Reuters report, between April and July 2025, more than $1 billion worth of Nvidia AI chips entered China via black market channels despite strict U.S. export restrictions. Export-compliant “China-only” chips came and went as rules changed; companies wrote down their inventory; and one supplier reported no sales of its redesigned parts to China in a recent quarter after new licensing requirements were enforced. Controls produce effects, but those effects are messy, leaky, and costly domestically. In summary, AI chip export controls disappoint security advocates while imposing significant collateral damage at home.

Competition, revenue, and the U.S. innovation engine

There’s a second issue: innovation follows scale. U.S. semiconductor firms allocate a significant portion of their revenue to research and development, averaging around 18% in recent years and 17.7% in 2024. One leading AI chip company spent about $12.9 billion on R&D in 2025, despite rising sales, which lowered that percentage. That funding supports new architectures, training stacks, and tools that benefit universities and startups. A shrinking global market, as mandated by law, threatens the reinvestment cycle, particularly for suppliers and EDA tool companies that rely on the growth of system integrators.

However, supporters point out that the U.S. still commands just over 50% of global chip revenues, which they believe is strong enough to sustain industry leadership, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association. They cite record data-center revenue, long waitlists, and robust order books. All of this is true—and it underscores the argument. When companies are forced to withdraw from entire regions, they incur losses on stranded “China-only” products and experience margin pressure. Over time, these challenges affect hiring strategies, supplier decisions, and university partnerships. One research estimate shows China’s share of revenue for a key supplier dropping to single digits by late 2025; another quarter included a multi-billion-dollar write-off related to changing export rules. Innovation relies on steady cash flow and clear planning goals. AI chip export controls that fluctuate year to year do the opposite. The real question is not “ban or sell.” It’s about minimizing leakage while maintaining domestic growth.

China’s catch-up is real, but it has limits

China is making rapid progress. Domestic accelerators from Huawei and others are being shipped in volume; SMIC is increasing its advanced-node capacity; and GPU designers are eager to go public on mainland exchanges. One firm saw its stock rise by more than 400% on debut this week, thanks to supportive policies and local demand. Nevertheless, impressive performance on paper does not necessarily translate into equal capability in practice. Reports highlight issues with inter-chip connectivity, memory bandwidth, and yields; Ascend 910B production faces yield challenges around 50%, with interconnect bottlenecks being just as significant as raw performance for training large models. China can and will produce more, but its path remains uneven and costly, especially if it lacks access to cutting-edge tools. A CSIS report notes that when export controls are imposed, as seen with China, the targeted country often intensifies its own development efforts, which could lead to significant technological breakthroughs. This suggests that while export controls can increase challenges and production costs, they do not necessarily prevent a country from closing the competitive gap.

Where controls create barriers, workarounds appear. Parallel import networks connect orders through third countries; cloud access is negotiated; “semi-compliant” parts proliferate until rules change again. This ongoing dynamic strengthens China’s motivation to develop domestic substitutes. In essence, strict bans can accelerate domestic production when they are imposed without credible, consistent enforcement and without additional U.S. investments that push boundaries in a positive direction. In 2024–2025, policymakers proposed new enforcement measures, such as tamper-resistant verification and expanded “validated end-user” programs for data centers. This direction is right: smarter enforcement, fewer loopholes, and predictability, along with significant investment in American computing and power capacity for research and education.

An education-first industrial policy for AI

If the United States aims for lasting dominance, it needs a national education and computing strategy that can outpace any rival. The NAIRR pilot, initiated in 2024, demonstrated its effectiveness by providing researchers and instructors with access to shared computing and modeling resources. By 2025, it had supported hundreds of projects across nearly every state and launched a 'Classroom' track for hands-on teaching. This is more important than it may seem. Most state universities cannot afford modern AI clusters at retail prices or staff them around the clock. Shared infrastructure transforms local faculty into national contributors and provides students with practical experience with the same tools used in industry. Congress should make NAIRR permanent with multi-year funding, establish regional 'Compute Commons' driven by public universities, and link funding to inclusive training goals. According to a report from the University of Nebraska System, the National Strategic Research Institute (NSRI) has generated $35 in economic benefits for every $1 invested by the university, illustrating a strong return on investment. This impressive outcome underscores the importance of ensuring that all students in public programs can access and work with real hardware as a standard part of their education, rather than as an exception.

Computing without power is just a theory. AI demand is reshaping the power grid. U.S. computing loads accounted for about 4% of national electricity in 2024 and are projected to more than double by 2030. Commercial computing now accounts for 8% of electricity use in the commercial sector and is growing rapidly. One utility-scale deal this week included plans for multi-gigawatt campuses for cloud and social-media operators, highlighting the scale of what lies ahead. Federal and state policy should view university-adjacent power as a strategic asset: streamline connections near public campuses, create templates for long-term clean power purchase agreements that public institutions can actually sign, and prioritize transmission lines that connect "Compute Commons" to low-carbon energy sources. By aligning clean-power initiatives with campus infrastructure, we could spark the development of regional tech clusters. This would not only enhance educational capabilities but also attract industry partners eager to capitalize on a well-connected talent pool. The talent-energy feedback loop becomes essential, creating synergies that can broaden support far beyond energy committees. When AI chip export controls dominate the discussion, this vital bottleneck is often overlooked. Yet it determines who can teach, who can engage in open-science AI, and who can graduate students with real-world experience using production-grade systems.

Leadership is created, not blocked. It thrives in labs, on the grid, and within public universities, preparing the next generation of innovators. To ensure continued progress and maintain our competitive edge, we must embrace policies that amplify our strengths while fostering innovation. It is critical to envision and reach the next policy milestone that inspires collective action and drives us toward a future where American leadership in AI is unassailable.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bloomberg. (2025, Dec. 4). Senators Seek to Block Nvidia From Selling Top AI Chips to China.

Bloomberg

Brookings Institution. (2025, Dec. 3). Why the GAIN AI Act would undermine US AI preeminence.

Brookings

CSET (Georgetown). (2024, May 8). The NAIRR Pilot: Estimating Compute.

CSIS. (2024, Dec. 11). Understanding the Biden Administration’s Updated Export Controls.

CSIS. (2025, Nov. 6). The Architecture of AI Leadership: Enforcement, Innovation, and Global Trust.

ExecutiveGov. (2025, Dec.). Bipartisan House Bill Seeks to Strengthen Enforcement of AI Chip Export Controls.

Financial Times. (2025, Dec.). Chinese challenger to Nvidia surges 425% in market debut.

Financial Times via Reuters summary. (2025, Jul. 24). Nvidia AI chips worth $1 billion entered China despite U.S. curbs.

IEA. (2024, Jan. 24). Electricity 2024.

IEA. (2025, Apr. 10). Global data centre electricity consumption, 2020–2030 and Share by region, 2024.

IEA. (2025). Energy and AI: Energy demand from AI and Executive Summary.

MERICS. (2025, Mar. 20). Despite Huawei’s progress, Nvidia continues to dominate China’s AI chips market.

NVIDIA. (2025, Feb. 26). Financial Results for Q4 and Fiscal 2025.

NVIDIA. (2025, May 28). Financial Results for Q1 Fiscal 2026. (H20 licensing charge.)

NVIDIA. (2025, Aug. 27). Financial Results for Q2 Fiscal 2026. (No H20 sales to China in quarter.)

Pew Research Center. (2025, Oct. 24). What we know about energy use at U.S. data centers amid the AI boom.

Reuters. (2025, Dec. 8). NextEra expands Google Cloud partnership, secures clean energy contracts with Meta.

Reuters. (2025, Dec. 4). Senators unveil bill to keep Trump from easing curbs on AI chip sales to China.

Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). (2025, Jul.). State of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry Report 2025.

SemiAnalysis. (2025, Sep. 8). Huawei Ascend production ramp. (SMIC capacity estimates.)

The Information (archived via SOPA). (2024, Aug. 12). Nvidia AI chip smuggling to China becomes an industry.

Tom’s Hardware. (2025, Jul. 25). Underground China repair shops thrive servicing illicit Nvidia GPUs.

Tom’s Hardware. (2025, Dec.). Nvidia lobbies White House… lawmakers reportedly reject GAIN AI Act.

U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS). (2025, Jan. 15). Federal Register notice on Data Center Validated End-User program.

U.S. EIA. (2025, Jun. 25). Electricity use for commercial computing could surpass other uses by 2050.

The Wall Street Journal, LA Times, and other contemporaneous reporting on lobbying dynamics (cross-checked for consistency).

Comment