The New Literacy of War: Why Defense AI Education Must Move Faster Than the Drones

Published

Modified

Defense AI education is the bottleneck between record defense spending and real capability Train stack-aware teams with mission credentials Scale safely with oversight and shared compute

In 2024, global military spending soared to $2.718 trillion, the most significant annual rise since the Cold War. Simultaneously, Ukraine's frontline units lost 10,000 drones each month. This marks a shift in warfare from bodies to machines. Together, these facts highlight a critical issue: we do not educate enough people to direct, manage, and improve the software that now controls the pace and reach in the field and across defense agencies. Procurement budgets are racing ahead, while practice is falling behind. “Defense AI education” represents the gap between money and real outcomes—the difference between countless systems and genuine advantage. It now determines how fast ministries learn from battlefield data, how quickly logisticians adapt policies, and whether future officers can manage drone swarms as confidently as past leaders handled platoons. If we fail to teach and credential on a large scale, the drones will operate independently, unethically, and without impact.

Defense AI Education Is Now the Bottleneck

The past two years have driven this point home. NATO’s European members and Canada boosted defense spending by 18% in 2024. Twenty-three allies hit the 2% GDP target, more than double the number four years ago. Europe is urgently launching new industrial programs under EDIS and EDIP to push funds toward production and joint procurement. But time is running out: money alone will not deliver strategic gains. Training pathways, credentialing standards, and access to computing resources now determine whether AI tools can impact operations before the pace of threats accelerates further. That is what we must define as defense AI education: not just courses but rapid training to transform procurement, maintenance, planning, and policy toward faster, safer, and more accurate decisions. Note: the NATO figures reflect official ally submissions; EDIS/EDIP documents are legislative and program materials, not survey estimates.

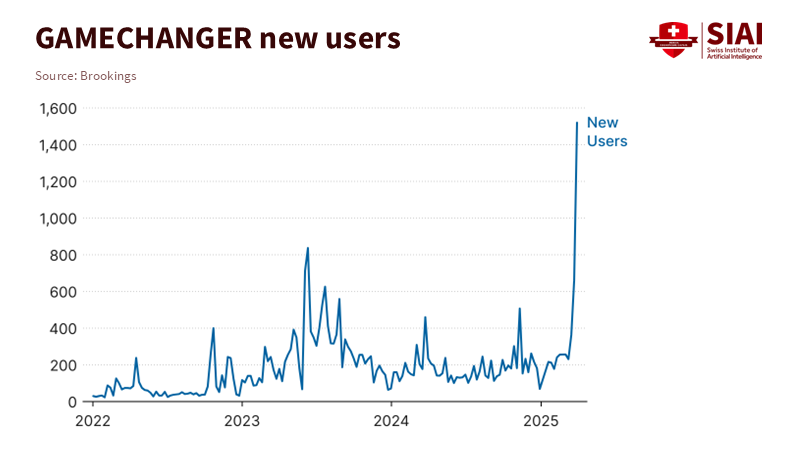

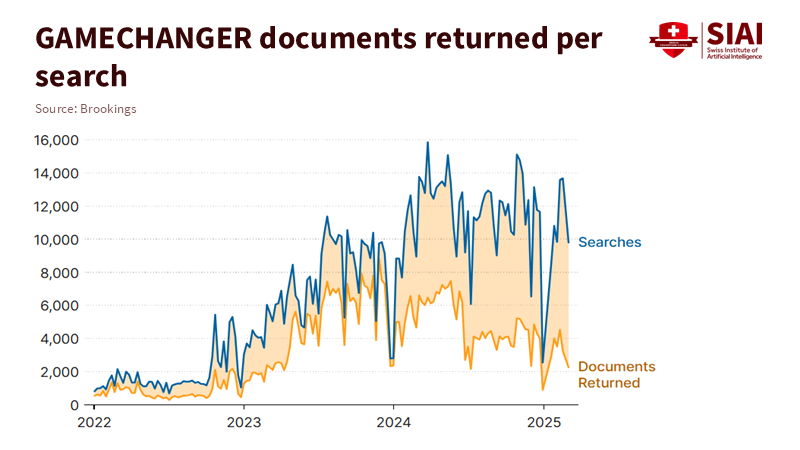

We already have a proof of concept in the U.S. Department of Defense. According to Brookings, GAMECHANGER is an AI-enabled search and association platform for policy that was developed to process unclassified policy documents and improve the management of complex directives and authorities. The lesson here is not that one tool can solve all problems. Instead, enterprise AI adoption increases when users can find, test, and tailor software for specific tasks, then apply that knowledge in the future. A report from the Brookings Institution discusses the importance of addressing workforce challenges and modernizing education in national security fields, emphasizing the need for effective recruitment, retention, and up-to-date training to prepare for emerging technologies such as AI. Teach policy staff how to question models. Teach program managers how to assess task-level value. Teach leaders to maintain tools through rotations. Note: usage numbers and institutional details are from the Brookings analysis; the scope is non-classified and focused on the enterprise side.

Defense AI Education for the Drone Age

The battlefield is already teeming with affordable autonomous systems. RUSI reports that Ukraine loses 10,000 drones per month, largely to electronic warfare—an urgent sign that success relies on learning, adapting, and replenishing at scale, not on a single advanced platform. U.S. policy has responded with haste: the Replicator initiative aims to deploy “thousands of autonomous systems” across all domains within the next 18 to 24 months. Funding, experimentation, and transition updates will come fast through late 2024. Europe’s industrial surge under EDIS and EDIP likewise calls for immediate mass production and speed. Defense AI education must not wait; it is the critical link that connects swarm tactics, resilient communications, electronic warfare-aware autonomy, and agile teamwork between humans and machines. Note: drone loss data comes from RUSI’s open-source report; Replicator details are based on official DoD announcements and analyses.

This training must reach beyond operators. The key advantage lies with “stack-aware” talent—people who understand sensors, data links, model behavior, and mission outcomes as a cohesive unit. Industry evidence supports this view. BCG estimates the aerospace and defense sector spent about $26.6 billion on AI in 2024, roughly 3% of its revenue. Yet 65% of programs remain stuck in the proof-of-concept stage. Value emerges when user-friendly solutions, domain-tailored models, and redesigned workflows come first—not yet another data pool. To translate this into curricula, it means creating capstone projects that assess mission-based return on investment rather than just model accuracy. It also means teaching students to work with electronic warfare-decoyed data, degraded GPS signals, or high-latency environments. Note: the spending and maturity estimates are from BCG’s 2025 sector report and accompanying PDF; these figures are based on surveys and modeling.

A Curriculum Playbook for Scale

Defense AI education should shift from specialized fellowships to widespread programs with quick time-to-value. First, establish mission studios that reflect real industry tasks. Pair an air base logistics dataset with a policy graph, and ask students to create prompts and agents that reduce parts approval time while adhering to ethical and legal guidelines. According to Purdue University, the Anvil supercomputer joined the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) Pilot in May, providing expanded access to advanced computing power. Adopting successful methods like GAMECHANGER and integrating NAIRR resources could allow public universities without extensive infrastructure to conduct multi-GPU experiments and improve machine learning operations education, potentially benefiting fields such as finance, healthcare, and maintenance in realistic conditions. According to the U.S. National Science Foundation, efforts to expand access to AI resources through the NAIRR pilot are strengthened by collaboration with organizations like Voltage Park; building on this momentum, there is a growing push to establish a standardized and trusted system of credentials that ranges from foundational micro-credentials for operators to advanced leadership residencies. Link each credential to mission-based test events so learning directly supports deployment needs. Leverage European and NATO programs to coordinate and standardize, and use resources like NAIRR to ensure access is affordable and widespread. The goal: make education actionable, efficient, and directly connected to defense priorities.

Anticipating Critiques—and Meeting Them

To address the moral concern that defense AI education could militarize universities, take these actions: require safety cases and ethics reviews, implement export-control education, and separate research focused on lethal applications from that aimed at enterprise performance or humanitarian protection. Also, make curricula and assessment criteria public. These safeguards create transparent processes and oversight, supporting responsible AI adoption in defense.

The economic critique—why train for AI at scale if organizations cannot absorb it—demands three steps: teach practical adoption ("absorption") in courses, focus on user-friendly solutions beyond technical models, and evaluate students on their ability to drive operational change and return on investment. Capstone projects should deliver measurable outcomes—reduced policy alignment time, fewer false alarms, and less maintenance downtime. Making value visible prompts leaders to invest in talent and projects that advance organizational goals.

To address the talent supply concern, implement three key recommendations: expand the recruiting pool through apprenticeships and flexible pay, create crossover programs for educators in math and computing, and define clear roles for AI-focused jobs, such as product owners, data engineers, safety testers, and mission designers. This will help meet urgent demand and broaden access to high-priority defense roles.

A final concern is strategic: Europe’s increase in defense spending may stem more from geopolitical anxiety than from a coherent strategy. This is true, and that’s why education must be the priority. NATO’s spending increases and the EU’s industrial strategy create an opportunity to standardize training, evaluation, and data sharing, ensuring coalitions can work together seamlessly. Shared syllabi, common credentials, and NAIRR-like computing partnerships can prevent a mix of incompatible tools. If we teach to a common standard now, the next crisis won’t force us to rebuild skills while under pressure. Note: NATO statements are official records; the EU roadmap is a Commission document; computing partnerships refer to NAIRR designs.

From Spending to Understanding

The numbers that began this essay should capture our attention. $2.718 trillion in global military spending. Drone losses in the tens of thousands each month on one front. These figures describe a world where software dictates pace, and where disruption, jamming, and losses penalize those who cannot learn quickly. The challenge for universities, ministries, and industry is whether education itself can expand. Defense AI education is how we make this shift—from purchasing to understanding, from pilots to practical application, from hype to real value. It involves more than just courses. It requires credentials linked to missions, computing resources reaching both provinces and capitals, and leadership training that views governance as a skill, not just paperwork. If we align budgets, programs, and standards now, we can transform quantity into quality and risk into resilience. If we do not, we will spend more and comprehend less—and see the gap widen with every flight hour and every update cycle. The choice is ours, and time is not on our side.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Boston Consulting Group. (2025). Three Truths About AI in Aerospace and Defense (report and PDF). Retrieved June 2025.

Brookings Institution. (2025, Dec. 1). GAMECHANGER: A case study of AI innovation at the Department of Defense.

European Commission. (2025, Nov. 19). EU Defence Industry Transformation Roadmap.

European Commission. (2024). European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) and EDIP overview.

NATO. (2024, June 17–18). Remarks and joint press conference transcripts.

National Science Foundation (NSF). (2024). NAIRR Pilot announcements and resource access.

RUSI. (2023). Russia and Ukraine are filling the sky with drones (drone loss estimates).

SIPRI. (2025, Apr. 28). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024 (press release and fact sheet).

U.S. Department of Defense / DIU. (2023–2024). Replicator initiative overview and updates.

U.S. DoD / CDAO. (2024). Task Force Lima executive summary (public release).

U.S. Government reporting. (2024). Cyber workforce vacancy updates.

Comment