Beyond the Hype: Causal AI in Education Needs a Spurious Regression Check

Published

Modified

AI in education is pattern matching, not true thinking The danger is confusing correlation with real causal insight Schools must demand causal evidence before using AI in high-stakes decisions

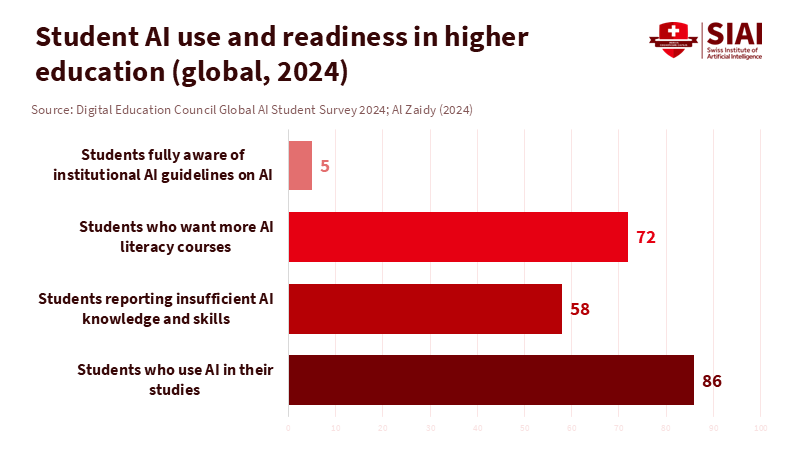

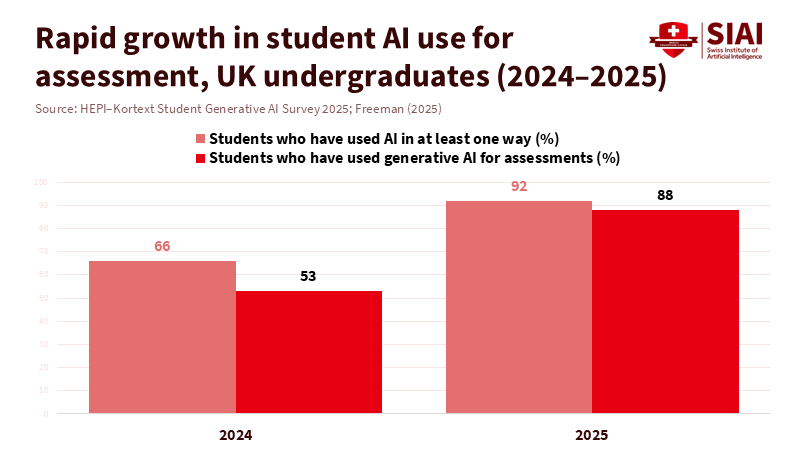

In 2025, a national survey in the United Kingdom found that 88% of university students were using generative AI tools like ChatGPT for their assessments. However, a global UNESCO survey of over 450 schools and universities found that fewer than 10 percent provided any formal guidance on the use of AI in teaching and learning. This shows that causal AI in education is growing from the ground up. At the same time, institutions debate the nature of these systems. Many public figures suggest each new model brings us closer to 'human-level' thinking. In reality, classrooms are using basic tools. Students depend on powerful pattern machines that don't truly grasp cause and effect. Education policy must recognize this before effectively using causal AI in education, emphasizing policies that promote understanding of causal relationships rather than superficial pattern-matching.

Causal AI in Education: Why Pattern Matching Is Not Intelligence

Much of the current debate assumes AI is steadily advancing towards general intelligence. When a system writes an essay or solves a math problem, some people claim the benchmarks for intelligence have shifted. This perspective overlooks what today's systems actually accomplish. They are massive engines for statistical pattern matching. They learn from trillions of words and images, identifying which tokens typically connect to others. If we define intelligence as the ability to create causal models, operate across various domains, and learn from experience, the situation looks different. These systems do not resemble self-learning agents, such as children or animals. In econometrics, this shallow connection between variables is known as spurious regression. Two lines may move in tandem, the model shows a high score, yet nothing indicates that one causes the other. That is what most generative models offer in classrooms today. They make predictions and imitate actions without understanding why. Industry professionals observe the same trend: systems excel at identifying correlations in large datasets, but humans must determine whether those signals reflect actual causal forces.

Recent evidence from technical evaluations supports this. The 2025 AI Index report indicates that while cutting-edge models now match or surpass humans on many benchmark tests, they still struggle with complex reasoning tasks like planning and logic puzzles, even when exact solutions exist. In other words, they perform well when the problem resembles their training data but fail when faced with fresh causal structures. Studies on large reasoning models from major labs tell a similar story. Performance declines as tasks become more complex, and models often resort to shortcuts rather than thinking harder. Additional work shows that top chatbots achieve high accuracy on factual questions, yet still confuse belief with fact and treat surface patterns as explanations. These are clear signs of spurious regression, not signs of minds awakening. This distinction is crucial for causal AI in education.

Spurious Regression, AGI Hype, and Causal AI in Education

Spurious regression isn't just a technical term; it reflects a common human tendency. When two trends move together over time, people want to create a narrative linking them. Economists learn to approach this impulse with caution. For instance, two countries might see rising exports and internet usage simultaneously. That doesn’t mean that browsing the web causes trade surpluses. Similarly, when a model mimics human style, passes exams, and engages in fluent conversations, people often interpret it as a sign of a thinking agent. However, what’s actually happening is more like a significant auto-complete function. The system selects tokens that fit the statistical pattern. It doesn't account for what would happen if a curriculum changed, an experiment were conducted, or a rule were broken. It lacks an innate sense of intervention. This is why causal AI in education is significant; it emphasizes what causes real-world changes rather than just what predicts the next word.

The public already senses something is amiss. Surveys indicate that just over half of adults in the United States feel more anxious than excited about AI in everyday life, with only a slight percentage feeling mostly excited. At the same time, adoption in education is rapidly advancing. A 2024 global survey found that 86% of higher education students used AI tools in their studies, with most using them weekly or more. By 2025, a survey in the United Kingdom found that 88 percent of students used generative AI tools for assessments, and more than nine in ten used AI for some academic work. Yet the same surveys showed that about half of students did not feel "AI-ready" and lacked confidence in their ability to use these tools effectively. Meanwhile, UNESCO found that fewer than one in ten institutions had formal AI policies in place. This context highlights the challenges for causal AI in education: heavy usage, minimal guidance, and significant concern.

Other sectors are beginning to correct similar issues by adopting causal methods. Healthcare serves as a helpful example. For years, clinical teams relied on machine learning models that ranked patients by risk. These systems were effective at identifying patterns, such as the connection between specific lab results and future complications. Still, they could not show what would happen if a treatment changed. New developments in causal AI for drug trials and care pathways aim to address this gap. They create models that ask 'what if ' questions and employ rigorous experimental or quasi-experimental designs to distinguish genuine drivers from misleading correlations. The goal isn’t to make models seem more human but to ensure their recommendations are safer and more reliable when circumstances change. Educational policy should incorporate these insights by supporting research that develops causal models capable of predicting the impact of interventions, thus ensuring AI tools in education are both effective and trustworthy in dynamic classroom environments.

Policy Priorities for Causal AI in Education

The priority is to teach the next generation what these systems can and cannot do. Currently, students see attractive interfaces and smooth language and assume there’s a mind behind the screen. Yet research tells a different story. Large language models can solve Olympiad-level math problems and produce plausible step-by-step reasoning. However, independent evaluations reveal they still struggle with many logic tasks, lose track of constraints, and cannot reliably plan over multiple steps. When tasks become more challenging, models often guess quickly instead of thinking more deeply. In classroom settings, this means AI will excel at drafting, summarizing, and spotting patterns but will fall short when asked to justify a causal claim. Educators can turn this into a valuable teaching moment. Causal AI in education should emphasize critical use of current tools by encouraging students to question model answers for hidden assumptions, missing mechanisms, and spurious regression.

The second priority is institutional. AI literacy shouldn't rely solely on individual teachers. Parents and students expect schools to take action. Recent surveys in the United States show that nearly 9 in 10 parents believe knowledge of AI is crucial for their children’s education and career success, and about 2/3 think schools should explicitly teach students how to use AI. Yet UNESCO's survey indicates that fewer than ten percent of institutions provide formal guidance. Many universities rely on ad hoc policies crafted by small committees under time pressure. This mismatch invites both overreaction and negligence. One extreme leads to blanket bans that push AI use underground and hinder honest discussion. The other leads to blind trust in "AI tutors" taking charge of feedback and assessment. A policy agenda focused on causal AI in education should ask a straightforward question: under what conditions does a specific AI tool noticeably help students learn, and how do those effects vary for different groups?

Answering that question requires better evidence. The tools of causal AI in education are practical, straightforward methods that many institutions already use in other areas. Randomized trials can compare sections using an AI writing assistant to those that do not, tracking not only grades but also the transfer of skills to new tasks. Quasi-experimental designs can study the impact of AI-enabled homework support in districts that introduce new tools in phased implementations. Learning analytics teams can shift from dashboards that merely describe past behavior to models that simulate the consequences of changes in grading rules or feedback styles. None of this necessitates systems that think like humans; it requires clarity about causes and careful control groups. The potential benefits are considerable. Rather than debating abstractly whether AI is "good" or "bad" for learning, institutions can begin to identify where causal AI in education truly adds value and where it merely automates spurious regression.

The final priority is to establish regulatory clarity. Governments are rapidly addressing AI in general, but education often remains on the sidelines of those discussions. Regulations that treat all advanced models as steps toward general intelligence can overlook the real risks. In education, the most urgent dangers arise from pattern-matching systems that appear authoritative while concealing their limitations. Recent technical studies show that even leading chatbots released after mid-2024 still struggle to distinguish fact from belief and can confidently present incorrect explanations in sensitive areas such as law and medicine. Other research highlights a significant drop in accuracy when reasoning models tackle more complex challenges, even though they perform well on simpler tasks. These are not minor issues on the path to human-like thought; they signal the risks of relying too heavily on correlation. Regulations shaped by causal AI in education should mandate that any high-stakes use, such as grading or placement, undergo experimental testing for robustness to change, rather than relying solely on benchmark scores based on past data.

Education systems face a critical choice. One path tells a story where every new AI breakthrough prompts us to redefine intelligence and brings us closer to machines that think like us. The other path presents a more realistic view. In this perspective, today’s systems are fast, cost-effective engines for statistical fitting that can benefit classrooms when used responsibly. They can also cause serious issues if we confuse spurious regression with genuine understanding. The statistics presented at the beginning should draw attention. When nearly 90% of students depend on AI for their work, and fewer than 10% of institutions provide solid guidance, the problem isn't that machines are becoming too intelligent. Instead, the issue is that policy isn't smart enough about machines. The task ahead is straightforward. Foster a culture of causal AI in education that encourages students to question patterns, empowers teachers to conduct simple experiments, and insists on evidence before high-stakes deployment. If we succeed, the goalposts do not need to shift at all.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

College Board. (2025). U.S. high school students’ use of generative artificial intelligence. Research Brief.

DIA Global Forum. (2024). Correlation vs. causation: How causal AI is helping determine key connections in healthcare and clinical trials.

Digital Education Council. (2024). Key results from DEC Global AI Student Survey 2024.

Higher Education Policy Institute. (2025). Student generative AI survey 2025.

Pew Research Center. (2023). What the data says about Americans’ views of artificial intelligence.

Qymatix. (2025). Correlation and causality in artificial intelligence: What does this mean for wholesalers?

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. (2025). AI Index Report 2025.

UNESCO. (2023). Guidance for generative AI in education and research: Executive summary.

Comment