Governing at Machine Speed: How to Prevent AI Bank Runs from Becoming the Next Crisis

Published

Modified

AI is accelerating bank-run risk into “AI bank runs” Supervisors lag far behind banks in AI tools and skills We need real-time oversight, automated crisis tools, and targeted training now

In March 2023, a mid-sized American bank experienced a day when depositors attempted to withdraw $42 billion. Most of this rush came from simple phone taps, not from long lines outside the bank. Although this scramble did not yet use fully autonomous systems, it demonstrated how quickly fear can spread when money moves as fast as a push notification. Now, imagine an added layer. Corporate treasurers use AI tools to track every rumor. Households rely on chatbots that adjust savings in real time. Trading engines react to each other's moves in milliseconds. The outcome is not a traditional bank run. Instead, it’s the potential for AI-driven bank runs, in which algorithms trigger, amplify, and execute waves of withdrawals and funding cuts long before human supervisors can act.

Why AI Bank Runs Change the Crisis Playbook

Systemic banking crises have always involved everyone rushing for the same exit at the same time. In the past, this coordination relied on rumors, news broadcasts, and human analysis of financial reports spread over hours or days. Today, AI systems can scan markets, social media, and private data streams in seconds. They update risk models and send orders almost immediately. The rush that caused Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse was one example. Customers attempted to withdraw tens of billions of dollars in a single day, highlighting the power of digital channels and online coordination. Future AI bank runs will shorten that timeline even more. Automated systems will learn to respond not only to general news but also to each other’s activities in markets and payment flows. Tools that smooth out minor fluctuations during calm periods can trigger sudden, synchronized movements during stressful periods.

The groundwork for AI bank runs is already established. In developing economies, the percentage of adults making or receiving digital payments grew from 35 percent in 2014 to 57 percent in 2021. In high-income economies, this percentage is nearly universal. Recent Global Findex updates show that 42 percent of adults made a digital payment to a merchant in 2024, up from 35 percent in 2021. At the same time, 86 percent of adults worldwide now own a mobile phone, and 68 percent have a smartphone. On the supply side, surveys conducted by European and national authorities indicate that a clear majority of banks currently use AI for tasks like credit scoring, fraud detection, and trading. This means that the technical ability for AI bank runs is in place today. Highly digital customers, near-instant payments, and widespread AI use among firms are all established. What is lacking is a supervisory framework that can monitor and influence these dynamics before they develop into full-blown crises.

What Emerging Markets Teach Us about AI Bank Runs

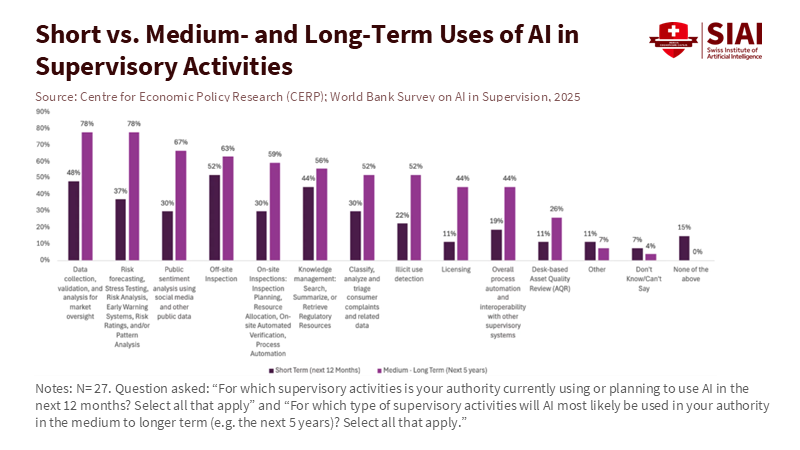

The weakest link in this situation is not the sophistication of private sector tools but the readiness of supervisory agencies. A recent survey of 27 financial sector authorities in emerging markets and developing economies shows that most anticipate AI will have a net positive effect. Yet their own use of AI for supervision remains limited. Many authorities are still in pilot mode for essential tasks such as data collection, anomaly detection, and off-site monitoring. Only about a quarter have formal internal policies on AI use. In parts of Africa, the percentage is even lower. The usual barriers are present. Data is often fragmented or incomplete. IT systems may be unreliable. Staff with the right technical skills are scarce. Concerns about data privacy, sovereignty, and vendor risk add further complications. Supervisors face the threat of AI bank runs with inadequate tools, incomplete data, and insufficient personnel.

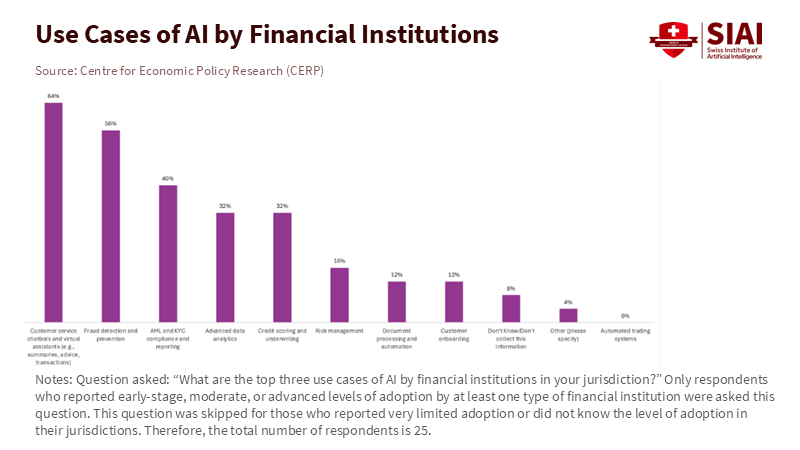

In contrast, financial institutions in these same regions are advancing more quickly. The survey reveals that where AI is implemented, banks and firms focus on customer service chatbots, fraud detection, and anti-money laundering checks. African institutions are more inclined to use AI for credit scoring and underwriting in markets with limited data. These applications may seem low risk compared to high-frequency trading. However, they can create new pathways for a sudden loss of trust. A failure in an AI fraud detection system can freeze thousands of accounts simultaneously. A flawed credit model can halt lending in entire sectors overnight. The Financial Stability Board has noted that many authorities, including those in advanced economies, struggle to monitor AI-related vulnerabilities using current data-collection methods. Therefore, emerging markets serve as an early warning system. They illustrate how quickly a gap can widen between supervised firms and supervisory agencies. They also show how that gap can evolve into a serious vulnerability if not treated as an essential issue.

Designing Concrete Defenses against AI Bank Runs

If AI bank runs pose a structural risk, then mere "AI-aware supervision" is insufficient. Authorities need a solid framework for prevention and response. The first building block is straightforward but often overlooked. Supervisors need real-time insight into where AI is used within large firms. Some authorities have begun asking banks to disclose whether they use AI in areas such as risk management, credit, and treasury. The results are inconsistent and hard to compare. A more serious method would treat high-impact AI systems like vital infrastructure. Banks would maintain a live register of models that influence liquidity management, deposit pricing, collateral valuation, and payment routing. This register should include key vendors and data sources. Supervisors could then see where similar models or vendors are used across institutions and where synchronized actions might occur under stress. This step is essential for any coherent response to AI bank runs.

The second building block is shared early warning systems that reflect, at least partially, the speed and complexity of private algorithms. Some central banks already conduct interactive stress tests in which firms adapt their strategies as conditions change. Groups of authorities could build on this idea and use methods such as federated learning to jointly train models on local data without sharing raw data. These supervisory models would monitor not just traditional indicators but also the behavior of high-impact AI systems across banks, payment providers, and large non-bank platforms. Signals from these models, combined with insights about vendor concentration, would enable authorities to detect when AI bank runs are developing. They wouldn’t simply observe deposit outflows after the fact.

The third building block is crisis infrastructure that can act quickly when early warnings appear. Authorities already use tools such as market circuit breakers and standing liquidity facilities. For AI bank runs, these tools must be redesigned with automated triggers. This could mean pre-authorized liquidity lines that activate when particular patterns of outflows are detected across multiple institutions. It might involve temporary restrictions on certain types of algorithmic orders or instant transfer products during extreme stress. None of this eliminates the need for human judgment. It simply acknowledges that by the time a crisis committee gathers, AI-driven actions may have already changed balance sheets. Without pre-set responses linked to well-defined metrics, supervisors will remain bystanders in events they should oversee.

An Education Agenda for an Era of AI Bank Runs

These defenses will be ineffective if they rely on a small group of technical experts. The survey of emerging markets highlights that internal skill shortages are a significant obstacle to the use of AI in supervision. This issue is also prevalent in many advanced economies, where central bank staff and frontline supervisors often lack practical experience with modern machine learning tools. At the same time, most adults now carry smartphones, send digital payments, and interact with AI-powered systems in their daily lives. The human bottleneck lies within the authorities, not beyond them. Bridging that gap is therefore as much an educational challenge as it is a regulatory one. It requires a new collaboration between financial authorities, universities, and online training providers.

That collaboration should start with the reality of AI bank runs, not with vague courses on "innovation." Supervisors, policymakers, and bank risk teams need access to practical programs. These should blend basic coding and data literacy with a solid understanding of liquidity risk, market dynamics, and consumer behavior in digital settings. Scenario labs where participants simulate AI bank runs can be more effective than traditional lectures for building intuition. In these exercises, chatbots, robo-advisers, treasurers, and central bank tools all interact on the same screen. Micro-credentials for board members, regulators, and journalists can spread that knowledge beyond just a small group of experts. Online education platforms can make these resources available to authorities in low-income countries that can’t afford large in-house training programs. The goal isn’t to turn every supervisor into a data scientist. It is to ensure that enough people in the system understand what an AI bank looks like in practice. Only then can the institutional response be informed, swift, and coordinated.

The window to act is still open. The same global surveys that indicate rapid adoption of AI in banks also show that supervisors’ use of AI remains at an earlier stage. The gap is vast in emerging markets. Today’s digital bank runs, like the surge that caused a mid-sized lender to collapse in 2023, still unfold over hours instead of seconds. However, that margin is decreasing as AI transitions from test projects to essential systems in both finance and everyday life. Authorities can still alter their path. Investments in data infrastructure, shared supervisory models, machine-speed crisis tools, and a serious education agenda can prevent AI bank runs from becoming the major crises of the next decade. If they hesitate, the next systemic event may not begin with a rumor in a line. It may start with a silent cascade of algorithm-driven decisions that no one in charge can detect or understand.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank of England. 2024. Artificial intelligence in UK financial services 2024. London: Bank of England.

Boeddu, Gian, Erik Feyen, Sergio Jose de Mesquita Gomes, Serafin Martinez Jaramillo, Arpita Sarkar, Srishti Sinha, Yasemin Palta, and Alexandra Gutiérrez Traverso. 2025. “AI for financial sector supervision: New evidence from emerging market and developing economies.” VoxEU, 18 November.

Danielsson, Jon. 2025. “How financial authorities best respond to AI challenges.” VoxEU, 25 November.

European Central Bank. 2024. “The rise of artificial intelligence: benefits and risks for financial stability.” Financial Stability Review, May.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. 2023. “Recent bank failures and the federal regulatory response.” Speech by Chairman Martin J. Gruenberg, 27 March.

Financial Stability Board. 2025. Monitoring adoption of artificial intelligence and related technologies. Basel: FSB.

Financial Times. 2024. “Banks’ use of AI could be included in stress tests, says Bank of England deputy governor.” 6 November.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute. 2025. “World Bank Global Findex 2025 insight.” 9 October.

World Bank. 2022. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2025a. “Mobile-phone technology powers saving surge in developing economies.” Press release, 16 July.

World Bank. 2025b. Artificial Intelligence for Financial Sector Supervision: An Emerging Market and Developing Economies Perspective. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Comment