Sovereign AI Is Becoming Public Infrastructure

Published

Modified

Sovereign AI is public infrastructure for education Countries blend open models and public compute to localize and cut dependence Schools need shared data, transparent tests, and energy-smart procurement

In late 2025, South Korea announced plans with NVIDIA and local companies to deploy more than 260,000 GPUs across 'sovereign clouds' and AI factories. This figure shows a shift in ambition. It’s not just a pilot project; it is a national infrastructure. Europe is also taking similar steps. They are expanding a network of public 'AI Factories' based on EuroHPC supercomputers. This will allow startups and universities to access the substantial computing power needed for large models at a reduced cost. In Latin America, a regional team is training Latam-GPT to reflect local laws, languages, and cultures, rather than relying on defaults from Silicon Valley. The common goal is clear. Countries want their education systems, courts, and public services to depend on models they own and can examine. They seek sovereign AI systems that align with local laws, culture, security, and education needs—so that teachers and students can trust what they use.

The case for sovereign AI

Sovereign AI is more than just a slogan. It represents a shift from purchasing general cloud services to creating controllable AI systems governed by local rules. Switzerland has demonstrated that a high-income democracy can achieve this openly. In September, ETH Zurich, EPFL, and the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre introduced Apertus, an open, multilingual model trained on public infrastructure and available for broad use. The team presents it as a model for transparent, sovereign foundations that others can adapt. Openness is a policy choice, not just a marketing strategy. It increases accountability and enables schools, ministries, and researchers to verify claims rather than accept black boxes, which is crucial for strategic decision-making and public trust.

Sovereign AI is also necessary where global models do not fit local needs. The collaborative effort behind Latam-GPT, led by Chile’s CENIA, is training the model on regional legal texts, educational materials, and public records to represent Spanish, Portuguese, and Indigenous languages accurately. This approach is not just for show. When models struggle with code-switching or regional expressions, they can make classroom use risky and civic interactions unfair. A regional base model with national adjustments can bridge that gap. The goal is not to outperform the largest U.S. model on English benchmarks; it is to provide answers, grading, and guidance in the language and context students are familiar with.

Build, borrow, or blend: a sovereign AI playbook

There are three main routes to implement sovereign AI. The first is to build from the ground up, as Switzerland has done. The advantage is control over data, training methods, safety measures, and licensing. However, this approach is costly, requiring ongoing public funding, a consistent talent pool, and long-term computing resources. The second option is to borrow and adapt. Latin America’s initiative illustrates a low-compute option: start with an open-weight model and use adapters or LoRA to tailor it for slang, public services, and curricula. This can be done in weeks on modest clusters, which is essential for education budgets. The third option is to blend. This involves anchoring public policy in open models, contracting for private resources when necessary, and forming collaborations to reduce costs.

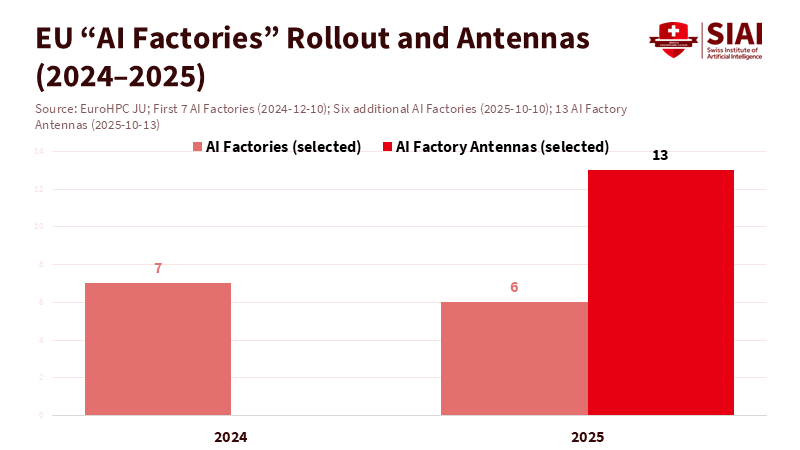

Europe's blended approach is currently the most advanced. The EU's AI Factories initiative leverages EuroHPC to provide AI-optimized supercomputing resources to startups, universities, and small- and medium-sized enterprises. The first wave of seven sites launched after 2024, with six more selected in October 2025, alongside new "AI Factory Antennas" to expand access. Funding is a mix of EU programs and national contributions. The policy goal is straightforward: reduce reliance on foreign, closed models by creating sovereign AI capacity as a shared resource. In the private sector, Europe’s Mistral continues to release strong open-weight models, enhancing the link between public infrastructure and open tools. This exemplifies a “borrow and blend” strategy on a continental scale.

Power, chips, and classrooms: the hidden costs of sovereign AI

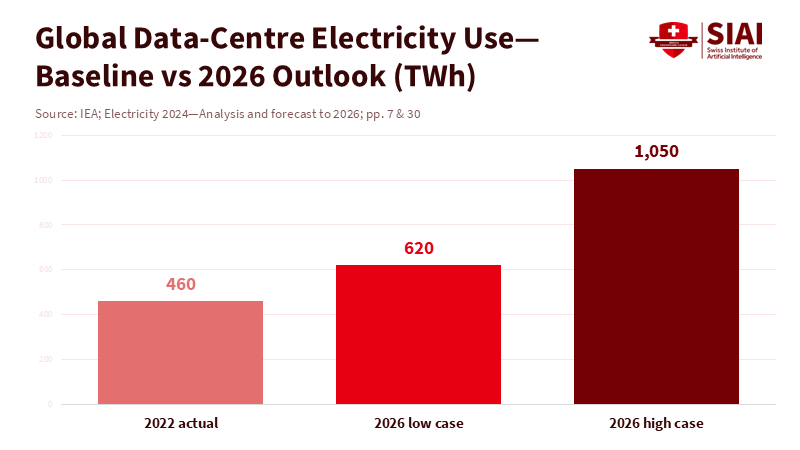

Sovereign AI requires significant computing and energy resources. The International Energy Agency expects global data center energy consumption to more than double by 2030, reaching about 945 TWh, with AI-focused centers contributing a large share of this increase. Education planners need to view this figure as both a budget item and a constraint on energy supply. Suppose a ministry wants an AI tutor in every classroom. In that case, it must consider where processing occurs, who pays for the computational cycles, and how to align service agreements with school hours. Often, the best choice is "nearby but not on-site": public cloud zones governed by domestic laws, supported by long-term clean energy contracts, and connected to education networks.

Another challenge is hardware concentration. Analysts estimate that NVIDIA still accounts for 80-90% of the AI accelerator market. This concentration increases costs and delivery risks for any country scaling sovereign AI. Europe's response is to build public computing resources and diversify hardware options. The EuroHPC/AI Factories model grants access to non-corporate users, while the EU is investing in domestic chip design—such as a €61.6 million grant to Dutch company AxeleraAI for an inference chip aimed at data centers. While schools may not care about tensor cores, they will notice the impact when hardware shortages delay the launch of national reading tutors. Diversification and public access help mitigate these risks, which is vital for education policy and infrastructure planning.

Korea is addressing both challenges head-on. The government has selected five teams to develop a sovereign foundation model by 2027. They are making large GPU purchases, starting with an initial batch of 13,000 units, and have a multi-party plan that could scale to 260,000 GPUs across public and private AI factories. The public message is about national control, but the practical takeaway for education is procurement design: consolidate demand, negotiate energy contracts that align with school schedules, and reserve computing power for public interest. This is how to keep sovereign AI affordable for schools.

A practical sovereign AI agenda for education

The first step is to view sovereign AI as curriculum infrastructure. Use public models for essential tasks—such as assessment feedback, lesson planning, and language support—and require vendors to operate on platforms that comply with local laws or use certified AI Factories. This ensures data residency, accountability, and cost management. It also sets a guideline: models utilized on public networks must be open-source, or at least open enough for education authorities to validate safety, content filters, and logging. Europe’s direction shows the way, with AI Factories designed to provide researchers and small businesses open access, along with broader digital partnerships the EU is forming with countries like Korea and Singapore to share standards and best practices.

The second step is to create the data that models need to support classrooms. This involves gathering curated, consented, and representative datasets: textbooks under public licenses, anonymized exam papers, bilingual glossaries, local history archives, and speech data for lesser-known dialects. Latin America’s method—federating national collections under a regional model and then fine-tuning for each country—provides a solid template. If you want sovereign AI that can teach in Quechua or Romansh, you cannot simply rent it; you must create it. Attach data grants to teacher involvement, fund annotation, and collaborate with universities to ensure rigorous quality control.

The third step is building trust. Teachers will only use tools they can trust or understand. Ministries should create open evaluation tracks that any vendor or public lab can participate in. Define tasks that mirror classroom needs: provide detailed feedback on essays, identify bias in texts, and draft unit plans aligned with local standards. Publish the results and allow districts to choose from a trusted list. The cost of this approach is minimal compared to the expense of a failed national contract. The benefits include real choice and quicker development cycles. Lastly, it is crucial to plan for energy needs. The IEA's projections indicate that energy demand will rise. Education networks should work with national energy planners to avoid overlapping peak testing and tutoring times with times of grid stress.

We began with a stark figure: 260,000 GPUs for a single country’s sovereign AI initiative. While the exact number is significant, its implications are more important. AI is becoming a fundamental part of our infrastructure, with education set to be one of its main users. Suppose governments want models that teach in local languages, adhere to national curricula, and respect public law. In that case, the solution is not to commit to a single foreign platform. Instead, they should build shared capacity, pool risks, and, where possible, open the system. This work is already underway—from Switzerland’s open Apertus to Europe’s AI Factories, Korea’s national rollout, and Latin America’s regional models. The following steps are the responsibility of education leaders. They should treat sovereign AI as a public resource, fund it, assess its effectiveness in classroom applications, and maintain enough openness to build trust. The stakes are real. They involve the words, ideas, and feedback we present to students every day.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AxeleraAI grant. (2025, March 6). Reuters. Dutch chipmaker AxeleraAI gets €61.6 million EU grant to develop an AI inference chip.

Apertus: a fully open, transparent, multilingual language model. (2025, September 2). ETH Zurich/EPFL/CSCS (press release).

Energy and AI—Executive summary & News release. (2025). International Energy Agency. Projections for data-centre electricity demand through 2030.

EU AI Factories—Policy page. (2025, October 30). European Commission, Shaping Europe’s Digital Future.

EuroHPC JU—Selection of the first seven AI Factories. (2024, December 10). EuroHPC Joint Undertaking.

EuroHPC JU—Selects six additional AI Factories. (2025, October 10). EuroHPC Joint Undertaking.

EU–Republic of Korea Digital Partnership Council. (2025, November 27–28). European Commission press corner / Digital Strategy news.

Latam-GPT and the search for AI sovereignty. (2025, November 25). Brookings Institution.

Mistral unveils new models in race to gain edge in “open” AI. (2025, December 3). Financial Times.

NVIDIA, the South Korean government, and industrial giants are building an AI infrastructure and ecosystem. (2025, October 31). NVIDIA (press release).

South Korea accepts the first batch of NVIDIA GPUs under the large-scale AI infrastructure plan. (2025, December 1). The Korea Times.

Comment