AI Grief Companion: Why a Digital Twin of the Dead Can Be Ethical and Useful

Published

Modified

AI grief companions—digital twins—can ethically support mourning when clearly labeled and consent-based Recent evidence shows chatbots modestly reduce distress and can augment scarce grief care Regulate with strong disclosure, consent, and safety standards instead of bans

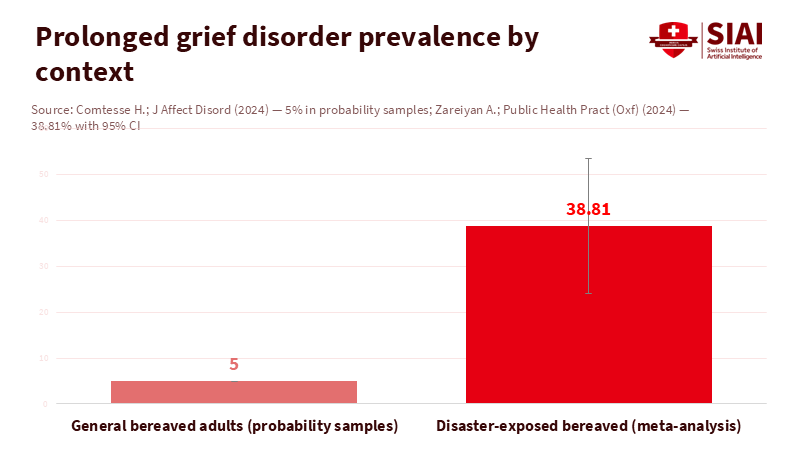

In 2024, an estimated 62 million people died worldwide. Each death leaves a gap that data rarely captures. Research during the pandemic found that one death can affect about nine close relatives in the United States. Even if that multiplier varies, the human impact is significant. Now consider a sobering fact from recent reviews: around 5% of bereaved adults meet the criteria for prolonged grief disorder, a condition that can last for years. These numbers reveal a harsh reality. Even well-funded health systems cannot meet the need for timely, effective grief care. In this context, an AI grief companion—a clearly labeled, opt-in tool that helps people remember, share stories, and manage emotions—should not be dismissed as inappropriate. It should be tested, regulated, and, where it proves effective, used. The moral choice is not to compare it to perfect therapy on demand. It is to compare it to long waits, late-night loneliness, and, too often, a $2 billion-a-year psychic market offering comfort without honesty.

Reframing the question: from “talking to the dead” to a disciplined digital twin

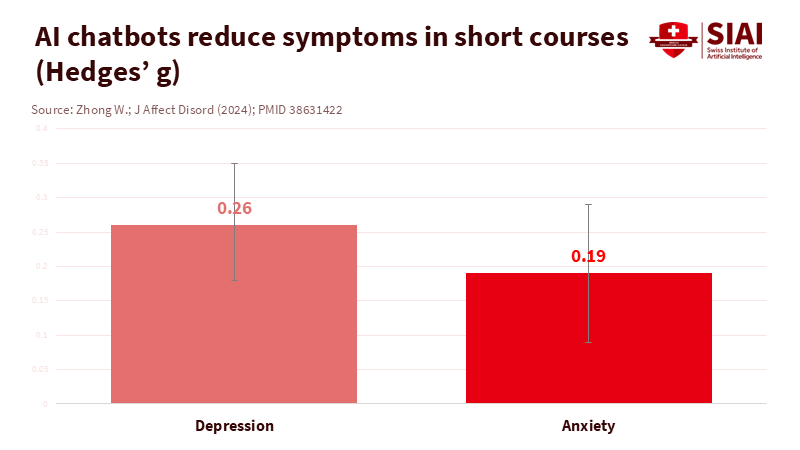

The phrase “talking to the dead” causes concern because it suggests deception. A disciplined AI grief companion should do the opposite. It must clearly disclose its synthetic nature, use only agreed-upon data, and serve as a structured aid for memory and meaning-making. This aligns with the concept of a digital twin: a virtual model connected to real-world facts for decision support. Digital twins are used to simulate hearts, factories, and cities because they provide quick insights. In grief, the “model” consists of curated stories, voice samples, photos, and messages, organized to help survivors recall, reflect, and manage emotions—not to pretend that those lost are still here. The value proposition is practical: low-cost, immediate, 24/7 access to a tool that can encourage healthy rituals and connect people with support. This is not just wishful thinking. Meta-analyses since 2023 show that AI chatbots can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression by small to moderate amounts, and grief-focused digital programs can be helpful, especially when they encourage healthy exposure to reminders of loss. Some startups already provide memorial chat or conversational archives. Their existence is not proof of safety, but it highlights feasibility and demand.

The scale issue shows why reframing is essential now. The World Health Organization reports a global average of roughly 13 mental-health workers for every 100,000 people, with significant gaps in low- and middle-income countries. In Europe, treatment gaps for common disorders remain wide. Meanwhile, an industry focused on psychic and spiritual services generates about $2.3 billion annually in the United States alone. Suppose we could replace even a fraction of that spending with a transparent AI grief companion held to clinical safety standards and disclosure rules. In that case, the ethical response is not to ban the practice but to regulate and evaluate it.

What the evidence already allows—and what it does not

We should be cautious about our claims. There are currently no large randomized trials of AI grief companions based on a loved one’s data. However, related evidence is relevant. Systematic reviews from 2023 to 2025 show that conversational agents can reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, with effect sizes comparable to many low-intensity treatments. A 2024 meta-analysis found substantial improvements for chatbot-based support among adults with depressive symptoms. The clinical reasoning is straightforward: guided journaling, cognitive reframing, and behavioral activation can be delivered in small, manageable steps at any time. Grief-specific digital therapy has also progressed. Online grief programs can decrease grief, depression, and anxiety, and early trials of virtual reality exposure for grief show longer-term benefits compared to conventional psychoeducation. When combined with statistics about grief, such as meta-analyses placing prolonged grief disorder around 5% among bereaved adults in general samples, we see a cautious but hopeful inference: a well-designed AI grief companion may not cure complicated grief, but it can reduce distress, encourage help-seeking, and assist with memory work—especially between limited therapy sessions.

Two safeguards are crucial. First, there must be a clear disclosure that the system is synthetic. The European Union’s AI Act requires users to be informed when interacting with AI and prohibits manipulative systems and the use of emotion recognition in schools and workplaces. Second, clinical safety is essential. The WHO’s 2024 guidance on large multimodal models emphasizes oversight, documented risk management, and testing for health use. Some tools already operate under health-system standards. For instance, Wysa’s components have UK clinical-safety certifications and are being assessed by NICE for digital referral tools. These are not griefbots, but they illustrate what “safety first” looks like in practice.

The ethical concerns most people have are manageable

Three ethical worries dominate public discussions. The first is deception—that people may be fooled into thinking the deceased is “alive.” This can be addressed with mandatory labeling, clear cues, and language that avoids first-person claims about the present. The second concern is consent—who owns the deceased's data? The legal landscape is unclear. The GDPR does not protect the personal data of deceased individuals, leaving regulations to individual states. France, for example, has implemented post-mortem data regulations, but there are inconsistencies. The policy solution is straightforward but challenging to execute: no AI grief companion should be created without explicit consent from the data donor before death, or, if that is not possible, with a documented legal basis using the least invasive data, and allowing next of kin a veto right. The third concern is the exploitation of vulnerability. Italy’s data protection authority previously banned and fined a popular companion chatbot over risks to minors and unclear legal foundations, highlighting that regulators can act swiftly when necessary. These examples, along with recent voice likeness controversies involving major AI systems, demonstrate that consent and disclosure cannot be added later; they must be integrated from the start.

Design choices can minimize ethical risks. Time-limited sessions can prevent overuse. An opt-in “memorial mode” can stop late-night drifts into romanticizing or magical thinking. A locked “facts layer” can prevent the system from creating new biographical claims and rely only on verified items approved by the family. There should never be financial nudges within a session. Each interaction should conclude with evidence-based prompts for healthy behaviors: sleep hygiene, social interactions, and, when necessary, crisis resources. Since grief involves family dynamics, a good AI grief companion should also support group rituals—shared story prompts, remembrance dates, and printable summaries for those who prefer physical copies. None of these features is speculative; they are standard elements of solid health app design and align with WHO’s governance advice for generative AI in care settings.

A careful approach to deployment that does more good than harm

If we acknowledge that the alternative is often nothing—or worse, a psychic upsell—what would a careful rollout look like? Begin with a narrow, regulated use case: “memorialized recall and support” for adults in the first year after a loss. The AI grief companion should be opt-in, clearly labeled at every opportunity, and default to text. Voice and video options raise consent and likeness concerns and should require extra verification and, when applicable, proof of the donor’s pre-mortem consent. Training data should be kept to a minimum, sourced from the person’s explicit recordings and messages rather than scraped from the internet, and secured under strict access controls. In the EU, providers should comply with the AI Act’s transparency requirements, publish risk summaries, and disclose their content generation methods. In all regions, they should report on accuracy and safety evaluations, including rates of harmful outputs and incorrect information about the deceased, with documented suppression techniques.

Clinical integration is essential. Large health systems can evaluate AI grief companions as an addition to stepped-care models. For mild grief-related distress, the tool can offer structured journaling, values exercises, and memory prompts. For higher scores on recognized assessments, it should guide users toward evidence-based therapy or group support and provide crisis resources. This is not a distant goal. Health services already use AI-supported intake and referral tools; UK evaluators have placed some in early value assessment tracks while gathering more data. The best deployments will follow this model: real-world evaluations, clear stopping guidelines, and public dashboards.

Critics may argue that any simulation can worsen attachment and delay acceptance. That concern is valid. However, the theory of “continuing bonds” suggests that maintaining healthy connections—through letters, photographs, and recorded stories—can aid in adaptive grieving. Early research into digital and virtual reality grief interventions, when used carefully, indicates advantages for avoidance and meaning-making. The boundary to uphold is clear: no false claims of presence, no fabrications of new life events, and no promises of afterlife communication. The AI grief companion is, at best, a well-organized echo—helpful because it collects, structures, and shares what the person truly said and did. When used mindfully, it can help individuals express what they need and remember what they fear losing.

Anticipate another critique: chatbots are fallible and sometimes make errors or sound insensitive. This is true. That’s why careful design is essential in this area. Hallucination filters should block false dates, diagnoses, and places. A “red flag” vocabulary can guide discussions away from areas where the system lacks information. Session summaries should emphasize uncertainty rather than ignore it. Additionally, the system must never offer clinical advice or medication recommendations. The goal is not to replace therapy. It is to provide a supportive space, gather stories, and guide people toward human connection. Existing evidence from conversational agents in mental health—though not specific to griefbots—supports this modest claim.

There is also a justice aspect. Shortages are most severe where grief is heavy and services are limited. WHO data show stark global disparities in the mental health workforce. Digital tools cannot solve structural inequities, but they can improve access—helping those who feel isolated at 3 AM. For migrants, dispersed families, and communities affected by conflict or disaster, a multilingual AI grief companion could preserve cultural rituals and voices across distances. The ethical risks are real, but so is the moral argument. We should establish regulations that ensure safe access rather than push the practice underground.

The figures that opened this essay will not change soon. Tens of millions mourn each year, and a significant number struggle with daily life. Given this context, a well-regulated AI grief companion is not a gimmick. It is a practical tool that can make someone’s worst year a bit more bearable. The guidelines are clear: disclosure, consent, data minimization, and strict limits on claims. The pathway to implementation is familiar: assess as an adjunct to care, report outcomes, and adapt under attentive regulators using the AI Act’s transparency rules and WHO’s governance guidance. The alternative is not a world free of digital grief support. It is a world where commercial products fill the gap with unclear models, inadequate consent, and suggestive messaging. We can do better. A digital twin based on love and truth—clearly labeled and properly regulated—will never replace a hand to hold. But it can help someone through the night and into the morning. That is a good reason to build it well.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Digital Twin Consortium. (2020). Definition of a digital twin.

Digital Twin Consortium. (n.d.). What is the value of digital twins?

Eisma, M. C., et al. (2025). Prevalence rates of prolonged grief disorder… Frontiers in Psychiatry.

European Parliament. (2024, March 13). Artificial Intelligence Act: MEPs adopt landmark law.

Feng, Y., et al. (2025). Effectiveness of AI-Driven Conversational Agents… Journal of Medical Internet Research.

Guardian. (2024, June 14). Are AI personas of the dead a blessing or a curse?

HereAfter and grieftech overview. (2024). Generative Ghosts: Anticipating Benefits and Risks of AI… arXiv.

IBISWorld. (2025). Psychic Services in the US—Industry size and outlook.

Li, H., et al. (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis of AI-based chatbots for mental health. npj Digital Medicine.

NICE. (2025). Digital front door technologies to gather information for assessments for NHS Talking Therapies—Evidence generation plan.

Our World in Data. (2024). How many people die each year?

Privacy Regulation EU. (n.d.). GDPR Recital 27: Not applicable to data of deceased persons.

Torous, J., et al. (2025). The evolving field of digital mental health: current evidence… Harvard Review of Psychiatry (open-access summary).

WHO. (2024, January 18). AI ethics and governance guidance for large multimodal models.

WHO. (2025, September 2). Over a billion people living with mental health conditions; services require urgent scale-up.

Zhong, W., et al. (2024). Therapeutic effectiveness of AI-based chatbots… Journal of Affective Disorders.

Verdery, A. M., et al. (2020). Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier. PNAS.

Wysa. (n.d.). First AI mental health app to meet NHS DCB 0129 clinical-safety standard.

Comment