Make Spatial Intelligence in Education the Next Platform, Not the Next Fad

Published

Modified

Spatial intelligence in education measurably boosts maths and STEM outcomes Use world models, but prioritize curriculum, tasks, and teacher practice Fund weekly spatial lessons and assess visual reasoning to scale

The most striking education statistic this autumn did not come from a national exam league table. It went from a classroom experiment. In Scotland, a low-cost, 16-lesson course taught children to visualize 3D shapes and map them onto paper. This program boosted maths scores by up to 19% among seven- to nine-year-olds across 80 schools. It also showed measurable improvements in spatial reasoning and computational thinking. That is not a small change; it is a real enhancement in learning abilities that traditional drills rarely achieve. Early university reports indicate that 96% of pupils made progress, and average spatial gains reached around 20%. Plans are in place for system-level rollout to get two in five primary classrooms by 2028. These are controlled pilots, not marketing slogans. They show us something urgent and straightforward: if we want better maths and broader STEM access, spatial intelligence in education is no longer just an enrichment. It is essential for how students learn and how teachers teach. This success story should inspire optimism about the potential of spatial intelligence in education.

Spatial intelligence in education needs a system, not a slogan

The term “spatial intelligence” sounds appealing at conferences, but it has a straightforward meaning in psychology and education. It refers to the ability to visualize and manipulate objects and relationships in space—mentally rotating, folding, cutting, and changing perspectives. Spatial intelligence is one of the most reliable indicators of success in engineering, computing, and design. It is also more adaptable than many think. Research and recent classroom trials show that targeted practice can improve it, and when that happens, mathematics improves too. The mistake schools often make is treating spatial reasoning as a talent that some students have while others do not, or as a niche skill for CAD labs. It is a general learning skill that helps students understand algebraic structure, interpret graphs, and think about rates, areas, and volumes. Ignoring it is like teaching reading without phonemic awareness.

The second mistake is pursuing tools instead of building a comprehensive system. Tablets, VR headsets, and flashy “world generators” may arrive, but alone, they do not change teaching practices. The Scottish pilots succeeded because they used structured spatial tasks that matched the existing maths curriculum, providing teachers with concrete materials, assessments, and lesson plans. Technology-aided visualization, such as seeing block structures or exploring a 3D model, but the real progress came from a coherent sequence, not from gadgets. "Spatial intelligence in education" will only thrive if it becomes a fundamental part of the curriculum, complete with clear learning goals, frequent low-stakes practice, teacher training, and assessments that value visual reasoning as much as number and text skills. Educators should be guided by the need for a comprehensive system, not just tools, in implementing spatial intelligence in education.

From language-first AI to world models: what classrooms actually need

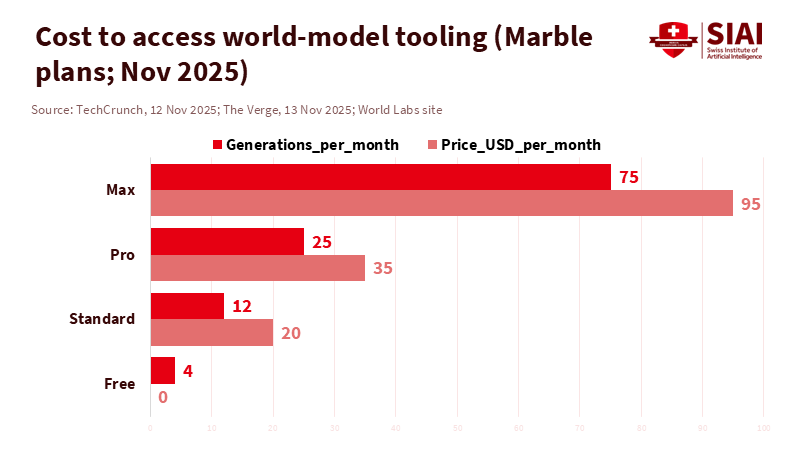

Recent advances in AI make spatial reasoning more applicable in schools. Large language models are not going away; they remain the best tools for drafting, giving feedback, and tutoring. However, the push into “world models” is different. These systems can create and reason about 3D environments and the objects in them. A notable example is Marble, a new platform that transforms text, images, or short videos into persistent, downloadable 3D worlds. It also offers an editor for teachers and students to build a room, a landscape, or a molecule while the AI adds visual details. Pricing starts at free and goes up to paid tiers that include commercial rights and export to Unity or Unreal. This development matters because a classroom can quickly move from a sketch to a navigable scene in minutes, without needing specialized 3D skills. When used effectively, this reallocates time from asset creation to concept exploration.

Still, “street-smart” AI is not just visual. It also involves situational understanding. Good world models allow students to test “what if” scenarios: Does a block tower fall when we change a base? What happens to a light ray in a different medium? How does the flow change with a narrower pipe? The danger lies in thinking that the model feels for us. It does not. It offers a manipulable platform that is effective only if teachers frame tasks that require reasoning and explanation. Schools should clearly understand the limitations: processing costs, content safety, and accessibility. Platforms are advancing quickly—World Labs raised significant funding to develop spatial intelligence—but schools should adopt technology at a pace that aligns with pedagogy, not hype. In education, the critical question is not whether a model can create a beautiful world, but whether students can explain what happens in that world and why.

The evidence base for spatial intelligence in education

What does the research tell us if we step back from the headlines? First, the connection between spatial skills and success in STEM fields is powerful and longstanding. Longitudinal studies and modern replications show that spatial ability is a distinct predictor of who persists and excels in STEM, independent of verbal and quantitative skills. This is why screening for spatial strengths identifies students who might be overlooked by assessments that favor only verbal and numerical abilities. Practically, this becomes a tool for increasing diversity: it opens doors for students, often girls and those from disadvantaged backgrounds, whose strengths shine when tasks are demonstrated instead of just explained.

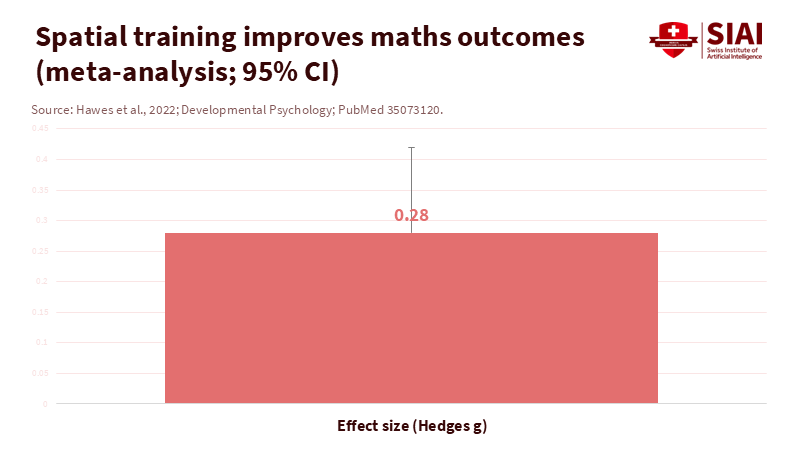

Second, spatial intelligence in education can be developed on a meaningful scale. A 2022 meta-analysis covering 3,765 participants across 29 studies found that spatial training led to an average improvement of 0.28 standard deviations in mathematics outcomes compared to control groups. The benefits were even greater when activities involved physical manipulatives and aligned with the concepts being assessed. This level of improvement, sustained over time, can shift an entire district's progress. Adding work with AR/VR and 3D printing in calculus and engineering in 2024–2025, where controlled studies indicate significant gains in spatial visualization and problem-solving, reinforces this message: when students actively engage with space—whether physical or virtual—their understanding of mathematics deepens.

Third, early national pilots reveal a way to scale this approach. The Scottish initiative did not depend on specialized teachers; it used simple training, standard resources, and repeatable tasks. Participation increased from a few dozen schools in 2023 to hundreds in 2025, involving 17 local authorities, and plans to reach 40% of primary classrooms within three years. Those numbers reflect policy-level commitments, not boutique trials. The gains—double-digit improvements in maths and marked increases in spatial skills—suggest that systems can change rapidly when offerings are straightforward, inexpensive, and integrated into existing curriculum time. This practical and scalable approach should reassure policymakers about the feasibility of implementing spatial intelligence in education.

A policy playbook to make spatial intelligence in education durable

View spatial intelligence in education as a broad capability, not a single subject. In primary years, introduce a weekly spatial lesson that connects to current maths topics—arrays during multiplication, nets while studying area and volume, and scale drawings with ratio. In lower secondary, link spatial tasks to science labs and computing modules that require spatial thinking, such as data visualization or basic robotics. In upper secondary and the first year of university, use world models and affordable VR to make multivariable functions, forces, and molecular structures easier to understand. This model does not require extensive new assessments; it asks exam boards to value diagrammatic reasoning and allow students to show their understanding through it.

Teacher development should be practical and short. Most teachers do not need to master 3D software; they need a set of tasks, examples of student work, and quick videos demonstrating how to conduct a 15-minute spatial warm-up. Procurement should emphasize open export and flexible device options to avoid locking schools into a single vendor. If a district adopts a world-generation tool, insist on privacy protections, local moderation options, and the ability to export to standard formats. Pair any digital tool with non-digital manipulatives. Evidence indicates that tangible materials enhance understanding, particularly for younger students and those who have learned to dislike maths. Equity must be a focus: prioritize spatial modules for schools and student groups underrepresented in STEM, and monitor participation and progress over time.

Finally, be realistic about limits and potential critiques. One critique is that spatial training only offers "near transfer" and will not translate to algebra or proof. The evidence does not support that claim; effect sizes on mathematics are typically positive, and the most substantial gains occur when training aligns with the maths being evaluated. Another critique argues that AI-generated worlds might be considered students. This risk exists if teachers use films. Still, it lessens when worlds become tools for explanation: predicting, manipulating, measuring, and defending their findings. A further critique claims that only wealthy schools can implement spatial technology. The Scottish pilots suggest otherwise: the core elements are practical teaching alongside simple materials, with technology as an aid rather than a barrier. Districts can begin with paper nets, blocks, and sketching before moving to digital environments as budgets permit.

The choice facing schools is not between language-first AI and spatial-first AI. It is between chasing tools and establishing an effective teaching system. Recent compelling evidence comes from classrooms that made spatial intelligence in education an everyday practice rather than an occasional one: weekly tasks, clear objectives, and assessments that value how students visualize just as much as how they solve problems. World models can aid by reducing the time from concept to scene and making unseen structures clear. However, the key to learning remains the student who can examine a world—whether on paper, on a desk, or in a headset—and explain it. The 19% increase in Scottish maths scores is not a limit; it is proof that spatial reasoning is a lever schools can utilize now. If systems invest in training, align the curriculum, and purchase tools that teachers find helpful, this can become a robust agenda for academic improvement. It is time to establish the platform and move past the fad.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Balla, T., Tóth, R., Zichar, M., & Hoffmann, M. (2024). Multimodal approach of improving spatial abilities. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 8(11), 99.

Bellan, R. (2025, November 12). Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs speeds up the world model race with Marble, its first commercial product. TechCrunch.

Field, H. (2025, November 13). World Labs is betting on “world generation” as the next AI frontier. The Verge.

Flø, E. E. (2025). Assessing STEM differentiation needs based on spatial ability. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1545603.

Hawes, Z. C. K., Gilligan-Lee, K. A., & Mix, K. S. (2022). Effects of spatial training on mathematics performance: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 58(1), 112–137.

Medina Herrera, L. M., Juárez Ordóñez, S., & Ruiz-Loza, S. (2024). Enhancing mathematical education with spatial visualization tools. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1229126.

Pawlak-Jakubowska, A., et al. (2023). Evaluation of STEM students’ spatial abilities based on a universal multiple-choice test. Scientific Reports, 13.

PYMNTS. (2025, November 13). World Labs launches Marble as spatial intelligence becomes the new AI focus. PYMNTS.com.

Reuters. (2024, September 13). “AI godmother” Fei-Fei Li raises $230 million to launch AI startup focused on spatial intelligence. Reuters.

The Times. (2025, September 16). Primary pupils to learn spatial reasoning skills to improve maths. The Times (Scotland).

University of Glasgow. (2025, September 17). UofG launches Turner Kirk Centre for Spatial Reasoning. University of Glasgow News.

University of Glasgow—Centre for Spatial Reasoning (Press round-up). (2025, October 1). University of Glasgow.

University of Glasgow—STEM SPACE Project. (2025). STEM Space Project (programme description and outcomes).

Comment