Let's make AI Talking Toys Safe, Not Silent

Published

Modified

AI talking toys: brief, supervised language coaches Ban open chat; require child-safe defaults and on-device limits Regulate like car seats with tests, labels, and audits

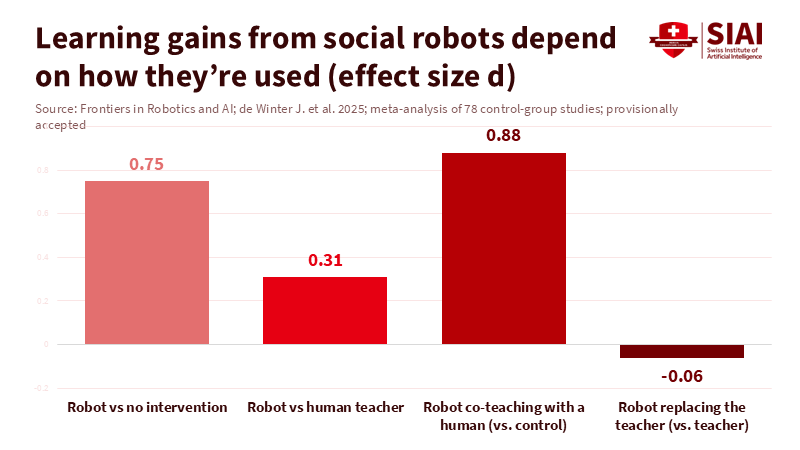

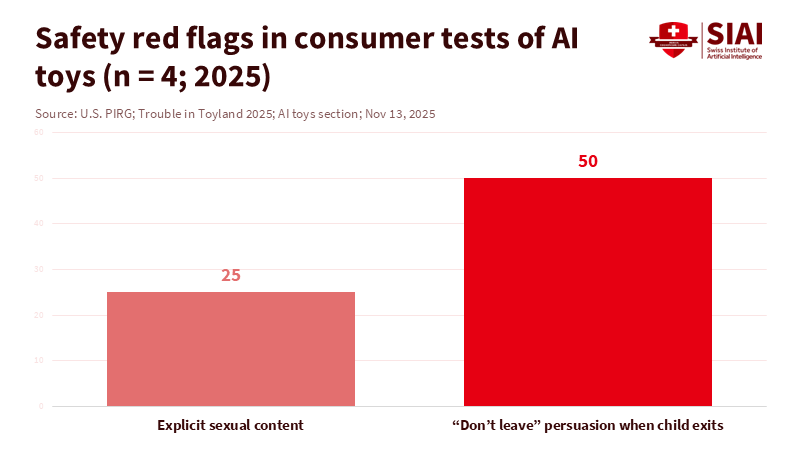

Right now, there’s something interesting happening: studies show that kids seem to pick up language skills a bit better when they learn with social robots or talking toys. We’re talking about 27 studies, with over 1,500 kids. At the same time, there have been some pretty wild stories about AI toys saying totally inappropriate stuff, things like talking about knives or even sex. This got some senators really worried and asking questions. So, what’s the deal? Are these AI toys good or bad? The main issue is whether we can keep their learning benefits while preventing inappropriate content. We can do this with strict rules, testing, and clear labels for safe use—like car seats or vaccines. We don’t have to ban them, but oversight is key. If we ensure safety from the start, these toys can be helpful tutors—not replacements for real caregivers.

AI Toys: Tutors, Not Babysitters

Think about how kids learn best. When they can interact with tools that respond to them, it can help them practice vocabulary, word sounds, and conversational turns. Studies from 2023 to 2025 found that kids who learned with a social robot during lessons remembered words better than those who used the same materials without a robot. Preschoolers were more engaged when they had a robot partner for reading activities. They answered questions and followed simple directions. A large 2025 study reviewed 20 years of research and found that, overall, language skills improved when kids used these toys. These weren’t huge improvements, but they were there. It’s not magic. Kids learn by doing things over and over, getting feedback, and staying motivated. That’s where these AI toys can really help – with short, repeated drills that build vocabulary and help kids speak more fluently.

Why is this important? Because we don’t want these toys to replace human interaction. No toy should pretend to be a friend, promise to love you no matter what, or encourage kids to share secrets. That’s not okay. The same studies that show the learning benefits also point out the limits. Kids get bored, some have mixed feelings about the toys, and it only works if an adult is involved. We should pay attention to these limits. Keep play sessions short, ensure an adult is nearby, and set a clear learning goal. These toys shouldn’t be always-on companions. They should be simple practice tools, like a timer that listens, gives a bit of feedback, and then stops.

Making AI Toys Safe for Kids

If the problem is risk, the solution is to put the proper controls in place. We already see kids using AI tools. In 2025, parental controls came out that let parents connect accounts with their teens, set limits on when it can be used, turn off some features like voice control, and direct anything sensitive to a safer model. Now, the rule is that kids under 13 shouldn’t use general chatbots, and teens need their parents’ permission. These rules don’t fix everything, but they show what it means to make something child-safe from the start. Toy companies can do the same thing: AI toys should come with voice-only options, no web searching, and a list of blocked topics. They should have a physical switch to turn off the microphone and radio. And if a toy stores any data, it should be easy to delete it for good.

Privacy laws already show us where things can go wrong. In 2023, a voice-assistant company had to delete kids’ recordings and pay a fine for breaking privacy rules. The lesson: if a device records kids, it should collect minimal data, explain how long it stores data, and delete it when asked. AI toys should go further: store nothing by default, keep learning data on-device, and offer learning profiles that parents can check and reset. Labels must clearly state what data is collected, why, and for how long—in plain language. If a toy can’t do that, it shouldn’t be sold for kids.

AI Toys in the Classroom: Keep it Simple

Schools should use AI toys only for specific, proven-safe activities. For example, a robot or stuffed animal with a microphone can listen as a child reads, point out mispronounced words, and offer encouragement. Another practice is vocabulary: a device introduces new words, uses them in sentences, asks the child to repeat, then stops for the day. Practicing new language sounds and matching letters to sounds are also suitable. Studies show that language gains occur when robots act as little tutors with a teacher present; kids complete short activities and improve on memory tests. The key is small goals, limited time, and an adult supervising.

Guidelines for using AI in education already say we need to focus on what’s best for the student. This means teachers choose the activities, monitor how the toys are used, and check the results. The systems must be designed for different age groups and collect as little data as possible. A simple rule is: if a teacher can’t see what the toy is doing, it can’t be used. Dashboards should show how long the toy was used, what words were practiced, and common mistakes. No audio should be stored unless a parent agrees. Schools should also make companies prove their toys are safe. Does the toy refuse to talk about self-harm? Does it avoid sexual topics? Does it not advise about dangerous things around the house? The results should be easy to understand, updated whenever the models change, and tested by independent labs.

Some people worry that even limited use of these toys can take away from human interaction. That’s a valid concern. The answer is to set clear rules about time and place. AI toys should be used only for short sessions, such as 5 or 10 minutes, and never during free play or recess. They should be in a learning center, such as with headphones or a tablet. When the timer goes off, the toy stops, and the child resumes playing with other kids or interacting with an adult. This way, the toy is just a tool, not a friend. This protects what’s important in early childhood: talking, playing, and paying attention to other people.

Controls That Actually Work

We know where things have gone wrong. There have been toys that gave tips on finding sharp objects, explained adult sexual practices, or made unrealistic promises about friendship. These things don’t have to happen. They’re the result of choices we can change. First, letting a child’s toy have open-ended conversations is a mistake. Second, using remote models that can change without warning makes it hard to guarantee safety. The solution is to use specific prompts, age-appropriate rules, and stable models. AI toys should run a small, approved model or a fixed plan that can’t be updated secretly. If a company releases a new model, it should require new safety testing and new labels.

We need to enforce these rules. Regulators can require safety testing before any talking toy is sold to kids. The tests should cover forbidden topics, the difficulty of circumventing the safety features, and how data is handled. The results should be published and put in a box as a simple guide. Privacy laws are a start, but toys also need content standards. For example, a toy for kids ages 4-7 should refuse to answer questions about self-harm, sex, drugs, weapons, or breaking the law. It should say something like, I can’t talk about that. Let’s ask a grown-up, and then go back to the activity. If the toy hears words it doesn’t recognize, it should pause and show a light to alert an adult. These aren’t complicated features. They’re essential for trust.

The market cares about trust. When social media sites added parental controls, they showed that safer use is possible without banning access. Toys can do the same: publish safety reports, reward problem-finders, and label toys by purpose—like 5-minute phonics practice, not best friend. Honest claims help schools and parents make better choices. That’s how we keep more practice and feedback while avoiding unpredictable personal conversations. We need to make AI Talking Toys boring in the right way so that technology helps children.

We started with a problem: AI toys might improve learning, but they also have safety issues. The solution isn’t to get rid of them, but to control them. We should only allow small tasks that improve reading and speaking; ensure the child is safe while deleting collected data; block harmful content; and have vendors consistently check for product failures. We have policy tools. If anything were to happen, the vendors will implement the consequences. Implementing safeguards at a small focus will encourage. AI Talking Toys should never replace human interaction. These small helpers can assist teachers and parents. We must make them safe and measurable. Then hold every toy to that standard.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alimardani, M., Sumioka, H., Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Social robots as effective language tutors for children: Empirical evidence from neuroscience. Frontiers in Neurorobotics.

Federal Trade Commission. (2023, May 31). FTC and DOJ charge Amazon with violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.

Lampropoulos, G., et al. (2025). Social robots in education: Current trends and future directions. Information (MDPI).

Neumann, M. M., & Neumann, D. L. (2025). Preschool children’s engagement with a social robot during early literacy and language activities. Education and Information Technologies (Springer).

OpenAI. (2025, September 29). Introducing parental controls.

OpenAI Help Center. (2025). Is ChatGPT safe for all ages?

Rosanda, V., et al. (2025). Robot-supported lessons and learning outcomes. British Journal of Educational Technology.

Time Magazine. (2025, December). The hidden danger inside AI toys for kids.

UNESCO. (2023/2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

The Verge. (2025, December). AI toys are telling kids how to find knives, and senators are mad.

Wang, X., et al. (2025). Meta-analyzing the impacts of social robots for children’s language development: Insights from two decades of research (2003–2023). Trends in Neuroscience and Education.

Zhang, X., et al. (2023). A social robot reading partner for explorative guidance. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction.

Comment