Beyond the 40 Jobs at Risk: AI Job Market Data Educators Can Actually Use

Published

Modified

AI risk lists miss real hiring patterns Job data shows specific roles shrinking and new AI roles growing Education and policy must follow real vacancy data, not myths

Every week, new headlines warn that artificial intelligence could disrupt our careers. One Microsoft-backed analysis of workplace chats indicates that for specific roles, up to 90% of daily tasks could potentially be performed by AI tools, with interpreters, historians, and writers at the highest risk. However, AI job market data presents a different picture. Analyzing 180 million recent job postings, overall demand decreased by a modest 8% year over year, while postings for machine learning engineers increased by 40% following a 78% rise the previous year. Meanwhile, fewer than 1% of advertised roles explicitly require generative AI skills, despite those skills offering higher pay and appearing more frequently on resumes. For educators and policymakers, the clear message is that AI job market data already reveals where work is changing, and it often does not align neatly with the commonly circulated "40 jobs at risk" lists.

AI Job Market Data vs. Headline Risk Lists

The risk lists currently circulating are based on clever but abstract models. The Microsoft study that supports one "40 jobs most at risk" article examined how well AI could perform tasks in different occupations. It produced scores that placed translators, writers, data scientists, and customer service representatives at the top, with some roles deemed 90% automatable. In contrast, manual or relational jobs such as roofing, cleaning, and nursing support rank much lower, exposing only a small portion of tasks. A separate economic study, using two centuries of patent and job data, reaches a similar conclusion: unlike past automation waves that primarily affected low-paid, low-education jobs, AI is expected to affect more well-paid, degree-intensive, often female-dominated fields.

These models are significant as they help identify which types of thinking and communication overlap most with AI's current strengths in pattern recognition, text generation, and number analysis. They also reveal a crucial structural risk: AI may increase pressure on knowledge workers rather than on routine manual staff, reversing the usual trend of technological disruption. However, these models are fundamentally thought experiments. They treat each occupation as an average set of tasks, assume rapid adoption of tools, and do not fully account for budgets, regulations, and managerial decisions that shape hiring in real companies. They indicate where automation could occur, while AI job market data, derived from tens or hundreds of millions of postings, illustrates where employers are actually focusing their efforts today.

What AI Job Market Data Reveals About Real Demand

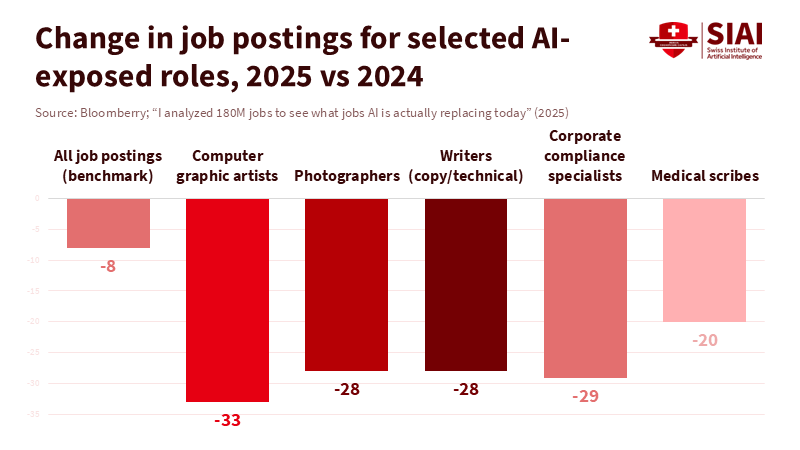

The 8% decrease in job postings identified in a recent analysis of 180 million global vacancies establishes the context: labor demand is cooling, but not collapsing. Within this context, specific roles at risk of being replaced by AI stand out. Postings for computer graphic artists dropped by 33% in 2025, while those for photographers and writers fell by 28%, following similar declines the year prior. Jobs for journalists and reporters decreased by 22%, and public relations specialists saw a 21% decline. These are not vague categories; they represent the execution end of creative work, where tasks often involve producing large volumes of images or text based on a brief. The data indicates that when AI reduces the cost of that output, employers require fewer entry-level workers, even as they continue to hire designers and product teams engaged in research, client interaction, and strategic decisions.

The same dataset reveals a second, less expected cluster of losses in regulatory and sustainability roles. Postings for corporate compliance specialists fell by around 29%, while sustainability specialists saw a 28% decline, closely followed by environmental technicians. The drop occurs across all job grades. Sustainability managers and directors decreased by more than 30%, and chief compliance officer roles fell by over a third. Here, AI is not the main factor. Instead, political backlash against environmental, social, and governance rules, along with changing enforcement priorities, appears to be influencing this pullback. The lesson is uncomfortable yet crucial: some of the most significant job losses in the current AI era arise not from automation but from policy decisions that make entire areas of expertise optional. No exposure index based solely on technical abilities can reflect that reality.

Healthcare provides a clearer view of AI automation in practice. Jobs for medical scribes, who listen to clinical encounters and create structured notes, have dropped by 20%, even as similar healthcare administrative roles remain relatively stable. Medical coders show no significant change, while medical assistants are slightly below the broader market. This trend aligns with the use of AI-powered documentation tools in consultation rooms to transcribe doctor-patient conversations and generate clinical notes almost instantly. Nevertheless, even in this case, the data indicate a limited scope of substitution rather than a widespread wave of job losses. A specific documentation task has become more cost-effective, while the broader team supporting patients remains intact.

On the demand side, AI job market data presents a contrary trend to the alarming headlines. Postings for machine learning engineers surged by 40% in 2025 after a 78% increase in 2024, making it the fastest-growing job title in the 180-million-job dataset. Robotics engineers, research scientists, and data center engineers also experienced growth in the high single digits. Senior leadership jobs decreased only 1.7% compared to the 8% market baseline, while middle management roles fell 5.7% and individual contributor jobs declined 9%. In marketing, most roles mirrored the overall market. Still, postings for influencer marketing specialists increased by 18.3%, on top of a 10% rise the previous year, signaling significant demand for trusted human figures in a landscape filled with AI-generated content.

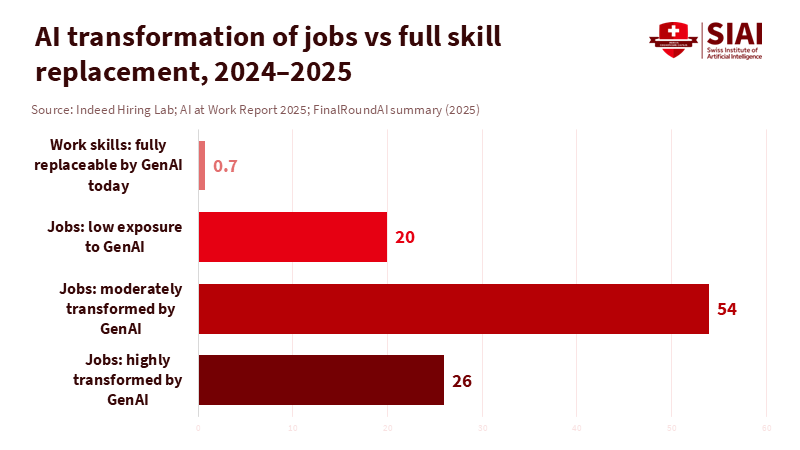

New research from Indeed, summarized in an AI skill transformation index, further supports this view. By examining nearly 3,000 work skills in job postings from May 2024 to April 2025, the team estimates that 26% of jobs will undergo significant changes due to AI, 54% will see moderate changes, and 20% will have low exposure to AI. Yet only 0.7% of skills are considered fully replaceable today. Software development, data and analytics, accounting, marketing, and administrative assistance rank among the most affected groups, with two-thirds to four-fifths of their tasks potentially being supported by AI. Still, job postings in many of these categories remain stable or evolve, indicating that employers are redesigning roles instead of eliminating them. When AI job market data and exposure models are analyzed together, the consistent message leans more toward "significant task reshuffling" rather than "mass unemployment."

Using AI Job Market Data to Redesign Education and Policy

For educators, the main risk is not that AI will render entire degrees obsolete overnight. The real danger lies in curricula continuing to follow outdated job titles while the underlying tasks evolve. AI job market data already illustrates that within the same broad field, some roles are declining while others are expanding. In creative industries, execution roles centered on producing content to a brief face pressure. At the same time, strategy, research, and client-facing design work tend to be more robust. In data and software, routine coding and reporting tasks are increasingly performed by tools, while higher-level architecture, problem framing, and governance gain value. Educators who still define careers solely as "graphic designer" or "software developer" risk steering students toward aspects of those jobs that are already being automated.

A more practical approach begins with the signals of skills in job postings. Although ads explicitly seeking generative AI skills remain a small portion of the total, demand for AI-related skills has surged. A study of job vacancies in the UK finds that jobs requiring AI skills pay about 23% more than similar positions without those skills. LinkedIn also reports a 65% year-on-year increase in members listing AI skills. Furthermore, global surveys indicate that AI competence is now a key expectation for nearly half of the positions employers are hiring for. For universities, colleges, and online providers, this implies two responsibilities. First, they must incorporate practical AI literacy—how to use tools to draft, analyze, and prototype—into most degree programs, not just those in computer science. Second, they need to teach students how to interpret AI job market data on their own, helping them parse postings, understand which skills are bundled, and identify where tasks are shifting within their chosen fields.

Administrators and quality assurance teams can also leverage AI job market data to rethink how programs are evaluated. Instead of primarily relying on long-term employment statistics linked to broad occupational codes, they can monitor live vacancy data in collaboration with job platforms and labor market analytics firms. When postings for execution-focused creative roles decline significantly over two years, while postings for creative directors and product designers remain stable, this should prompt a review of how design courses allocate time between production software and client-facing research or strategy. When machine learning engineers, data center engineers, and robotics specialists all experience substantial growth, technical programs should adjust prerequisites, lab time, and final projects to enable students to practice directing and debugging AI systems rather than just manual coding.

For policymakers, the contrast between theoretical exposure lists and AI job market data serves as a caution against broad, one-size-fits-all narratives. Suppose regulatory and sustainability roles are declining due to political decisions instead of technical obsolescence. In that case, workers in those fields require a different support package than those in areas where AI is clearly reducing demand for specific tasks. Career-change grants, regional transition funds, and public-sector hiring guidelines should align with real vacancy trends rather than abstract rankings of which jobs are "exposed" to AI. At the same time, growth in high-skill AI infrastructure roles suggests that investments in advanced training must complement industrial policy regarding data centers, cloud infrastructure, and robotics so local education systems can fill the jobs created by capital spending.

The education system also plays a key role in helping new workers interpret the confusing landscape of alarming forecasts and optimistic stories. Students now encounter lists of "40 jobs at risk," projections that a quarter of jobs will be "highly transformed," and examples of medical scribes or junior copywriters losing work to AI tools. Without proper direction, the instinctive response can lead to paralysis. Programs that present AI job market data to learners—showing which roles in their fields are shrinking, which are growing, and which skills command higher pay—can help ground those fears in reality. They can also highlight a recurring pattern in the data: the jobs that withstand these changes are those where humans provide direction, exercise judgment, build trust, and interpret outputs that AI alone cannot safely manage.

In this context, the most helpful question for educators and policymakers is no longer "Which 40 jobs are most at risk?" but rather "Which human-centered tasks does AI increase in value, and how do we train for those?" The current wave of AI job market data provides early answers. It indicates declining demand for repetitive execution, uncertain and politically influenced signals in specific regulatory areas, and significant growth in roles related to design, governance, and infrastructure for building and supervising AI systems. It shows that many jobs will be redefined rather than eliminated, and that skills in directing, critiquing, and contextualizing AI outputs are already commanding higher wages. If institutions treat this evidence as a living syllabus—reviewed each year, openly discussed, and translated into course design—they can move past hypothetical lists and support learners in navigating the jobs AI is actively reshaping today, rather than those it might replace in the future.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bloomberry / Chiu, H. W. (2025, November 14). I analyzed 180M jobs to see what jobs AI is actually replacing today. Bloomberry.

Brookings Institution / Eberly, J. C., Kinder, M., Papanikolaou, D., Schmidt, L. D. W., & Steinsson, J. (2025, November 20). What jobs will be most affected by AI? Brookings.

FinalRoundAI / Saini, K. (2025, September 23). 30 Jobs Most Impacted by AI in 2025, According to Indeed Research. FinalRoundAI.

Indeed Hiring Lab / Recruit Holdings. (2023, December 15). Webinar: Indeed Hiring Lab – Labor Market Insights [Transcript].

Sky News. (2025). The 40 jobs "most at risk" from AI – and 40 it can't touch. Sky News Money.

Tech23 / Dave. (2025, October 13). The 40 Jobs Most at Risk from AI…and What That Means for the Rest of Us. Tech23 Recruitment Blog.

Comment