Europe faces a choice: ensuring security without hindering economic progress

Input

Modified

Strengthen defence while protecting R&D and skills to keep growth alive Spend smarter: joint procurement, open standards, and dual-use innovation Fund what proves results—capability gains, cost declines, and real diffusion

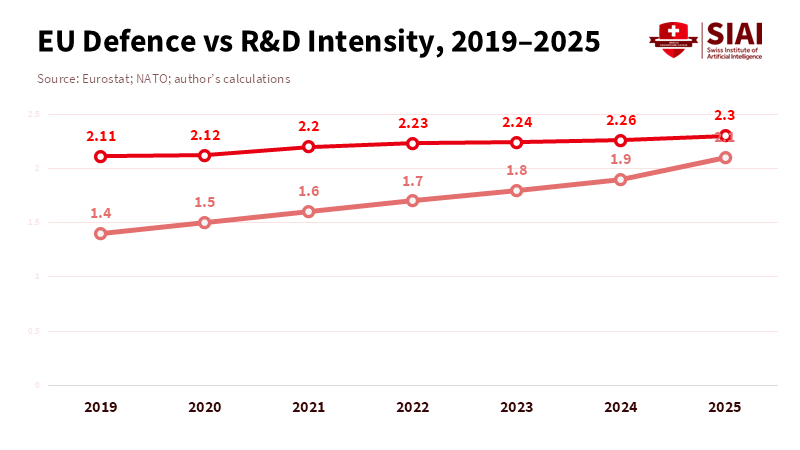

The example of Ukraine, where defense spending consumes roughly 30% of GDP, illustrates how quickly security needs can overwhelm other crucial sectors such as education, research, infrastructure and social care. Although the EU is distinct from Ukraine, it faces similar pressures. Defense expenditures in the EU rose to around 1.9% of GDP in 2024 and are projected to exceed 2% in 2025, with Germany leading in total spending. Some suggest that a credible defense might require well over 3% of GDP. Therefore, the EU requires changes to defense spending that safeguard security while sustaining growth. The danger is clear: if fiscal policies favor procurement but limit research and development, Europe will spend more but gain less actual capability, and slower economic growth will become locked in. This can be avoided by changing budgetary priorities and how security is acquired, developed, and staffed.

Reframing the Trade-Off: Integrating Innovation with Defense

Defense spending is often viewed as distinct from innovation, but this is inaccurate. The allocation of resources is what truly matters. The EU's current fiscal approach gives preferential treatment to defense expenditures while placing stricter limits on other public spending, resulting in a shift of limited resources toward procurement rather than research and development. This is not logical from an economic standpoint. Modern defense capabilities rely on software, automation, data, and advanced computing, which are areas often regarded as discretionary in governmental budgets. If Europe invests largely in military hardware while limiting research and talent development, it will only achieve a short-term boost in equipment, leading to high future maintenance costs and a lack of economic growth necessary to cover these expenses.

South Korea offers a more effective model. Its economic progress was not founded on excessive defense spending; defense expenditures have remained relatively low. Instead, South Korea focused on sustained and intensive research and development, with investments near 5% of GDP in recent years, combined with the quick application of new technologies across its industries. This strategy fostered resilience despite ongoing security threats. Europe should learn from South Korea's growth strategy: dedicating resources to research and development while making wise choices in defense spending.

The Core Fiscal Problem

The main issue is financial. Many EU member states entered the 2020s with high levels of debt and deficits. Rising costs for pensions and healthcare due to aging populations, plus the capital needed for climate and energy transitions, further intensify these pressures. As a result, some governments initially reduce public investment and research. Yet, these are the very factors that support long-term economic expansion and debt management. This is the conundrum facing Europe: how to achieve security without economic stagnation. Current discussions on EU defense spending revisions should begin by distinguishing between expenditures that enhance production and those that do not. While procurement is important, it contributes little to increasing productivity trends. Research and development, technical application, and workforce training, on the other hand, are effective. Regulations should reflect the difference.

The figures are clear: EU defense spending has increased for ten years straight, reaching around €343–381 billion by 2025, about 1.9% of GDP in 2024, and an estimated 2.1% in 2025. Concurrently, total EU research and development spending was about €403 billion in 2024, roughly 2.24% of GDP. Europe requires both, but current fiscal rules favor defense while limiting broader innovation, creating a bias against growth. If the EU needs to spend more on security, it can only be achieved by linking it with greater innovation, as reflected in its regulatory frameworks.

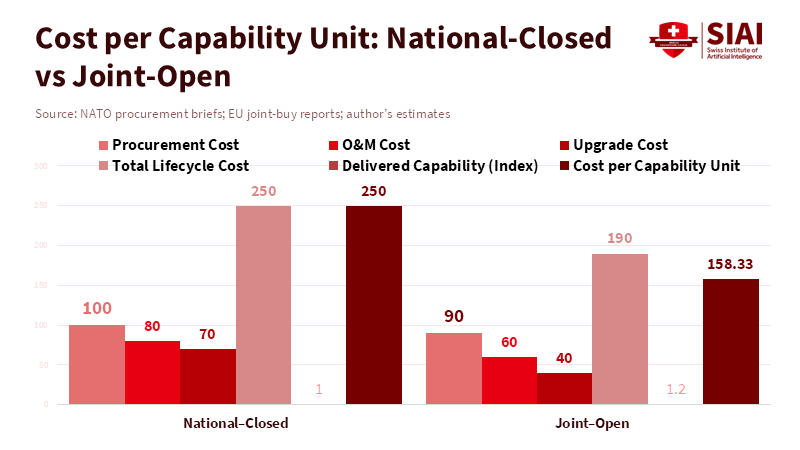

Focus on Better Spending, Not Just More

While quantity is significant, quality is more so. Germany has become the EU’s most significant defense spender and many members aim for higher spending targets. Some suggest that a credible defense may need more than the standard 2% of GDP, and could reach around 3% if not appropriately managed. However, this is not unavoidable. Europe can lower costs by utilizing economies of scale. Joint procurement can reduce redundancy, stabilize demand, and speed up industrial learning. Open architecture and interoperable standards can decrease expenses. Most importantly, directing a portion of procurement toward dual-use research and development—such as for sensors, automation, and secure communications—can convert defense investments into productivity gains across the whole economy. This is how EU defense spending changes can pay for itself in the long run.

Ukraine provides a valuable example. While its wartime spending does not apply to Europe, its rapid adoption of drones, electronic warfare, and software-defined systems is. These advancements depend less on old equipment and more on continuous innovation. Europe should take note and modify its procurement strategies to favor systems that are easily upgraded. By purchasing fewer custom platforms and more adaptable capabilities, Europe can achieve better capability growth at a reduced cost. This involves protecting innovation resources within the fiscal rules.

A Plan Balancing Capability, Growth, and Fairness

A practical plan includes four parts. First, redefine what qualifies for fiscal flexibility by exempting a portion of EU defense spending that clearly funds innovation, such as basic research, testing facilities, dual-use laboratories, and university-industry collaborations. This exemption should be linked to clear progress and measurable outcomes, not just spending. Second, make joint procurement a standard for categories where scale can foster learning. A large and predictable order book will allow European companies to invest in improvements, reducing expenses and accelerating delivery. Third, provide resources for developing talent through dual-use programs, technical training and rotations between defense companies and public labs. Fourth, implement review clauses so that flexible fiscal treatment does not become permanent.

Some will argue that dedicating funds to innovation will require cuts to welfare, and that increased research and development will slow down rearmament in the short term. However, these concerns are not entirely valid. The actual conflict is between low-return expenditures and high-return investment. Europe can protect essential social programs while reforming programs that do not effectively reduce inequality or increase workforce participation. Regarding timing, software-intensive systems can be deployed faster than heavy platforms.

Implications for Education and Industry

Education policy is central to this plan. Although Europe spends heavily on research and development in universities and companies, its distribution is uneven. Business-funded research in the EU is considerably lower than in countries such as South Korea. By creating defense-related cooperative projects, shared testing facilities, and funding robotics, AI, and communications, universities can gain practical experience, which will lead to faster iteration, better tools, and student pathways into shortage jobs.

Additionally, administrators should anticipate increased demand in technical education. If member states dedicate just a portion of GDP to dual-use talent programs, it would produce thousands of more researchers and technicians annually. By tying support to real-world placements and setting clear requirements, institutions, companies, and universities can work together to educate and employ skilled workers, thereby improving both defense and economic growth.

Addressing Potential Concerns

One worry is that Europe cannot manage both stronger security and innovation while following fiscal rules. However, that idea is incorrect. If Europe invests in innovation, its fiscal position will improve as it leverages its already strong base of high-skilled workers to produce both security and economic well-being. Transparency is also key. By publishing achievements, cost analysis, and results, governments can earn public trust.

Additionally, some will point to other countries, like South Korea, that spend large amounts on defense. However, it is more useful to examine South Korea’s investment in research and development and in the development of skilled workers. Europe should target relentless innovation, export standards, and the rapid use of technology. The goal is a credible defense at a sustainable cost through smart procurement that matches the continent’s financial constraints and strategic needs.

Policy Steps for 2026–2030

By mid-2026, the EU should introduce three regulations. First, reserve a portion of every defense program for dual-use research and development with open standards, the release of which should depend on tested prototypes, workforce placement, and SME participation. Second, joint procurement should be required for areas like air defense and communications with clauses that guarantee those efficiency gains will go back to national treasuries. Third, create a bonus for programs that contribute to civilian savings or export growth. This aligns governments, firms, and universities, all around measurable outcomes.

By 2030, success could be defined as defense spending of around 2.5–3.0% of GDP, with a large share going towards software and dual-use research. EU-level programs can reduce costs through learning, and research and development can climb towards 2.7–3.0% of GDP, still less than South Korea, but improving. If the EU can keep research and development at approximately €400 billion while including defense-driven innovation, it can raise economic output without compromising social programs. The issue is not cutting back, but making wise choices. Europe has many educated workers and complex manufacturing. EU defense spending changes should utilize both.

What this Means for Practitioners

For educators, align courses with open standards used in defense programs, not proprietary systems. For university leaders, negotiate research agreements that will guarantee data access and test time for students. For SMEs, focus on the interfaces and sub-systems where learning is effective; for treasury officials, focus on how to measure per-euro capability and spread to civilian sectors. For parliaments, ask for project assessments. The advantage will be a Europe that learns faster and therefore has a better defense.

What if Europe keeps the old path? In that case, procurement will continue to grow while productivity stalls. It will then become politically difficult to avoid cutting from areas such as education and care. The alternative is to use security to promote innovation and diffusion. Europe has the universities, firms, and workers to achieve this. It needs regulations and agreements that reward learning, not just spending.

The high percentage of GDP that Ukraine spent on defense offers a warning, not a target. Europe must never reach that point in peacetime. The way to avoid it is to spend differently and to prove that spending works. Redefine fiscal flexibility to protect, measure, and scale innovation. Purchase resources, build in the open, and train for diffusion. Keep defense credible by reducing costs with software and learning. Europe should also have an explicit social agreement: that those who need help will be protected, the future will be funded, and waste will not be tolerated. If Europe can choose defense spending changes that promote innovation, it can meet its obligations to society and restart economic growth. Spend less where it does not count. Spend more where it counts and grow faster because of increased learning.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Atlantic Council. “Germany Wants to Double Its Defense Spending. Where Should the Money Go?” August 28, 2025.

CEPR VoxEU. “Macroeconomic Impacts of Defence Spending.” 2025.

CEPR VoxEU. “The EU Fiscal Framework Undermines Innovation and Security.” January 5, 2026.

Council of the European Union. “EU Defence in Numbers.” 2025.

Euronews. “Europe’s Defence Landscape: Which Countries Spend the Most?” December 2, 2025.

Eurostat. “R&D Expenditure—Statistics Explained.” December 4, 2025.

Eurostat. “EU Spending on R&D Exceeded €403 Billion in 2024.” December 4, 2025.

NATO. “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2025).” 2025.

OECD. OECD Reviews of Innovation Policy: Korea 2023. 2023.

Reuters. “Rutte Says NATO Must Spend Smarter on Defence or Face Bill of 3.7% of GDP.” January 13, 2025.

Wall Street Journal. “Ukraine Now Has Europe’s Biggest Military. What Happens to It When the War Ends?” December 31, 2025.

World Bank (SIPRI series). “Military Expenditure (% of GDP) — Korea, Rep.” Accessed January 2026.

Comment