Brexit's Shift: How UK Immigration Policy Rebuilt the Skills Base

Input

Modified

Points-based immigration replaced EU free movement and filled shortages Rapid rule swings now strain universities and care services Use a public skills scorecard and align visas with training

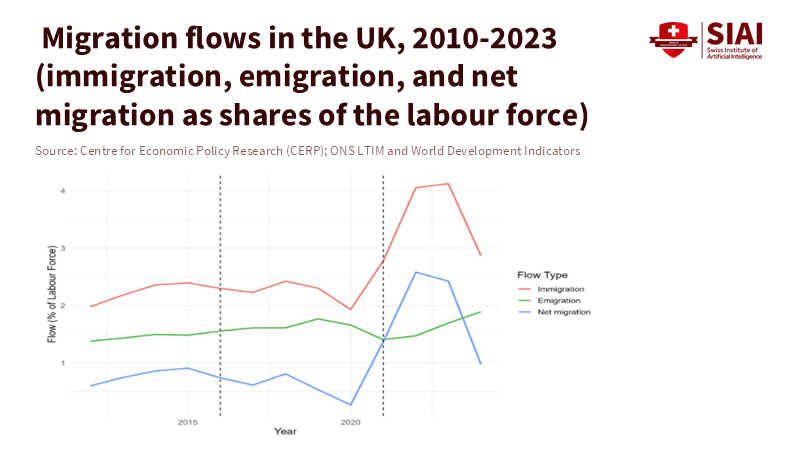

Brexit was supposed to take back control. But net migration to the UK rose to a record 906,000 in the year to June 2023, before falling, and was still higher than before Brexit. That rise was no accident. It came from the UK's points-based immigration system—a system that uses rules to bring in workers from around the world, not just from the EU. This system did what politicians couldn't: it changed where migrants came from, but not how many came. When we look at schools, colleges, and care work, the policy seems more like a way to manage skills than a strict border. This matters for education because a country's workforce must meet its needs. In the UK, this stopped working after Brexit, and the introduction of points-based immigration got it going again.

UK points-based immigration as a post-Brexit change

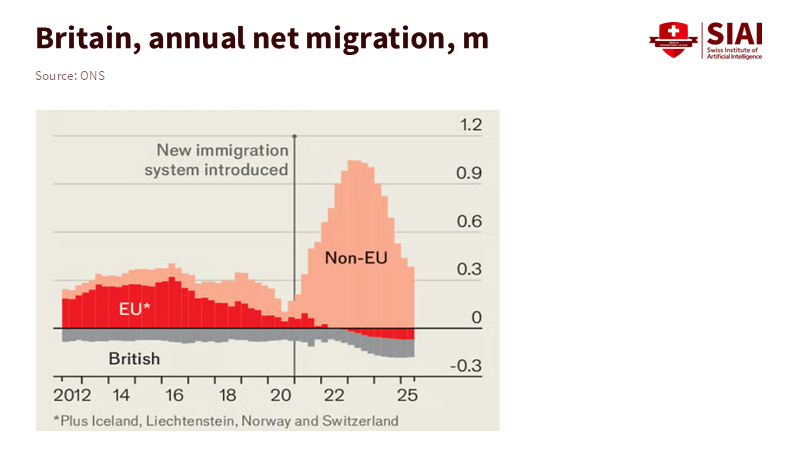

The big rise in net migration after 2021 was mainly from outside the EU. The UK opened up to skilled workers, health and care workers, and students from other countries. From 2021 to 2024, about 3.6 million people came from outside the EU, while fewer came from the EU. This is the key to understanding UK points-based immigration: it shifted the focus to areas where there was a need and where workers could be quickly checked. This created a larger, more focused flow of workers, mainly into health and social care, just when there were more job openings and longer waiting lists. The record net migration in 2023 was from this new system. It was planned to buy time for training and to protect services from the problems that would have come from a total Brexit closure.

The change since late 2024 also matters. Net migration has fallen sharply, to 345,000 in the year ending December 2024, and to about 200,000 in the year to June 2025. This fall is because of new rules: higher salary requirements, stricter family rules, and limits on student dependents. But the key is still the same: the UK still depends on points-based routes where there is a big need. Work permits issued in 2023 were more than three times as many as in 2019. Even with the current limits, the points-based system is still in place. It is now the country’s primary mechanism for managing the labor market. The strange thing is that Brexit reduced EU migration but forced the UK to accept organized, global migration in its place.

Looking Beyond Germany: A Better Comparison

Germany is a tempting comparison. It is big, part of the EU, and stable. Recent work comparing the UK to Germany shows that after Brexit, the UK didn't close; it changed how it brought people in and, for a few years, had higher net inflows than Germany. But the comparison isn't perfect. Germany's population, skills systems, and training model affect how it absorbs workers differently from the UK. A better comparison is by system, not country: free-movement systems (like Germany's) versus points-based systems (like the UK's). When we see the UK as a system change—from free movement to sponsor-based visas—the result is easier to understand. The UK traded easy EU labor for a specific, sector-based inflow. That is why care work and health were the main areas for post-Brexit arrivals.

Comparing systems also makes the timing clearer. UK points-based immigration grew quickly in 2022–2023. Health and Care Worker applications rose sharply after care jobs were added to shortage lists, then fell sharply when rules became stricter. Student routes show the same thing. Dependents were common in 2022–2023, then dropped significantly in 2024 when the rules changed. The system worked as planned: open, then closed. Germany's system is different. Its EU inflows depend on past events and are spread across member states' needs, while its new skilled-immigration changes are still being developed. The UK example shows how a system can quickly react to a labor problem—and how quickly it can change when politicians want smaller numbers. This composition shift is visible in the ONS rate series (Figure 2).

Education and Training: Rebuilding the Skills Agreement

For schools, colleges, and universities, the main thing seen was in the workforce. Health organizations used the UK points-based immigration system to fill long-term gaps in hospitals and social care. This reduced stress on local services that support education, like school nursing and family support. But easy solutions create difficult trade-offs. By 2024 and 2025, the government made rules stricter to reduce numbers and fraud, and visa numbers for care workers and their families fell. The National Audit Office warned that changes had been implemented faster than evaluations, and that the Home Office needed better data to assess their effects. In education, those effects include less stable placements for special-needs assistants, fewer pathways from health colleges into jobs, and a pipeline that starts and stops, making curriculum planning harder. A good skills plan can't depend on emergency migration without clear evidence of financial and service effects.

Universities are at the other end. International enrollment remained high through 2023/24, but policy changes since January 2024 significantly reduced student-dependent visa issuance and began to affect main applicant numbers. For many schools—especially those outside the top universities—non-UK tuition has been what keeps them going. A quick policy change now risks underfunding research, reducing STEM and education master's programs, and shrinking regional training. Early 2025 data show big drops in dependent visas and signs of lower demand. The financial picture is clear: Home Office reports suggest visa limits could cost the government billions over the next five years, with universities losing money through lower tuition and less local spending. If migration must fall, the state needs to support high-skill teaching and regional research.

From Numbers to Outcomes: What to Do Next

The main question for education policy is not whether the UK's points-based immigration “worked.” It did what it was supposed to do: replace EU labor with a global stream focused on shortages. The better question is what we want to achieve—and how education should plan for it. If the goal is stable staffing in care, schools, and STEM jobs, the UK needs a clear path between colleges, apprenticeships, and work visas. That path should show when domestic training increases and when companies can hire from abroad. The current system sends mixed messages: one year of growth, a year of decline, and little evaluation. Education leaders can adapt to change, but not constantly back and forth. The solution is simple: a joint planning schedule, quotas linked to job market forecasts, and a way to track if migration is raising completion rates, care coverage, and graduate jobs where needs are greatest.

That tracking should be public. It should show how many skilled visas support education and training goals, from early-years support to teaching in shortage subjects. It should also show the financial balance. Skilled migrants tend to contribute significantly in their first years, but the distribution of funds matters for schools and local areas. When the government changes the rules, universities and colleges should have time to adjust their offers and housing. And when the government limits student routes, it should fund other growth: scholarships in essential subjects, loan forgiveness for teaching and social care, and apprenticeships that raise completion rates. Migration is not the only thing that matters; it is one tool within a larger plan. The points-based system can stay—and shrink—without stopping the skills engine, if education funding and planning work together.

The Policy Agreement We Need

The next step should be to treat UK points-based immigration as a tool aligned with sector outcomes, not just a number in the news. Start with care and education roles, where shortages hurt achievement most. Track if companies with sponsor licences have stable staffing and better results for students and patients. Publish quarterly data linking visas to service measures—attendance support, special education, clinical placements—as well as to local training. Then set rules that protect students from sudden changes. The big drop in dependent visas may help the net migration target, but it also changes household finances for graduate students and creates new problems for universities that hired in good faith. Stability, not surprise. Instead of measuring success by migration numbers or comparisons to Germany, the real test is whether the UK's points-based system raises completion, expands care, and boosts earnings where educational needs are most significant. The system's value lies in matching skills to need, not in cutting numbers for their own sake. If outcomes improve, keep the approach steady; if not, adjust it. Absolute control comes from focusing immigration policy on building the skills base, not just reducing totals. is real control.

One number shows the choice: Net migration hit 906,000 at its peak and has since fallen by more than half. Those changes came from policy. UK points-based immigration turned a labor problem into a managed flow focused on need, then into a reduction when politicians wanted smaller numbers. For education, the test is whether this system builds the skills we want. That needs clear paths from study to work, funding that supports sudden rule changes, and ways to track staffing and results where shortages are most damaging. We can run a smaller migration system if we plan for it. We can avoid the illusion of control—the cycle that hurts universities and leaves care understaffed—if we use the system carefully. The change is here: not a return to free movement, but a system that matches skills to need and strengthens education.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Economics Observatory. “How Might the UK’s New Approach to Migration Affect the Economy?” 28 October 2025.

Economics Observatory. “How Is the Post-Brexit Immigration System Affecting the UK Economy?” 30 June 2022.

House of Commons Library. Migration Statistics: Concepts and Latest Estimates. Research Briefing SN06077, 1 December 2025.

House of Commons Library. Recent Updates to UK Migration Estimates. Research Briefing CBP-10446, 19 December 2025.

Migration Advisory Committee. Annual Report 2024. 17 December 2024.

Migration Observatory (University of Oxford). “EU Citizens in the UK Labour Market.” 19 June 2025.

Migration Observatory (University of Oxford). “Long-Term International Migration: Flows to and from the UK.” 18 December 2025.

Migration Observatory (University of Oxford). “Student Migration to the UK.” 30 October 2025.

National Audit Office. Immigration: Skilled Worker Visas. 17 March 2025.

OECD. International Migration Outlook 2025. 3 November 2025.

Office for National Statistics (UK). Long-Term International Migration, Provisional: Year Ending June 2024. 28 November 2024.

Office for National Statistics (UK). Long-Term International Migration, Provisional: Year Ending December 2024. 22 May 2025.

Office for National Statistics (UK). Improving Long-Term International Migration Statistics: Updating Our Methods and Estimates. 18 November 2025.

UK Government (Home Office). “Monthly Entry Clearance Visa Applications: November 2025.” 11 December 2025.

UK Government (Home Office). “Tough Government Action on Student Visas Comes into Effect.” 2 January 2024.

UK Government (Home Office). Spring 2025 Immigration Rules Impact Assessment (Skilled Worker and Care Worker). 8 December 2025.

VoxEU/CEPR. Razin, Assaf. “Brexit Migration Shifts: Benchmarking the UK to Germany.” 3 January 2026.

Comment