The Economics of City Size and the New Educational Landscape

Input

Modified

Big cities can be cheaper for global work due to urban economies of scale But congestion and housing costs strain schools first Education must be treated as city infrastructure

Living in major cities often seems expensive. Housing costs are high, commutes are slow, and daily life can feel like a constant wait. Despite this, global companies continue to favor these hubs, drawn by the economic benefits of urban scale. High-density areas allow fixed costs to be spread across a large population. A single airport gate can serve many markets, a concentrated supplier base reduces delays, and a large workforce shortens hiring times. These saved hours translate into cost savings, even when office spaces are expensive. The World Bank reports that nearly 80% of global GDP is produced in cities, which also account for a large share of private-sector job growth.

Education policy is connected to this dynamic, whether or not it is acknowledged. Educational institutions are crucial to a city's basic infrastructure. Because they lower coordination costs, urban economies of scale make hubs appealing to global firms. However, density also brings hidden costs that cities must manage to maintain their advantage. When congestion wastes time, housing prices drive away workers, and public services are strained, educational institutions are among the first to feel the negative impacts. The main argument is straightforward: if a city wants to enjoy the benefits of global networks, it must manage education as a vital part of its infrastructure, not as a separate expense. This shift requires leaders to reassess what they measure, how they allocate funds, and how they plan across the metropolitan area.

The advantages of city size for global business outweigh the lure of cheaper locations

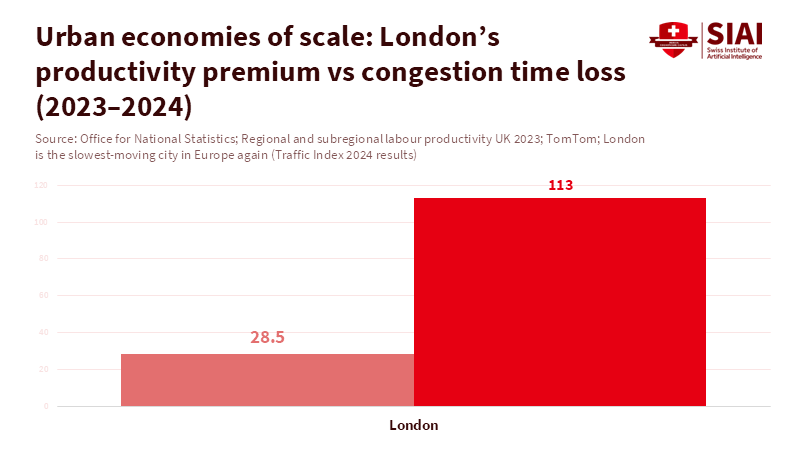

Consistent evidence shows that urban economies of scale increase productivity. OECD studies suggest that doubling a city’s population correlates with a 2–5% rise in productivity. While not a guarantee of success for every large city, this average advantage often stems from quicker connections and faster learning. Data from the UK supports this trend. In 2023, London recorded the highest regional productivity level, with output per hour worked exceeding the UK average by 28.5%. This difference is of value to firms that trade in ideas, contracts, or high-value services. It supports deeper labor markets, more specialized suppliers, and a better chance of swiftly finding the right business connections.

Networks transform this advantage into a daily option. A central hub is where one trip allows for many meetings, which is more critical than inexpensive space when time is limited. In 2024, Heathrow Airport managed about 84 million passengers, a record that shows how face-to-face interaction still underpins deals, research relationships, and supply chains. For a global firm, the cost of missing a key meeting can outweigh a month’s savings on rent. This explains why choosing a cheaper city to save money might work for a short visit, but not for an international operation. The most economical city for global work is often the one with the most dependable connections, the biggest talent pool, and the quickest path to establishing trust.

The economic benefits of urban scale also extend to the education sector itself. A large metropolitan area can operate more specialized programs because demand is consistent. It can support language programs, special education groups, and advanced science and math choices without overextending any single school. Furthermore, it can offer more work-based learning opportunities because many firms are located close to one another, thereby improving the connection between education and employment. Data from Helsinki illustrates how human capital can concentrate in a well-managed hub: in 2024, 53% of residents aged 25–54 had higher education. This concentration can attract more global activity, making education more valuable. However, it also raises the stakes; if access is restricted, the same forces that boost productivity can reinforce inequality.

The drawbacks of urban hubs primarily affect teachers and students

The benefits of urban scale also create difficulties. Traffic, housing costs, and crowded services are the hidden costs of high-density living. As these hidden costs rise, the effects are quickly felt in education. As rent prices increase near the city center, staff members commute from farther away. Students travel across district lines to access specialist support and improved educational opportunities. London shows how quickly time can become scarce. In 2024, TomTom reported an average travel time of 33 minutes and 17 seconds per 10 kilometers in central London. The Guardian reported that delays cost the average driver 101 hours in 2024 and estimated the related economic cost at around £3.85 billion based on the TomTom index. These are not just transport issues. They translate to missed tutoring sessions, late arrivals, less stable staffing, and reduced student energy by the end of the week.

Workforce and management issues make the problem worse. Statistics on England’s school workforce show a sharp rise in teacher vacancies after 2020, which peaked in 2023. Though the numbers decreased in 2024, they stayed high compared to recent years. Research on the teacher job market has shown that salaries and cost of living affect hiring and retention. Big cities are often made up of many local units that are poorly coordinated. OECD evidence links fragmented metropolitan governance to lower productivity. For an area of similar population size, a metro area with twice as many municipalities shows around a 6% lower productivity. Still, a body focused on the entire metro area can lessen the negative impact. When coordination is lacking, schools experience issues like staff shortages and overburdened support services.

These hidden costs extend beyond traffic and are also seen in the job market that schools depend on. When housing prices are driven up by global demand, educational employers must compete with industries that can offer higher pay. This pressure is strongest in subjects with existing shortages and in support roles, where wages are often low. Administrators usually resort to short-term solutions: more substitute teachers, larger class sizes, fewer elective courses, and less enrichment. As a result, students deal with fewer personal relationships and fewer consistent role models in their schools. This is why the idea that “big cities are resilient” is only partially true. Though the infrastructure may absorb challenges, the people can still experience burnout. The economic benefits of urban scale will only remain if cities invest in the everyday systems that keep talent in place, such as affordable access to services, reliable transportation, and reasonable workloads.

Education policy serves as a link between global networks and local communities

If urban economies of scale influence where global work takes place, education policy determines who can participate. The goal is not to replicate the hub model everywhere, but to make hubs sustainable for teachers and students while also making hub networks accessible to those outside the city's core. This begins by seeing education as a metropolitan network: the schools and colleges are the nodes, and transport, digital access, and guidance are the links. When these links break down, the city becomes less accessible than it seems. Without these connections, the hub attracts businesses but excludes too many residents. The solution requires more than just additional money. It also involves clarifying responsibilities across the metropolitan area, sharing data on needs, and developing standard plans for expanding educational resources.

The first practical step is to protect time, since time is valuable in education. In congested hubs, commute time should be seen as a barrier to education, not just a personal problem. Providing dependable school transport, safer routes for older students to walk or bike, and schedules that avoid the worst traffic can increase learning time without changing the curriculum. Teacher time also needs to be valued just as highly. If staff members lose hours to travel and covering classes, the quality of lessons suffers, even in modern buildings. Protecting time can also aid in retention. Teachers who can dependably get home can plan lessons, rest well, and remain in their positions longer. This is a key trade-off in urban economies of scale: cities save firms time, but can waste families' time. Education policy should work to rebalance this.

The second step is to leverage employer concentration to quickly improve skills training and make these improvements available to a broader audience. Hubs can update programs more quickly because they have more companies, more input, and more placement opportunities. A short placement can lead to changes in the curriculum the following term when the business and education partnerships are strong. This is harder to do in areas with fewer employers. Helsinki’s strategy includes a “whole city” approach that connects education, skills, and global appeal. The idea is not to copy Helsinki, but to make a simple cycle: employers signal their needs, educators adjust quickly, and students see a clear career path. After that, people outside the hub can join that cycle without having to move for years through online learning and regional partnerships.

Those who make policy and lead schools must also change how they purchase and share services. A hub can lose some of its advantages when each school or college acts on its own. Purchasing devices and learning platforms together can lower costs and reduce gaps between neighborhoods. Sharing data across the metropolitan area can also reduce discrepancies. If labor demand is growing in one location, training programs should be expanded early, rather than waiting for a crisis. A basic agreement on skills for the metro area can keep these commitments visible and enforceable. For regions outside the hub, the same strategy can fund short training courses and credit transfers, so talent can join hub networks without needing to move permanently. This is a practical approach to give a wider area the advantages of urban scale.

Critics are right about the costs, but wrong about the solution

Some people say that remote work has rendered hubs obsolete, so urban economies of scale will disappear. Evidence does not support this idea. The need for physical interactions is still evident in major transport systems. While remote work changes which tasks require physical closeness, it does not eliminate the value of being together for trust, negotiations, lab experiments, and team learning. Education policy should prepare students for a mix of remote and in-person work, but it should not assume that location is no longer critical. If anything, the standards become higher. When there are fewer in-person meetings, the ones that do occur become more critical. Students need the social and professional skills to use those moments well, which is easier to teach when schools and colleges have strong connections to local businesses and research groups.

Some people argue that hubs are unfair, so the policy should encourage talent to leave big cities. This is a valid worry as housing and traffic can exclude people, and inequality can grow within hubs. Forcing people to leave might increase the nation's costs if global companies still prefer hubs for networking. It is better to share the benefits of the hub by offering credentials that can be used anywhere, strong regional pathways to jobs at hub companies, and short, intensive courses that enable people to join without moving completely. If school budgets depend on national averages, they may not account for the actual cost of staffing and space in a hub, while uncoordinated expenses can waste money. This is where metropolitan governance becomes more than just a planning exercise; it becomes a means to increase productivity. When cities manage education, transport, and housing together, the benefits of urban economies of scale can become real for both companies and families.

The key truth is that big cities can be more cost-effective for meaningful work, even if daily life feels expensive. Urban economies of scale lower the cost of finding partners, sharing ideas, and building trust. Yet these advantages depend on systems that must be managed, most importantly, the education system. When teacher jobs are unstable, and students are exhausted by the city, a hub’s advantages disappear. The solution is straightforward: treat education as essential infrastructure, fund it with the real costs of hubs in mind, and coordinate it at the metro level so that transportation, housing, and school planning all work together. Make the connections between education and work clear, measurable, and accountable, as with other infrastructure projects. Then make the hub’s learning opportunities accessible so people outside the core can connect without relocating.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BST Europe. (2020). Cities’ strategies to cope with the challenges of globalisation: Helsinki. Brussels School of Governance, BST Europe.

City of Helsinki. (2025). 2025–2029 Helsinki City Strategy. City of Helsinki.

Department for Education. (2025). School workforce in England, Reporting year 2024. Department for Education (England).

Heathrow Airport. (2025). UK’s Heathrow profits jump on record passenger numbers (reported results for 2024). Reuters.

National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER). (2024). Teacher labour market in England: Annual report 2024. NFER.

Office for National Statistics. (2025). Regional and subregional labour productivity, UK: 2023. ONS.

OECD. (2014). What makes cities more productive? Evidence on the role of urban governance from five OECD countries (OECD Regional Development Working Papers, 2014/05). OECD Publishing.

The Guardian. (2025). London is Europe’s most congested city, with drivers sitting in traffic an average 101 hours last year. The Guardian.

TomTom. (2024). TomTom Traffic Index 2024: London city center metrics. TomTom.

World Bank. (2024). Urban development overview. World Bank.

Comment