The Intersection of Remote Work and Housework: Implications for Education

Input

Modified

Work from home is changing who does housework Being home is mistaken for being free Education policy must adapt fast

In 2023, data indicated that 35% of employed people in America worked at home, up from 24% in 2019. These individuals averaged 5.1 hours of work at home on those days, suggesting more than just quick email checks. When paid labor happens in the domestic space, remote work and housework become intertwined, presenting new challenges. While family dynamics have not necessarily become more equal, the constant presence at home has become obvious. A laptop on the dining table suggests availability, even during work hours, which can lead to the expectation of household contributions. Data suggests that this shift is not gender-specific, as work-from-home arrangements are common for both women and men. Thus, work and home duties now represent a shared issue for many households.

Work and home responsibilities have become a matter of public concern

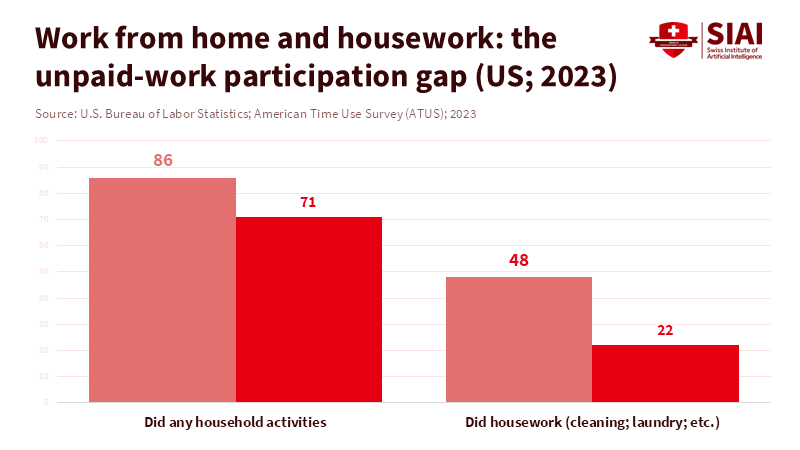

For many years, household work was seen as private. Education systems could treat it as outside their concern. This view was reasonable when work and home were separate. However, remote work has become widespread enough to change established norms. In 2023, 22% of employed people aged 15-64 in the European Union worked from home, either regularly or occasionally. In the United States, records of how time is spent show how this intersects with domestic duties. In 2023, 86% of women and 71% of men did some household tasks on an average day. Women spent 2.7 hours on these jobs, while men spent 2.1 hours. While these differences have decreased, they still matter for who has time to rest, learn, or recover.

A possible risk is that work and home responsibilities quietly become a source of inequality within systems that claim to reward achievement. A 2025 study found that women who worked primarily remotely were less likely to be promoted than those who worked on-site principally. This difference was not seen in men's promotion rates. The point is not that remote work is negative. Instead, flexibility without protections can lead to a visibility tax, where those who are less visible are seen as less driven. Education groups may face the same issue when they assess employees who teach online, create digital courses, or provide student support from home. If the ideal worker is seen as one who is present on campus and can manage home life without problems, then household work can affect career growth.

The real change: Presence is more important than hours

Old rules often connected paid hours to chores, where whoever worked fewer hours did more housework. Remote work is changing this negotiation. Now, presence is as important as hours. Remote work has created a separation between small periods of availability that did not exist when commuting. Gaps between video calls can become time to unload the dishwasher or start dinner. These small tasks add up, and the person at home becomes the default responder. Online discussions show this change, with many people assuming the person at home should handle more, while others argue that paid work at home should still be respected. The conflict shows a new norm: the household now views location as a sign of capacity. This is why debates focus on whether a partner works from home, whether they should do more housework, or whether chores should be divided by paid hours.

Studies suggest that presence can shift norms, but it can also repeat old patterns. A 2024 study using data from Japan found that working from home increased the time men spent on chores and with their families. It also changed attitudes, making people value life more than work. This supports the view that remote work can involve men in domestic routines and weaken the stigma around men doing care and chores. In the UK, evidence suggests that these gains are not guaranteed. A study of home-based work and time use found gender differences in how remote work affects daily schedules and well-being, including in the experience of unpaid work and leisure. When culture expects women to manage the home, flexibility can become extra unpaid work. The same kitchen table that enables remote work can also serve as a spot for domestic tasks.

Education is key to this shift because remote work is common among higher-educated workers, whose families often have demanding schedules. In the U.S., among workers aged 25 and over, 52% of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher did some work at home on workdays, compared with 22% of those with only a high school diploma. So, the families most impacted by work and home norms are also likely to be raising kids in school systems that follow strict schedules. This creates stress, missed deadlines, and reduced participation, especially when schools expect an adult to be available midday for forms, meetings, or calls. Remote work changes the household agreement, and the education schedule often decides who pays the cost.

How Education Systems Can Address the Issue

Education groups already handle the connection between paid work, learning, and family life through start times, after-school programs, meeting hours, and beliefs about who can respond at 2 p.m. A work-from-home setting makes these beliefs clear. For staff, predictable flexibility matters more than vague permission. A policy that says work from home when needed can be a trap if " when needed is read as only when childcare fails, or if employees feel they need to be always reachable. A better model is clear remote days, set hours for meetings, and clear rules about response times. Leaders can also protect remote workers from being penalized for their absence by standardizing assessment, documenting work, and making support intentional rather than informal. These simple fixes can stop household work from slowing down some careers. Meeting times are also important. If meetings are in the mid-afternoon, the system assumes someone else is doing the pickup. Hybrid work only helps if schedules also change.

Student policy needs the same realistic view. Many learners are caregivers. Notes show that about 20% of higher education students are parents, often facing childcare problems. A separate study focused on undergraduates put the number of student-parents at over 3.1 million. About 44% of them were enrolled in fully online programs. Online study can reduce travel time, but it can also increase the clash between work and home. When a student learns at home, the house often gets busier. Groups can offer predictable, flexible exam times and support such as childcare, emergency support, and clear steps for short-duration absences. The goal is not to lower standards, but to stop timing from being a barrier.

Curriculum also matters, and it can be helpful. Career training often sells remote work as total freedom. Students should see the bigger picture. Remote work changes agreements at home, shifts unpaid work, and can hurt careers if employers value face time. This belongs in skills modules, teaching education, counseling, and even first-year orientation for students who work. Programs can teach students how to set limits, write work agreements, and know when flexibility is being traded for unpaid work at home. Teacher training can include family-aware communication. Schools should not always call the same parent at the same time of day, and should not schedule key meetings at times that penalize caregivers. When education treats household time as real time, it supports learning and reduces burnout for staff and families.

Addressing Concerns

Some say norms will fix themselves as couples become more equal. Progress is being made. However, data still shows differences in routine chores. Women were more likely than men to do housework, such as cleaning or laundry (48% versus 22%). The issue is not that every household is unfair. It is that women still carry the daily jobs that are hard to postpone. Remote work can reduce that gap if it involves men in more routine tasks, but it can also widen it if the person at home becomes the problem-solver. Policy should assume mixed results and provide support to reduce downside risk.

Some believe that remote work is ending as companies bring people back to offices. Data does not support this. Work is being done from home for about a quarter of paid workdays among people aged 20–64. In Europe, data shows digital patterns. In 2024, 52.9% of EU companies met online. These measures differ, but the trend is consistent. Remote work is now part of the job market, not a detour. This matters for education planning. The issue will continue to shape attendance, involvement, staff retention, and student support needs.

The data signals a new normal. When a third of workers do some work at home, the issue becomes the pattern that children watch, students live inside, and educators manage. The goal is not to suggest one clear way to divide tasks. The goal is to stop a return to old roles under a new name and to prevent flexibility from turning into overload. Education leaders can align schedules with new work patterns, protect remote staff from penalties, and build student support that treats household time as an absolute limit. This is basic institutional work in a world where work now lives at home. Start by making time visible, protecting remote work from stigma, and measuring results by output. Then, teach students the new rules of the issue before they learn them the hard way.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Council on Education. (n.d.). Student-Parents in the U.S. Higher Education System (infographic). American Council on Education.

Buckman, S. R., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2025). Measuring Work from Home (NBER Working Paper No. 33508). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). American Time Use Survey — 2023 Results (USDL-24-1208). U.S. Department of Labor.

Eurostat. (2024). Employed persons working from home by frequency and sex (EU Labour Force Survey; dataset lfsa_ehomp). Statistical Office of the European Union.

Eurostat. (2025). 53% of EU enterprises held remote meetings in 2024 (Eurostat news release). Statistical Office of the European Union.

Giménez-Nadal, J. I., & Velilla, J. (2024). Home-based work, time allocations, and subjective well-being: Gender differences in the United Kingdom. Journal of Happiness Studies.

Inoue, C. (2024). Working from home leads to more family-oriented men. Review of Economics of the Household.

LeanIn.Org & McKinsey & Company. (2025). Women in the Workplace 2025. LeanIn.Org; McKinsey & Company.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2024). Double Duties: Student-Parents’ Struggle to Find Child Care and How State Policy Can Help. National Conference of State Legislatures.

Comment