When Search Acts as a Tutor: Competition Policy in the AI Age for Public Education

Input

Modified

AI is turning “search” into a default tutor in schools Antitrust helps, but it moves too slowly for education Open standards and portability keep schools from lock-in

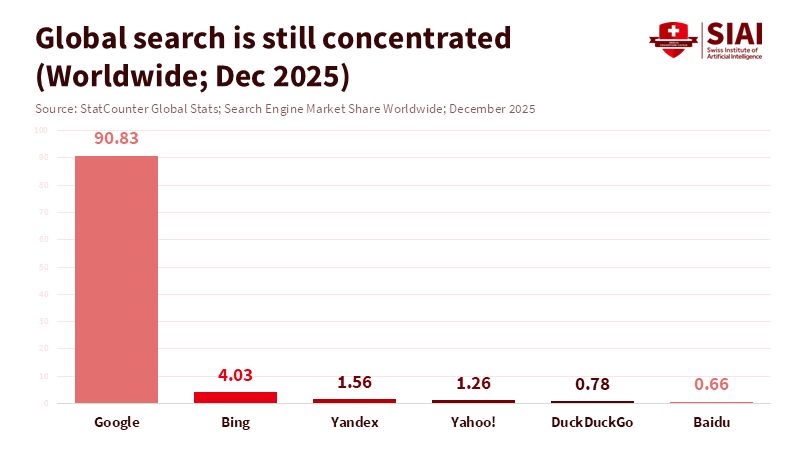

Competition policy in the age of AI is now education policy: It must influence how learning tools are acquired, integrated, and changed—not simply penalize dominant companies. As of December 2025, Google held approximately 90.8% of the global search market, demonstrating its central role in how people find answers. However, the nature of search is changing. By May 2024, ChatGPT saw a peak of 80.7 million daily visits—users are adopting chat as a new internet gateway. Courts are recognizing this shift. In the U.S. search case, the court didn't require the sale of Chrome or Android. Instead, it focused on restrictions and oversight to create opportunities for competitors, observing that AI is reshaping the field. The lesson for schools: ensuring choice remains possible depends on how competition and education policies adapt.

AI-era competition policy involves market structure, not just courtroom action

Antitrust law is designed to proceed cautiously, relying on evidence and due process. AI markets move quickly. A model update can alter behavior in weeks, and a new default setting can quickly shift distribution. Even when a court identifies unlawful behavior, the solution is limited by what the court can oversee. In the Google case, the decision centered on conduct limits, including disclosures and access rules tied to key search data, supported by technical oversight. It rejected actions such as divesting from Chrome or imposing broad choice screens. This outcome isn't inherently “weak” or “strong.” It indicates that courts can reopen avenues, but they don't design what follows.

The timing problem is sharper because generative AI obscures the market boundary. A chatbot can serve as a search engine, study partner, and drafting tool concurrently. The decision acknowledges that emerging GenAI products affect competitive conditions. Still, global search share remained above 90% through December 2025. This situation reveals a difficult truth: Competition can expand marginally while core dominance persists. Default settings, accounts, and integration continue to affect people's initial choices. Reports related to the case also show that default placement can involve payments in the tens of billions. In practice, market power is often about distribution strategies rather than product quality.

Education sees the impact of distribution strategies early. Schools don't simply use apps; they adopt workflows. A learning platform determines where assignments are, how feedback is delivered, and what constitutes acceptable help. An AI assistant included in the same package as accounts, storage, and classroom tools becomes the automatic default tutor. Antitrust action is relevant because exclusionary behavior still matters, but it only offers a partial solution. AI competition policy for education must take a proactive approach. It should make changes possible before reliance solidifies. This means treating procurement, interoperability, and data rights as competitive factors. It also requires acknowledging that public education is governed by markets that change faster than it can adapt, and rules must address this.

The public sector's limited capacity is a key factor in platform power

Public education is vast, but its resources are limited. UNESCO’s Education Finance Watch shows government education spending around the mid-single digits as a percentage of GDP across regions, further strained by an uneven recovery after the pandemic. HolonIQ estimates the global education market at about $7.6 trillion, with governments funding roughly 60–70% of the total. These numbers should suggest influence, but influence requires buyers to compare options, assess claims, and enforce contracts effectively. Many systems lack these abilities. Procurement is slow, IT teams are small, and legal review is overburdened. Platform power in education then results not only from size, but from the difference between private-sector speed and public-sector capacity. The buyer side is also split into thousands of districts and campuses that negotiate independently, preventing shared learning.

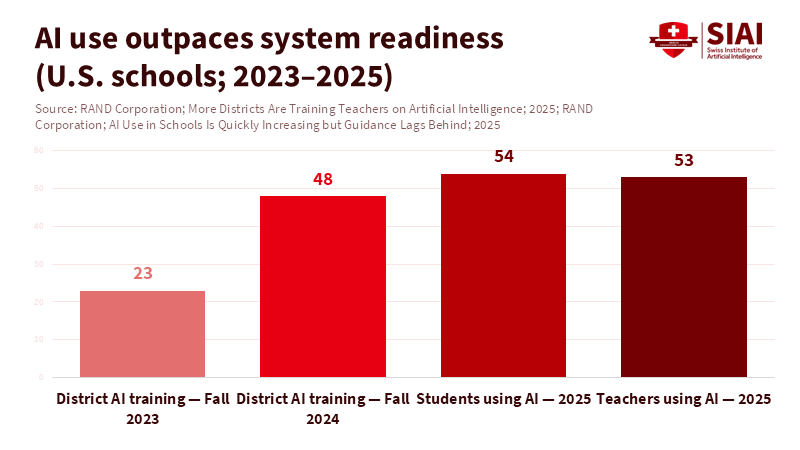

AI adoption is worsening this difference. RAND found that 48% of U.S. districts trained teachers on AI in fall 2024, up 25 points from fall 2023. Another RAND report found that in 2025, 54% of students and 53% of teachers used AI for school. Pew found that 26% of U.S. teens used ChatGPT for schoolwork, up from 13% in 2023. However, use does not ensure preparedness. Pew’s teacher survey found that few believe AI tools are more helpful than harmful, with many uncertain. This indicates a governance issue: Tools are arriving faster than shared guidelines. The importance of these statistics lies in their origin from large surveys, not isolated news stories.

AI competition policy cannot be confined to courtrooms. A court can limit exclusivity and require data sharing, but it cannot create the staff necessary to assess models, audit vendors, and ensure compliance across many schools. The Justice Department presented the Google decision as a means to open a market restricted by distribution tactics, focusing on AI distribution and the advantages of scale. Education faces a similar challenge whenever a tool is the default because it’s bundled, preloaded, or easiest to find. Without sufficient public sector capacity, schools accept convenience, leading to dependence, which is then labeled innovation because leaving is not possible.

Turning AI-era competition policy into accessible options for learning tools

The goal is not to penalize scale, but to stop it from becoming restrictive. Restrictiveness in digital markets typically comes from data immobility, inflexible workflows, and contracts that maintain default settings. The Google decision addresses distribution and access to key elements because these are the levers that make competition possible. Schools can use this logic through procurement. An AI assistant should be replaceable without disrupting assessment processes. Districts should be able to change platforms without losing learning records or accessibility settings. AI competition policy becomes effective when exiting is genuinely possible, not just a last resort. Otherwise, the easiest tool becomes the default choice.

Digital public infrastructure provides a foundation for these possibilities. The World Bank calls for shared digital elements that allow services to work together while maintaining public governance. In education, this suggests standardized identity, consent, and record formats usable by any approved tool, and clear, vendor-neutral interfaces for importing and exporting records, rubrics, and accommodations. OECD work on digital transformation of public procurement highlights that standards, skills, and oversight are essential, not just new software. The policy move involves writing contestability into contracts and systems, allowing new entrants to compete on quality rather than restrictiveness. With mobile data and workflows, small and local providers can compete without requiring schools to start over.

Some will say that portability threatens privacy, open interfaces create security risks, and sharing responsibilities stifles innovation. While real, these risks aren’t reasons to accept restrictiveness. Portability can help preserve privacy through data minimization, role-based access controls, and logging practices. Open interfaces can be safer because they are testable and monitorable. Innovation also depends on contestability. When switching is impossible, the main incentive is to defend the system rather than improve learning. A better approach is layered: strict privacy rules, transparent technical standards, independent audits, and procurement terms allowing schools to combine tools. Privacy-by-design and security testing should be included in procurement, not added after implementation.

What educators and policymakers require before the market shifts further

Educators must view AI tools as part of a market that needs governance, not merely gadgets that need approval. Administrators should consider whether a product increases dependence or supports choice. Contracts for bundled AI assistants should protect the right to use other assistants and retain settings. Training should be tied to product evaluation and classroom rules, ensuring the default isn't just the easiest option to click. When students use AI, the system should track which tool was used, under what policy, and with what data access. This isn’t monitoring; it's basic accountability in a market where tools can influence learning. Clear standards for acceptable use and transparent logs help maintain instructional focus.

Policymakers need to broaden their view beyond single-firm divisions. The European Commission’s 2025 action against Google’s ad practices shows that concerns about market power extend across all aspects of online information. In the U.S., the next steps in the search case involve appeals, and AI's role in arguing solutions. Education policy shouldn’t wait for these issues to be resolved; classrooms are already key channels for AI. The state must make this market safe and competitive through standards, procurement capacity, and data rights, not just lawsuits after harm occurs.

A common concern is that standards slow innovation and lead to inflexibility. The evidence suggests the opposite. Standards can broaden the field by reducing integration costs and enabling schools to test tools without completely changing platforms. Competition then centers on learning value. A good approach includes a small set of interfaces, model contract terms, and funding for shared testing. OECD work emphasizes the importance of shared data in reducing waste and improving outcomes. The same applies to education: Make assessment and exit easier, and new tools can become safer to adopt. Schools can then adapt without risk.

The key statistic is the one we started with: Roughly 90.8% of global search still went through one company at the end of 2025, even as AI use increased. This shows platform-era restrictiveness. In education, it appears as a single login that serves as the classroom, library, tutor, and grader. Antitrust action is helpful when damage is shown, but it cannot replace public support or keep pace with fast-changing interfaces. AI competition policy should be seen as an education policy, requiring open frameworks, portability, and funding for those enforcing regulations so schools select tools based on quality, not restrictiveness. If public systems wait for the next lawsuit, classrooms will continue to inherit choices made by companies. Instead, they should build capacity and possibilities to guide change.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. (2025). Judge orders search shakeup in Google monopoly case, but keeps hands off Chrome and default deals.

HolonIQ. (2025). The Size & Shape of the Global Education Market.

OECD. (2025). Digital transformation of public procurement.

Pew Research Center. (2024). A quarter of U.S. teachers say AI tools do more harm than good in K–12 education.

Pew Research Center. (2025a). About a quarter of U.S. teens have used ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the share in 2023.

RAND Corporation. (2025a). More Districts Are Training Teachers on Artificial Intelligence.

RAND Corporation. (2025b). AI Use in Schools Is Quickly Increasing but Guidance Lags.

Reuters. (2025a). What comes next in Google’s antitrust case over search?

Reuters. (2025b). Google hit with €2.95 billion EU antitrust fine over adtech practices.

Similarweb. (2024). ChatGPT hits daily traffic record as search engine rumors swirl.

StatCounter Global Stats. (2025). Search Engine Market Share Worldwide (December 2025).

The Verge. (2025). Google and Apple’s $20 billion search deal survives.

UNESCO. (2024). Education Finance Watch 2024.

United States Department of Justice. (2025). Department of Justice Wins Significant Remedies Against Google.

United States v. Google LLC, No. 1:20-cv-03010 (D.D.C. Dec. 5, 2025). Memorandum Opinion and Final Judgment materials.

World Bank. (2025). Digital Public Infrastructure and Development: A World Bank Group Approach (Digital Transformation White Paper, Volume 1).

Comment