The Return of the Neutral Rate: How a Higher Normal Impacts Education Finance

Input

Modified

The neutral interest rate is rising Borrowing costs for education will stay higher Hedge risk and fund only projects with fast, proven payback

In 2025, the U.S. implemented a 10% tariff on almost all imports, which caused price changes and strained supply chains. This event put a macroeconomic idea, the neutral interest rate, back in focus. The neutral rate is the real rate at which neither economic activity nor inflation accelerate or slow. For about ten years, the opinion was that it was declining. Then inflation, large deficits, and trade conflicts changed the discussion. Some central bank analysts now estimate a higher normal rate than markets expected last year. The central bank of Japan increased its policy rate to levels not seen in thirty years and considered further increases. The U.S. Federal Reserve lowered rates in 2025, but then became cautious as inflation slowed. If the neutral interest rate has increased, low-cost money will be available for longer than expected by schools, colleges, and investors in education technology. This shift will affect tuition, bond agreements, campus building projects, and the expense of digital changes.

Reasons for a Possible Rise in the Neutral Interest Rate

The neutral interest rate is not directly observable. Economists estimate it based on growth, inflation, and economic slack. While different models give different results, the basic idea is clear. When policy rates are close to the neutral rate, inflation is stable, and the economy is operating near its potential. When policy is below the neutral rate, demand is high. When it is above neutral, demand decreases. The key issue for 2025 is the direction of change. Several factors now suggest a move upward after years of decline. Demographics are changing, public debt is higher, and there is major early investment in energy, chips, and security. Deglobalization and tariffs increase costs and alter relative prices. All of these can raise the neutral rate because there is a greater need for saving to meet investment, and higher risk and policy issues increase required returns.

Evidence continues to build for education finance teams to consider. The Cleveland Fed’s 2025 model places the U.S. nominal neutral rate near 3.7%, with broad ranges still above pre-pandemic levels. The New York Fed also provides estimates above the lows of the 2010s, though with uncertainty. Since 2024, the Bank for International Settlements has warned that major shifts such as AI spending, the green transition, and supply chain duplication may keep real rates higher than markets expected. Tariffs increased import prices and changed the cost structures for educational institutions. If the world’s largest economy applies broad tariffs, the cost landscape shifts for schools as well. A higher neutral interest rate results from rising deficits, increased investment demand, and persistent price shocks. Recent moves and discussions by the Bank of Japan also support the view that global rate norms are shifting upward.

Impact on Education Finance from a Higher Neutral Interest Rate

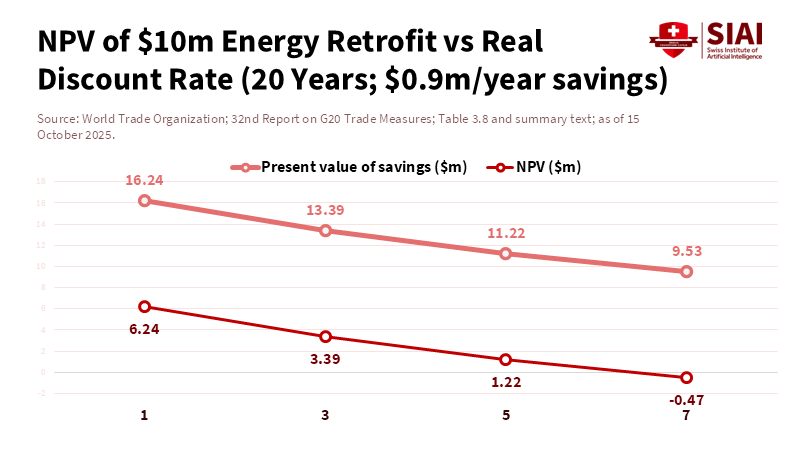

Education depends on inexpensive, long-term capital. School districts sell bonds to rebuild old schools. Universities borrow to upgrade labs and dorms. Education technology companies spend money as they grow. If the neutral interest rate is higher, the minimum borrowing costs will also be higher. Policy rates can sometimes drop, but if the neutral rate has risen, yields will probably increase. This increases the coupon rate on the next bond issue and raises the discount rate in project valuation. A change of 100 basis points in the discount rate may change a net present value calculation from positive to negative. A public district with a $200 million building plan and a 30-year repayment period will incur millions more in interest over the life of the debt. In states with limited school funding, this difference may reduce teacher hiring, maintenance, and student support.

The impact extends beyond coupon rates. Inflation uncertainty causes lenders to require term premiums. Projects requiring significant capital, such as research computing data centers, campus microgrids, and HVAC upgrades, will face higher required rates of return. Rising public debt increases the strain. Recent work from the Congressional Budget Office and Federal Reserve analysts suggests that higher debt increases long-run interest rates by measurable amounts. If federal borrowing remains high, municipal borrowers will pay more, even if their finances are strong. Education systems in Europe face related concerns. Current work from the IMF and ECB places the euro-area neutral real rate around zero, but notes significant uncertainty. If Europe’s neutral rate increases due to defense and energy investments, public universities will experience higher financing costs.

Adjusting Policy to a Higher Neutral Interest Rate

U.S. monetary policy lowered rates three times in 2025 as inflation eased, but decisions were contentious. Meeting notes from late 2025 showed a divided committee and slow progress to 2% inflation. If the neutral rate is higher than many expect, aggressive rate cuts might slow disinflation. Tariffs can push inflation higher by raising import costs and disrupting supply chains. Education leaders should treat the neutral rate as adaptable, watching risks from cutting rates too deeply. This may mean pausing rate cuts sooner, using all available tools, and trusting real rates to do some of the heavy lifting. The important takeaway for education finance: don’t expect a return to the ultra-low interest rates seen in 2015. Review your debt at these new levels and prepare for wider swings in inflation.

The global situation is similar. The Bank of Japan’s move to 0.75% in December, the highest in 30 years, showed a change for a country used to zero rates. Later discussions clarified that more increases were possible. The main implications for other countries are rising global borrowing costs, increased appeal for yen assets, and higher term premiums in the U.S. and Europe. Rebuilding supply chains due to tariffs also sets a floor under global real rates. To address these challenges, central banks should be patient and focus on data. School systems and universities should plan conservatively, with room for unexpected events. If the neutral interest rate is a guidepost, it now points to a higher level than markets expected.

Actions for Education Systems in a Higher Neutral Interest Rate World

First, focus on project quality over perfect timing. When the neutral interest rate increases, the reliable way to create value is via better cash flows and reduced risk. For schools, this means combining energy improvements with contracts that guarantee savings and reduce payback periods. University leaders should support projects that enhance revenue, such as science labs tied to industry, programs with strong job placement, and housing that maintains enrollment. Education technology companies should control spending by implementing projects with districts and sharing measurable results related to attendance, completion, or tutoring success. Use higher required rates of return in internal models and reject trials that do not meet them.

Second, improve the debt structure. Spread out debt maturities so that not all debt is repriced at the same time. Where possible, protect against rate increases on the next two bond issuances rather than waiting until the last minute. Build sinking funds while job rates are still low and negotiate terms now, rather than later, while finances are good. A neutral rate slightly higher than in the 2010s will signal weaknesses in maintenance budgets and capital plans.

Third, act quickly on energy and computing needs. The BIS has noted that investments in the green transition and AI infrastructure increase investment demand. This trend will continue. Campus electricity costs are increasing as research uses large models and schools use more digital tools. Investments in microgrids, battery storage, efficient HVAC, and management of cloud costs have become financial strategies. Link each expense to a measurable result, such as reduced energy use or computer time, and fund it with savings if possible. The higher the neutral interest rate, the more valuable each saved watt and each reduced GPU hour becomes.

Fourth, prepare for trade issues. Tariffs and duties may disrupt device acquisition, lab equipment costs, and textbook supply. Schools that depend on specific imported laptops or routers will need backup options or longer timelines. Universities building labs with imported equipment should consider delivery and warranty concerns in their schedules. Purchasing departments should review contracts and include clauses that share tariff costs or permit substitutions. In times of higher rates and trade issues, preparation and standardization are very useful.

Finally, remember students and families. Higher neutral interest rates affect student loan rates, credit lines, and family mortgage payments. Tuition decisions that ignore this point will not be well-received. Match price with value by growing popular programs, expanding paid co-ops, and simplifying transfer options. Provide tuition guarantees or fixed-price degrees if possible. When families face higher financing costs, predictability is important.

We are not returning to the conditions of the 2010s. Continued tariffs, major investment in energy and computing, and larger public debt suggest a neutral interest rate that is higher than previous expectations. While policy may ease changes, the guidelines must change if the guidepost has moved. For education, this means being selective about projects, carefully managing rate risk, and reducing energy and cloud waste. It requires clear pricing decisions on tuition and creating programs that pay back quickly. It also means encouraging state and federal partners to adjust funding to reflect the new cost of capital. A higher neutral interest rate is something that needs to be adapted to. Leaders who understand it will build better campuses and school systems. Leaders who ignore it will see debt limit actions. The choice is clear, and there is still time to take it before the next event.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements. (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024.

Cleveland Federal Reserve. (2025). Neutral Interest Rates and the Monetary Policy Stance.

Congressional Budget Office. (2025). Effects of Federal Borrowing on Interest Rates and the Economy.

Dallas Federal Reserve. (2025). Plante, M. D., et al. Revisiting the Interest Rate Effects of Federal Debt.

European Central Bank. (2025). Natural rate estimates for the euro area: insights, uncertainties and policy implications.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). World Economic Outlook Update (January).

Morningstar. (2025). The Neutral Rate: What It Is and Why It Matters Now.

New York Federal Reserve. (n.d.). Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest (r-star).

Reuters. (2025, Apr. 2–11). Trump’s tariffs: announcements and implementation timeline.

Reuters. (2025, Dec. 24–30). BOJ debated need for more rate hikes; Yen strengthens as markets weigh further moves.

Reuters. (2025, Dec. 30). Fed officials showed deep divisions at December meeting, minutes show.

Comment