The Bank’s Gift to Shareholders: Why the “Capital Cut” Failed to Prime UK Lending

Input

Modified

Lower capital requirements failed to increase UK lending Banks chose shareholder payouts over new loans Capital policy without conditions does not drive growth

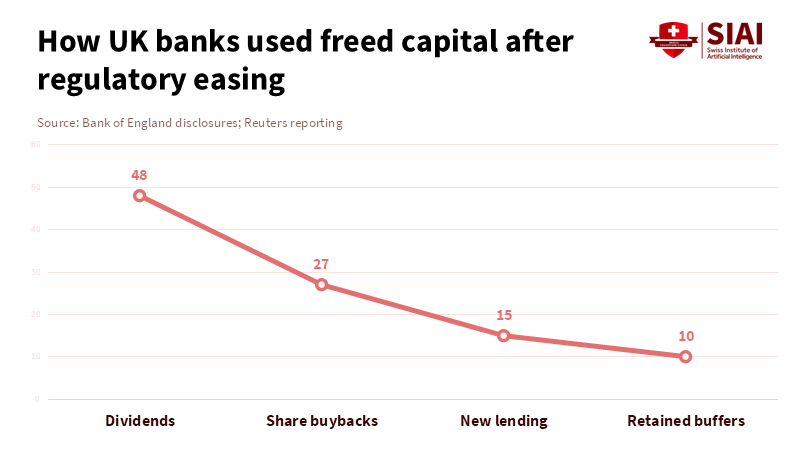

In December 2025, the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) quietly adjusted its benchmark for system-wide Tier 1 capital. The subsequent financial implications were more straightforward than the public discourse suggested. The committee reduced the formal benchmark from approximately 14% to about 13% of risk-weighted assets, immediately signaling to markets that holding equity would be less expensive. According to the Bank of England, following the reduction in the benchmark for system-wide Tier 1 capital requirements, banks chose to preserve their capital reserves and distribute some of the excess to shareholders instead of significantly increasing lending to businesses and individuals, as profitable lending opportunities remained limited and this did not result in a credit boom or notable rise in productivity. Instead, it led to higher returns for shareholders, reminding everyone that capital policy, without appropriate rules and viable incentives, gives owners the optionality rather than borrowers.

Bank Capital Policy in the UK: Examining the Discrepancy Between Promises and Outcomes

The official explanation was simple: decreasing capital requirements reduces the cost of holding equity. This enables banks to increase lending and stimulate economic growth. This argument relies on the assumptions that banks have ample safe and profitable lending opportunities and that managers are motivated to use capital to support the real economy. In actuality, neither condition was met. According to a report from the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee, the benchmark for system-wide Tier 1 capital requirements was reduced in December 2025 from around 14 percent to 13 percent of risk-weighted assets, but the report does not discuss policymakers’ expectations about credit demand, banks’ willingness to lend, or profit motives related to the benchmark change. The FPC’s adjustment indicated a shift in policy. The response to this change, however, showed that concrete constraints and credible enforcement are more crucial than simply signaling intent.

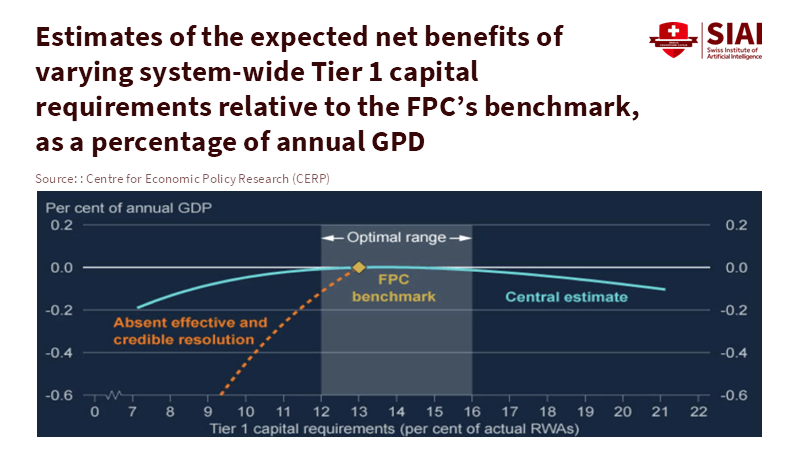

The important factor for policy is not simply decreasing a percentage on paper. It is the range of behaviors that the decrease encourages. Shareholders are not concerned with capital ratios themselves. They are interested in returns on equity. When faced with the choice between financing a marginally profitable, long-term loan and increasing dividends or buying back shares, banks often find the latter more appealing. This is especially true after a policy change that appears to lower the safety threshold. This outcome is precisely what critics cautioned. They said that decreasing capital without changing governance, risk weights, or directed lending programs would not alter bank behavior. These concerns were not unfounded. According to the Financial Policy Committee’s December 2025 report, the benchmark for system-wide Tier 1 capital requirements was lowered by one percentage point to around 13% of risk-weighted assets, equivalent to a Common Equity Tier 1 ratio of about 11%.

The Unintended Consequences of Decreasing Capital Without Complementary Measures

Banks respond to a fundamental problem: making the best decisions under uncertain conditions. They seek to maximize long-term value while complying with regulatory and market constraints. Lowering capital requirements eases one restriction. It does not change demand, collateral values, or bank management's risk tolerance. According to a December 2025 KPMG report, the UK economy saw moderate growth through the end of 2025. However, domestic demand remained weak, and consumer spending growth was sluggish due to a slowing labor market and cautious household sentiment. According to the Bank of England, net mortgage approvals for house purchases fell for the third consecutive month in March 2025, suggesting a continued decline in mortgage demand as the year progressed. Given these conditions, the additional capital was more likely to remain unused, be returned to shareholders, or be invested in safe assets rather than be used to fund new, investment-grade lending.

Even when banks have capacity on their balance sheets, lending hinges on reliable demand and acceptable risk-return trade-offs. Offering loans to small businesses, providing long-term investment lending, and managing risky working-capital arrangements are costly in terms of underwriting and oversight. If the overall economic situation is weak and potential borrowers are scarce, bank managers are more likely to maintain capital reserves and wait. This is especially true when shareholders are exerting pressure for quick returns. The Bank of England’s own stress tests and the sector’s CET1 ratios suggested resilience. Resilience, though, is not the same as eagerness. A strong CET1 ratio suggests the sector can withstand financial shocks. It does not guarantee that lenders will adjust their allocation plans if there are few viable projects to finance. The practical implication is that easing capital requirements without also reshaping credit demand or incentive systems will predictably result in decreased lending.

Solutions: Policy Adjustments to Channel Capital Into Lending

First, link capital relief to specific lending targets or reduced shareholder distributions. If regulators want to see more loans issued, capital headroom should be dependent on demonstrable increases in net new lending to specific sectors. Examples include SME term finance or decarbonization capital expenditures over a defined period. A simple, unconditional cut returns the excess capital to owners. A conditional cut turns the surplus into a tool to encourage lending. This concept is not theoretical. According to the Bank of England, when regulators introduce restrictions as part of relief measures, this can lead to changes in bank behavior, so the careful, precise design of such measures is important to ensure they are measurable and time-limited, helping reduce opportunities for manipulation.

Second, reassess risk weights and underwriting incentives. If banks find profitable, socially beneficial lending unattractive because of prevailing risk weights and internal models, simply easing capital requirements does not solve the problem. The system requires carefully set risk-weight floors for lending in key strategic categories. According to the Bank of England’s December 2025 Financial Stability Report, while there is discussion about applying lower capital treatment in situations where genuine risk reduction exists—such as with contractual revenue streams indexed to inflation or supported by public guarantees—the report notes that materially lower capital requirements could significantly reduce long-term expected GDP. Without these adjustments, banks will prefer short-term, liquid, low-return investments over long-term, productive lending.

Third, prioritize strengthened supervisory engagement and governance over reduced oversight. Any perceived gains from reduced supervision will be nullified if the market interprets it as a sign of lessened oversight. Regular, purposeful reviews that concentrate on allocation results rather than mere ratios will compel firms to explain how they intend to use additional capital. Essentially, if capital policy aims to change conduct, supervision must be the tool that enforces these changes. Critics of the initial policy pointed out that decreasing the headline requirement while simultaneously easing supervisory touchpoints would lead to passive outcomes.

Addressing Potential Counterarguments

A common argument is that banks need the freedom to absorb economic shocks and that increasing dividends supports market discipline. While this is true in theory, the relevant factor is the alternative. If the FPC intended to boost actual lending and economic growth, then the policy must be evaluated with consideration given to its capacity to change behavior within the real constraints faced by firms and banks. Capital reserves can be converted into cash by shareholders without necessarily producing lending. Another argument is that targeted measures distort markets. The reality is that the current situation already creates distortions. A capital system that treats all equity the same, even when economic structures and credit demand are unequal, will result in inefficient allocations. The correct approach involves balancing uniformity and selectivity. Allow for general resilience, but require targeted credentials for any financial relief that is presented as growth-promoting.

There is also a practical consideration. Delays in data and measurement errors make conditional capital relief challenging to implement. This issue can be resolved. Regulators already gather detailed loan-level data for stress testing and consumer protection. A concise range of verifiable metrics can be used to condition relief. Metrics could include net new lending by borrower size, term, and purpose, the proportion of lending with risk weights below a certain level, and changes in trends in non-performing loans. If necessary, pilot programs can assess the mechanism for a subgroup of banks or sectors before full implementation. The key is to align incentives, not to rely on them aligning accidentally.

The central lesson is both straightforward and critical. A capital policy that lacks binding implementation mechanisms favors shareholders while creating the illusion of policy success for regulators. If the Bank of England wants lower capital requirements to increase lending, it must view capital ratios not as abstract safeguards but as conditional instruments that require governance, supervision, and measurable lending outcomes. Current events demonstrate how technical adjustments can produce political and economic consequences that contradict a regulator’s intentions. To remedy this, policy must be designed with behavioral incentives in mind. Tie relief to lending, reassess risk weights to align with public priorities, and maintain supervision that demands clear allocation plans. Otherwise, the benefit of eased capital will serve mainly as a justification for rewarding bank owners rather than financing investment.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank of England. (2025). Record of the Financial Policy Committee meeting – December 2025. Bank of England publications.

Bank of England. (2025). Banking sector regulatory capital, 2025 Q1. Bank of England statistics.

Bank of England. (2025). Money and Credit — November 2025. Bank of England statistics.

CEPR / VoxEU. (2025). The Bank of England’s capital mistake.

KPMG. (2025). Quarterly update on UK banking / lending markets.

Reuters. (2026). Bank of England made 'capital mistake' on bank rules, former officials say.

S&P Global / Industry analysis (2025). UK banks trimming of regulatory capital requirement.

Comment