Donroe Doctrine: When ‘America First’ Becomes America’s Only Rule

Input

Modified

The Donroe Doctrine replaces global leadership with blunt self-interest Tariffs now function as leverage, not policy tools Education and governance must adjust to a less predictable order

The Donroe Doctrine isn’t a sweeping historical strategy. Instead, it describes what the U.S. is doing now. In just one year, Washington moved from threatening tariffs to actually putting them on goods from many countries—at one point, 69 trading partners were affected. Trade policy is now used to push national interests. What looks like pulling back is really a steady, deal-focused approach. Tariffs, export controls, and big investment promises are traded for quick wins, not for following old rules. This matters for schools and policy programs because controlling access changes how international academic partnerships work. The Donroe Doctrine puts immediate American interests ahead of the global order that the U.S. used to support. Education leaders need to get ready for a world where public deals replace steady, predictable standards.

Donroe Doctrine: America First, No Limits

The initial year of this policy approach was marked by a rapid overhaul of existing frameworks. Policy changes were introduced swiftly and decisively. In early 2025, tariffs were imposed on goods from neighboring countries, followed by proposals for broader tariffs on a wide range of imports. Tariff rates for specific countries fluctuated within short timeframes. Prolonged negotiations were supplanted by brief public announcements. The central development is the transformation of trade instruments into bargaining tools, with market access leveraged for immediate political objectives.

This matters for education because schools and universities rely on global connections. Labs buy supplies from other countries. Students need visas and travel to study abroad. Research partnerships depend on the free flow of goods and information. When export rules and taxes are used as pressure, supply chains can break. Equipment repairs take longer. Exchange programs get new, unexpected costs. All of this leads to more paperwork and legal questions for every department running international projects.

The prevailing narrative requires reconsideration. This shift is not merely a turn toward isolationism; it represents a transformation in engagement strategy, moving from rule-based leadership to transactional leverage. Whereas the Monroe Doctrine established regional boundaries to exclude European influence, the Donroe Doctrine employs tariffs, export controls, and selective engagement to prioritize American interests. The previous framework that facilitated alliances and international academic collaboration—characterized by open access, shared norms, and structured dialogue—has been supplanted by sporadic, deal-based arrangements. This fundamental change alters both partner incentives and the functioning of academic networks.

Taxes, Deals, and the New Toolkit

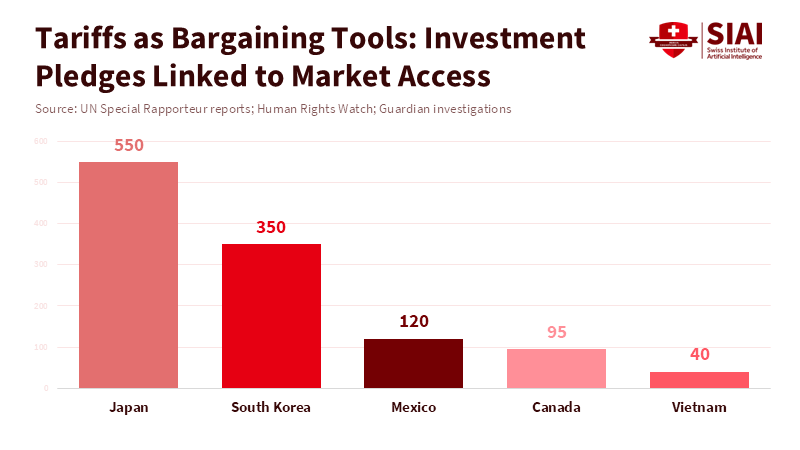

Taxes are the most obvious part of this new policy. In 2025, the U.S. made moves that changed market expectations. Early steps focused on Mexico, Canada, and China. There was talk of a general tax on all imports. Tax rates for some countries were announced, paused, and changed again. This created uncertainty for trading partners and businesses. After that, there were big deals. Japan got a package worth about $550 billion. South Korea’s deal included a $350 billion promise. In short, access to the U.S. market was traded for investment and purchase promises.

Universities experience a dual impact from these developments. First, financial costs fluctuate, as countries seeking access to the U.S. market may reduce or postpone research funding. Second, institutional priorities shift, with diplomatic agreements increasingly favoring business and strategic objectives over academic exchange. This dynamic encourages academic partnerships to focus on projects with immediate commercial value, often at the expense of curiosity-driven research that does not yield short-term national benefits.

How we gather information matters here. The numbers used here come from public statements, press reports, and official announcements. If a number is mentioned as a general promise without specific plans for how it will be delivered, it’s treated as a possible political promise rather than a sure thing. This cautious approach maintains the reliability of the evidence. The main point about policy is that when big investments are used to give tariff relief, academic partnerships risk being shaped by high-level negotiations rather than what makes sense academically in the long run.

This policy also mixes business and security issues. Sometimes export controls on AI chips were relaxed, while at other times tariffs were imposed on processors. This inconsistency makes it harder for people to follow the rules. Labs that need special processors or networking gear now have to deal with export licenses, tariff math, and political risk checks. These steps add paperwork, raise costs, and make it harder to plan international research projects.

What Educators and Policymakers Should Do

The shift from stable leadership to deal-making for leverage forces choices. Administrators need to understand their risks. They should figure out which labs and projects rely on goods that may be subject to taxes or export restrictions. They should measure the impact on their budgets. This means using simple measurements. Track how much of a lab’s equipment is imported. Track how much research funding comes from foreign companies. Track how many key employees have visas tied to foreign employers. Each of these measurements gives leaders a better understanding of how vulnerable they are.

Schools and universities should spend wisely to follow the rules. Hire lawyers who understand trade and export laws. Train staff to handle new types of international deals. These steps are important and cost much less than ending a partnership or losing a shipment of equipment.

Policymakers in education need to protect themselves rather than retreat. Expand partner networks beyond just a few countries. Create flexible program designs that can be paused without causing major problems. Fund regional data storage and cloud-based research whenever possible to reduce reliance on fragile supply routes. Create university-to-university agreements that ensure academic exchange even if national relationships become strained. These are practical ways to maintain academic continuity.

Transparency and good management are also important. Require clearer reporting on big foreign funding and have emergency plans in place if partners don’t keep their investment promises. Simple guidelines—like if more than 20 percent of a lab’s main equipment comes from risky suppliers—can trigger backup plans. Leaders and finance teams can then justify using contingency funds or quickly reallocating resources. This turns general worries into specific actions.

Finally, institutions should prioritize practical policy implementation. This includes offering targeted training for deans on trade compliance, conducting exercises to assess program resilience to disruptions, and establishing staff roles that facilitate communication between faculty and legal teams. Institutions that comprehend the implications of the Donroe Doctrine and respond proactively will be better positioned to safeguard essential research and academic exchange.

The current political environment also attracts criticism. While conditional agreements may generate tangible investments for host countries and academic institutions, the primary concern lies in their management. Publicly announced deals linked to tariff relief often result in inconsistent implementation. Large financial commitments do not guarantee timely equipment delivery, construction of new laboratories, or program sustainability. The appropriate response is not to reject all agreements, but to require clear, specific commitments with defined deadlines and to prepare for scenarios in which promises are not fully realized.

Conclusion

The Donroe Doctrine is best understood as a label for U.S. practices now dominated by the pursuit of immediate national advantage, rather than a coherent set of enduring rules. For educators and policymakers, the argument is urgent and practical: the shift to diplomacy through tariffs and quick deals undermines the foundations for stable collaboration. Instead of withdrawing, the effective response is targeted adaptation—map risks, ensure compliance, design flexibility, and invest in practical preparedness. These actions are essential to protect research and learning as national policy redefines the rules for global engagement.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. 2025. Trump clears way for sale of powerful Nvidia H200 chips to China. John Power. 9 December 2025.

Council on Foreign Relations. 2026. McGuire, C. The New AI Chip Export Policy to China: Strategically Incoherent and Unenforceable. 14 January 2026.

East Asia Forum. 2026. Miller, C. US strategy turns inward under Trump. 11 January 2026.

Economy (The Economy). 2026. Delaney, S. Trump’s ‘Donroe Doctrine’ After Ousting Maduro: A Crossroads Between Expanding U.S. Dominance and Growing China–Russia Leverage. 5 January 2026.

Economy (The Economy). 2026. Trump’s ‘Greenland Obsession’: The Real Ambition Hidden Behind the Security Rationale. January 2026.

Economy (The Economy). 2025. ‘South Africa G20’: Triumph of Multilateralism amid Trump’s Boycott, Will the World Expand Cooperation Without the U.S.? November 2025.

Reuters. 2025. Major developments in Trump’s trade war. 26 September 2025.

Reuters. 2025. Hunnicutt, T. and Katsumura, M. Trump strikes tariff deal with Japan, auto stocks surge. 23 July 2025.

Reuters. 2025. Hunnicutt, T. and Park, J. Trump says US will set 15% tariff on South Korean imports under new deal. 31 July 2025.

Comment