When Chips Become Classrooms: The Logic Behind the TSMC Japan Deal

Input

Modified

The TSMC–Japan partnership turns education into strategic infrastructure Japan converts geopolitical risk into durable industrial capacity Semiconductor policy is about institutions, not factories

Semiconductor risk used to be checked every quarter; now it’s done annually. But here’s the thing: over 90% of the world’s most important logic chips come from just one area. You wouldn’t see that much concentration in fields like energy or food, but it’s how the digital world works. The TSMC-Japan deal needs to be seen in this context. It’s not just about expanding overseas or avoiding problems. It’s a smart move to turn potential geopolitical risks into real, lasting strength. Japan’s plan isn’t just about money or quick construction. It’s about bringing together education, local government, and industry. In Japan, chip factories are becoming hubs for skills, research, and the revitalization of local communities, not just isolated factories. This shows just how important this deal is and what it could mean beyond just the chip industry.

TSMC Japan: A Plan to Spread Out Risk

The main goal of the TSMC-Japan partnership is to spread risk around more. Taiwan’s chip industry is strong because of its size, specialization, and connected suppliers. But this also creates weaknesses. As geopolitical tensions grow, companies need to expand production while maintaining their current ways of working. Many countries offer financial incentives to attract semiconductor companies to set up shop, but Japan stands out by focusing on long-term stability. The TSMC deal is built into a policy that brings together the central government, local authorities, universities, and industry players. This is important because making semiconductors requires years of knowledge that can’t be easily acquired. Without skilled workers, a factory is just an empty building.

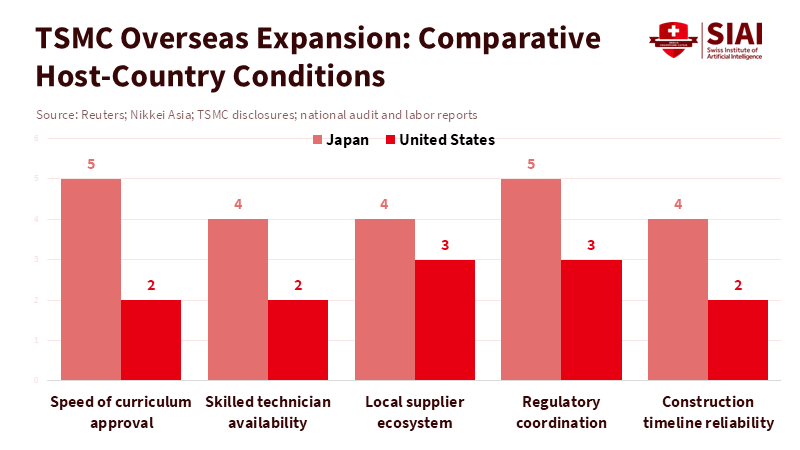

Japan is attractive because it lowers risks that aren’t about money. Getting building permits, conducting environmental studies, and improving infrastructure are faster in the U.S. than in many developed countries. More importantly, there’s strong societal agreement on manufacturing. Advanced industry isn’t seen as a nuisance but as something that brings stability to local communities. In rural Kyushu, where new factories are being built, local governments have presented TSMC’s arrival as a long-term commitment, not just a short-term economic boost. This influenced decisions about housing, transportation, and education even before production began. This leads to a smoother start-up and less uncertainty for TSMC.

This is different from other countries, where political excitement often extends beyond practical preparation. Money might secure project announcements, but it can’t replace skilled technicians and reliable local suppliers. The TSMC-Japan deal shows that the real problem isn’t money, but getting everyone to work together. By treating risk as a problem for the whole system, not just the market, Japan has positioned itself as a reliable backup in a highly concentrated global industry.

Education as a Base

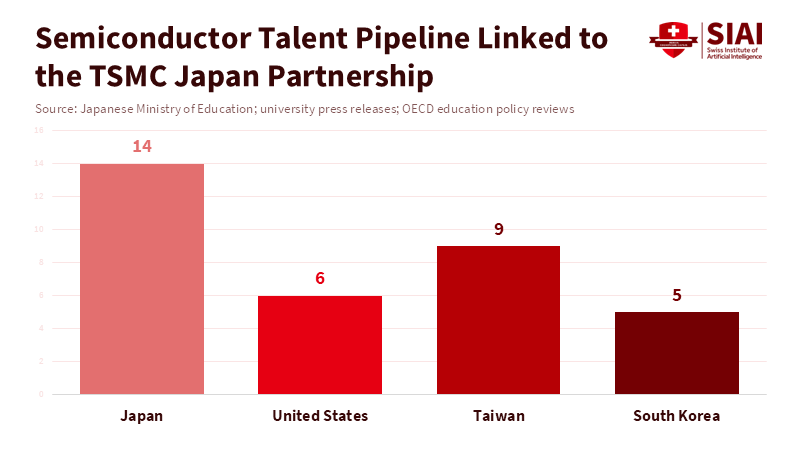

What makes the TSMC Japan deal special is how quickly the education system has adapted. Japanese universities and technical schools revised their course plans early rather than wait for a worker shortage. New programs focusing on semiconductors, practical engineering, and quick training courses were approved and started faster than ever before. This change reflects a bigger shift in how education is managed. The course approval process, often slow and fragmented, was treated as a matter of strategic importance. Government ministries, universities, and businesses all worked together with shared deadlines.

The focus has shifted to practical skills rather than just theory. The programs emphasize process engineering, equipment maintenance, and production management. These fields may not be seen as highly prestigious, but they are essential. Semiconductor manufacturing depends on many mid-skill jobs that connect research with final production. Japan saw the urgent need to rebuild this part of the workforce, prioritizing it over high-profile research achievements. This connection between education and factory operations has lowered TSMC’s training costs and improved job opportunities for graduates.

This also changes local education. Universities outside of major cities have found a new purpose. Instead of just competing for academic reputation, they have become a way into good-paying manufacturing jobs. Enrollment numbers show this change. Students who might have moved to big cities now see good local opportunities connected to global companies. This could slow down regional decline and rebalance national growth, turning education into a tool for managing where people live and work.

Importantly, the deal doesn’t limit universities to working for just one company. Semiconductor skills can be used across different suppliers and related industries. Standards in cleanroom operations, precision measurement, and process improvement are valuable beyond individual factories. By focusing on basic skills, Japan reduces the risk of becoming overly specialized. This plan makes sure that education benefits both companies and the wider economy. This balance is often missing in discussions of industrial policy, which swing between hands-off approaches and corporate control. The TSMC-Japan partnership shows another way: education that encourages adaptability rather than dependence.

Industrial Recovery and Memories of Decline

Japan’s willingness to work with TSMC stems from its history. Once a leader in semiconductor manufacturing, Japan lost its position because of disconnected strategies and strong international competition. The decline of domestic industry leaders had a lasting impact but also taught important lessons. Japanese policymakers now understand that semiconductors are essential infrastructure for the digital age, like steel was during the industrial age. Having lost ground before, they are very aware of how important this sector is.

The TSMC-Japan partnership is a practical response to this history. Instead of trying to rebuild domestic companies from scratch, Japan chose to work with the world’s leading logic chip manufacturer. This shows they understand the current market. Competing directly with established memory manufacturers would require investments and risks that most governments can’t afford. By hosting advanced logic production, Japan leverages its strengths in materials, equipment, and precision manufacturing while strengthening supply chains across East Asia.

The partnership also has symbolic importance. Japan and Taiwan have a close network of financial and social ties, unlike many former colonial relationships in the area. Trust lowers costs. This is important in an industry controlled by intellectual property, secret manufacturing processes, and long planning periods. The easy working relationship speeds up the exchange of knowledge on both sides. Japan learns about manufacturing methods developed over many years, while TSMC finds a reliable environment that fits its culture.

Some worry that depending on a foreign company might limit domestic potential. While this is a valid point, it ignores the extent to which modern manufacturing is connected. No single company or country can control the entire process. By bringing TSMC into Japan’s education and supplier networks, the partnership shares knowledge rather than keeping it exclusive. Local companies get access to standards and processes that they might not otherwise see. This improves the entire system's skills over time.

From Factories to Institutions: Key Policy Lessons

The TSMC Japan deal offers a wider lesson: industrial policy works best when it focuses on institutions rather than just individual deals. Factories are easy to see, but the institutions that support them are less obvious. Japan’s plan brings together education, regional planning, and industrial policy into one connected framework. This lowers problems and builds trust. It also creates feedback: universities change course plans based on production needs, companies adjust hiring based on graduate skills, and governments update policies based on new needs. This makes the system learn and adapt continuously.

For educators, the key is that being relevant doesn’t mean lowering standards. Instead, it means creating paths that connect education to real economic opportunities. Streamlined qualifications, flexible courses, and industry partnerships can support research goals. Management is essential; when universities are seen as important players rather than just suppliers of labor, they respond proactively.

For administrators, the partnership shows the importance of timing. Education reform often follows industry changes, but in Japan, it came first. Connecting approval processes with investment plans lowered uncertainty for everyone. This needed political will, administrative flexibility, and trust in educators to maintain standards under pressure.

For policymakers, the message goes beyond just semiconductors. As countries deal with changes in energy, climate change, and digital technology, they can use the same ideas. Money investments will fail without the right skills. Skills development will suffer without real demand. The TSMC Japan partnership shows how to connect both, turning geopolitical worries into practical plans.

Ultimately, the partnership redefines what success looks like. It’s not just about wafer output or giving out support. Success means employed graduates, revitalized regions, and stronger institutions. This is why the TSMC Japan partnership is so important. It shows how an industry under pressure can help improve education and institutional frameworks.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. 2025. “US raises India tariffs to 50 percent over Russian oil purchases.” Al Jazeera, 27 August 2025.

Centre for Policy Research (CPR). 2025. “Russia and India’s Imports of Petroleum Crude.” CPR Insights, 19 September 2025.

DGCIS. 2025. Insights into Import of Crude Oil and International Crude Oil Prices. Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics, Government of India. 24 October 2025.

Energy & Cleanair (CREA). 2025. “December 2025 — Monthly analysis of Russian fossil fuel exports and sanctions.” December 2025.

IEA. 2024–2025. India country and electricity reports and Global Energy Review 2025. International Energy Agency.

Ministry of External Affairs (India). 2025. “State Visit of the President of the Russian Federation H.E. Mr. Vladimir Putin to India (December 04–05, 2025).” Press release, 28 November 2025.

Ministry of Power / PIB (India). 2025. India’s Energy Landscape: Powering Growth with Sustainable Energy. Press Information Bureau, 22 June 2025.

Reuters. 2025. “View: Trump order imposes additional 25% tariff on goods from India.” 6 August 2025; and related coverage on tariff impacts, August 2025.

The Guardian. 2025. “Putin and Modi to meet amid politically treacherous times for Russia and India.” 4 December 2025.

World Bank. 2025. “Reinvigorating India’s Electricity Distribution for Access, Reliability, and Digitalization.” Project summary, July 2025.

Comment