The world will not long survive if state kidnapping becomes routine — and educators must lead the reckoning

Input

Modified

State kidnapping replaces law with power and turns exceptional force into dangerous precedent When rules bend for one state, they fracture for all others Without firm legal boundaries, global order gives way to permanent instability

The apprehension of a sitting president by a foreign nation constitutes a crucial juncture, testing the principles of law, legitimacy, and order when a prominent democracy chooses coercion over established procedures. The hypothetical capture of Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces in January 2026 prompts an important question: How should we characterize a situation where a country crosses borders to detain a rival leader? The term state kidnapping aptly describes the action and sparks debate about its implications.

Allowing such seizures to be considered acceptable tools of statecraft would undermine formal international agreements, established norms, and reciprocal constraints. This situation would have practical consequences for educators and administrators, as classrooms, accreditation systems, and exchange programs depend on predictable regulations. The replacement of rules by raw power would require rapid adjustments to curricula that teach civic trust, human rights, and international order in order to safeguard the social contract that schools both reflect and reinforce.

State Kidnapping and the Collapse of Legal Restraint

State kidnapping encompasses a range of actions, including clandestine renditions, cross-border raids, and the removal of political figures without the consent of the host state. These acts are not new. According to a Harvard Law article, the U.S. raid that led to Osama bin Laden’s death in 2011 is often cited as an example of Washington acting alone on foreign territory. Views on the raid varied at the time, with some describing it as an act of self-defense based on Article 51 of the U.N. Charter, while others warned it could set a precedent for violating another nation’s sovereignty. The bin Laden episode demonstrated the ability of a powerful nation to bypass multilateral procedures and assert legitimacy based on the situation on the ground. This decision yielded short-term political benefits but caused long-term diplomatic friction and left unresolved the question of when power supersedes law.

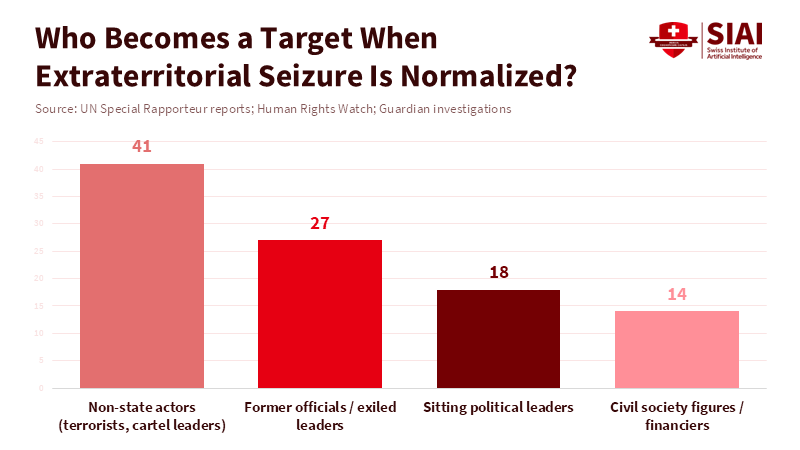

The Maduro case heightens this dilemma. Regardless of the moral judgment on Maduro’s alleged offenses, the seizure was carried out without explicit multilateral consent and was presented as both punishment and regime change, a conjunction that can be destructive. When a government disregards judicial procedure, other governments may feel justified in doing the same to figures they consider illegitimate. The risk is symmetrical: a populist leader in Washington might target Caracas today, but tomorrow an authoritarian regime could target a democratically elected rival in Taipei, Pyongyang, or another location. Reciprocity then leads to a tit-for-tat dynamic, replacing rule-based restraint and creating not just unstable diplomacy but a normalization of coercive removals as policy tools rather than emergency exceptions.

From Exceptional Acts to Systemic Risk

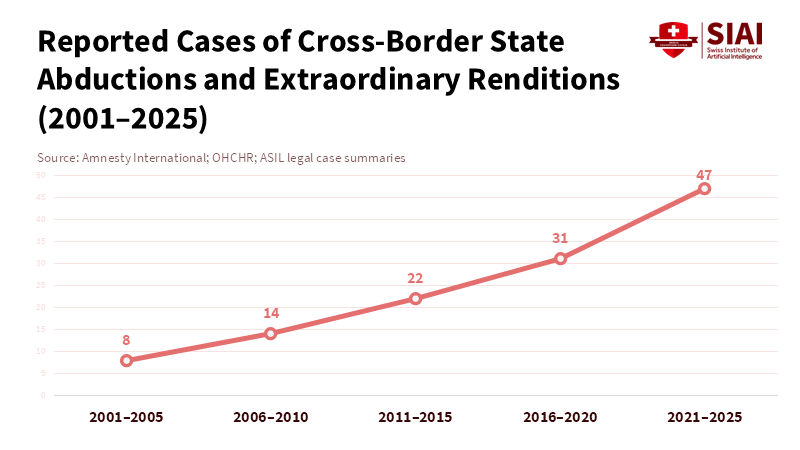

The framework of international law possesses inherent limitations. Extraordinary renditions, secret detentions, and cross-border operations have long been part of statecraft, accepted as rare and deniable anomalies. When such actions become overt, extensive, and unconditional, they cease to be marginal practices and become central systemic risks. Weak states and fragile institutions are especially vulnerable. The effects extend to universities and schools, where scholars abroad face increased risks, students from concerned countries lose safe exchange opportunities, and campus research collaborations become entangled in geopolitical risk assessments. Educators must recognize that legal norms are not abstract but serve as the essential framework that sustains civic life; their erosion will change both the content and purpose of civic education.

To address the normalization of state kidnapping, classrooms must emphasize how institutions and practices sustain trust, going beyond merely teaching international law content. This begins with curricular changes that prioritize institutional design, procedural safeguards, and transnational accountability. Future public managers must recognize the broad implications of extralegal actions, including frozen exchanges, research collaborations, and the effects on academic freedom. Recent studies on transnational repression reveal a rise in cross-border threats against dissidents and scholars, which is a vital concern for universities engaged in global exchange. Neglecting these trends in civic education would leave students unprepared to repair institutions when needed.

Administrators must convert these curricular adaptations into immediate policy changes. Offices of international affairs should adopt risk assessments that account for potential political abduction scenarios. According to Stanford University, memoranda of understanding should include a clear statement clarifying that the agreement is not legally binding. Teaching methods must evolve, moving beyond simulation exercises that address only budget shortfalls or natural disasters to encompass scenarios involving a partner government facing extrajudicial action. Schools act as civic laboratories and must rehearse the defense of rule-based cooperation to be ready when those rules break. The existing data is a cause for concern: international human rights bodies and research institutions have noted a growing number of transnational pressure tactics and acts of violence in 2024–25, threatening academic exchange and safety.

Addressing this pedagogic requirement involves more than a single seminar; it seeks to restore a cultural reflex for process. Students must practice procedural humility, verify sources, adhere to institutional channels, and build coalitions across sectors. This training benefits diplomats, lawyers, journalists, NGO workers, and technologists, whose actions amplify or constrain political responses. Educating effectively leads to a generation that values legitimacy as highly as results, preventing a scenario where legitimacy defers to those who act first, a detrimental outcome for societies that depend on predictable regulations to manage complex human projects.

Restoring Boundaries Without Rewarding Impunity

The legal debate on cross-border captures usually divides along lines of necessity and remedy. Supporters argue for necessity, saying that standard processes cannot address all threats, while critics focus on remedies, noting that extra-legal captures undermine accountability and invite retaliation. While both sides have valid points, policy should prioritize system integrity through tangible reforms that lessen the incentives for state kidnapping while maintaining legitimate, lawful tools for states to address transnational crime. Initially, there is already strength in rapid multilateral procedures for urgent prosecutions. An emergency channel within existing international institutions could allow verified, time-limited authorizations to chase high-risk suspects across borders, accompanied by prompt oversight and post-action review, preserving speed and legitimacy. Existing international law includes provisions for exceptional measures; making these measures predictable and responsible would reduce the justification for unilateral seizure.

There's also the expansion of legal and economic deterrents for states that already conduct public, unauthorized captures. Sanctions and criminal referrals have limited effectiveness when applied against powerful states, but tiered actions—joint suspensions of high-level exchanges, targeted freezes against responsible agencies, and aligned legal actions in neutral settings—can raise the political cost of extralegal actions. It would be beneficial to bolster protections for academic and civil society mobility through existing bilateral and multilateral safe-harbor agreements. Universities could declare safe enclaves and get rapid international legal backing if staff or students face transnational threats. These tangible measures help keep research and learning viable. Current institutional reports show that governments and civil society are documenting rising cross-border repression and are proposing policy tools, providing momentum to immediately build formal mechanisms.

Some argue that emergencies demand flexibility, while others claim that some leaders exploit state weakness to hide behind sovereign immunity. That is true, but flexibility differs from impunity. Creating legal space for urgency, with a rigorous and reviewable process, addresses concerns by allowing states to act when demonstrable harm is imminent and offering a clear remedy path if action is mistaken or illegal. A transparent emergency mechanism would also cut perverse incentives for clandestine deals with third parties, shady renditions, or privateer operations. An international society seeking to preserve order must create processes that are faster than coercion but slower than summary force, because the substitute creates a politics of spectacle, in which the first actor rewrites the rules through ambition.

Change must begin with institutions that shape civic understanding, as is commonly known. Universities should mandate modules on institutional resilience in professional degrees, connect legal clinics with rapid-response fellowships to advise campuses and civil society on transnational threats, and create public archives that document cases of cross-border force so students learn from facts rather than politics. National policymakers should establish a UN or regional body task force to draft an accountability protocol during emergencies. That protocol wouldn't remove the need for judicial process, but it would accelerate evidence-based cooperation and ensure post-action review. Civic educators have a unique role here: to teach the rules supporting cooperative life. When the rules fall short, they must lead repair talks.

Functional real tools matter. Negotiate legal templates in advance to provide swift legal aid during high-risk events. Upgrade campus security by adding diplomatic liaisons and legal hotlines. Provide free training for public managers on assessing when an extraterritorial event is lawful versus when it amounts to essentially a kidnapping at the state level. The goal is to make doing things lawfully simpler than by force. Even if good results are not a guarantee of reforms, they do lower returns from one-sided pressure and create more obvious aftermaths once the lines are passed. Where law and order are at their peak, social orders are secure, and educational platforms become more agile.

The capture of Nicolás Maduro tests rather sovereign power substitutes procedure. As “state kidnapping” renews as a pattern, we will witness rules in flux and doubt spreading fast. Educators cannot be unbiased through that change because we teach methods ensuring social stability: carefulness, deliberation, and facilities that channel altercations within predictable procedures. It is time we reimplement such methods through curricula, practical campus drills, and public policy. The preference is clear: make urgency operate legally, or expect force to occur routinely. Failure is costly, especially given how simple the alternative is, and it has significant fallout, including exchange cancellations and a weakened public life. By acting, educators can shift facilities again towards a smooth procedure. Without acting, the classroom is the first teaching ground for such terrible changes.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. (2026). Abduction of Venezuela's Maduro illegal despite US …

Amnesty International. (2025). The State of the World's Human Rights: 2025.

AP News. (2026). AP obtains documents showing Venezuelan leader Delcy Rodríguez has been on DEA's radar for years.

ASIL (American Society of International Law). (2011). Pakistan's Sovereignty and the Killing of Osama Bin Laden.

European Parliament. (2025). Transnational repression of human rights defenders: The impacts on civic space and the responsibility of states.

Guardian. (2026). Deposed Maduro pleads not guilty after capture in shock …

Harvard Human Rights Journal. (2020). Weissbrodt, D. Extraordinary Rendition: A Human Rights Analysis.

OHCHR / UN reports. (2025). Transnational repression brief and related statements.

Oxford Public International Law. (n.d.). Article 2(4) and use of force; international legal frameworks.

Parliamentary Research Briefing (UK). (2011). Killing Osama bin Laden: has justice been done?

Scotusblog. (2026). Maduro's arrest places these Supreme Court rulings in the spotlight.

Comment