Is the AI bubble real? A sober read of value, feedback loops, and systemic risk

Input

Modified

AI investment looks inflated, but much of its value is already embedded in real productivity gains Profits and adoption show substance, even as debt and feedback loops create fragility The real policy challenge is managing systemic risk without mistaking transformation for a bubble

The idea that we're sitting on a massive bubble is catchy, but is it true? The prices of some AI-related stocks have jumped like crazy in just a few months, and building data centers is costing a fortune. New companies are spending tons of money on AI models and people. However, studies show that AI tools are already able to do tasks worth about $4.5 trillion in the United States. This isn't just wishful thinking; it's what AI can handle right now. If machines can do or help with that much work, then the value of AI companies might be based on more than just speculation. It could mean the economy is changing. But these changes aren't always smooth. Many companies borrow too much to grow, and some fail. The main question is whether these real benefits, along with risky, debt-fueled investments, will create a shaky system or a lasting change.

What is an AI Bubble and Why should we care?

The word bubble can be misleading. It usually means that prices are too high compared to what something is really worth. In this case, it's hard to say what AI is truly worth because it depends on current profits, future improvements, and things like data, worker training, and cloud computing.

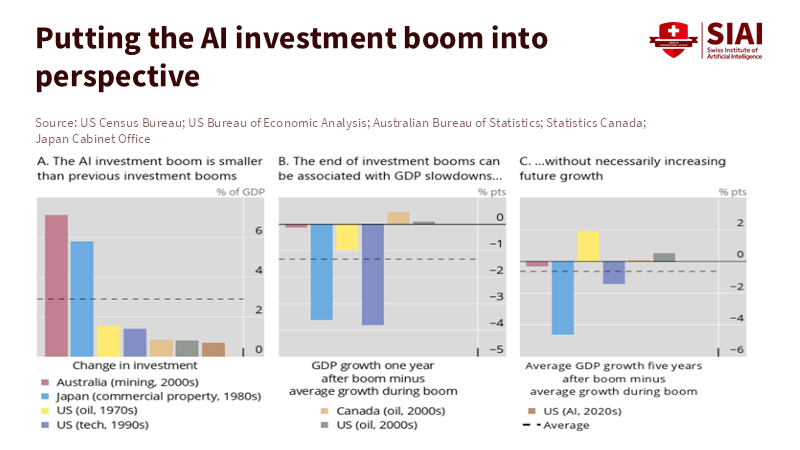

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has a helpful way of looking at it. When a technology boom is funded by both company profits and loans, it can change the economy. Loans increase the risk that problems with overvalued companies could spread to the credit market. According to a 2026 article from the Bank for International Settlements, taking on debt does not automatically indicate a bubble, but it can increase risks if companies make mistakes. In the AI sector, many established firms are using AI to reduce costs or enhance their offerings, while new companies often depend on ongoing investments and increasingly turn to debt financing as their needs grow. The challenge for leaders is to distinguish between risks to the whole system and the normal ups and downs of a changing market.

This is important for educators and leaders because the impact isn't just about money. If companies start cutting jobs or outsourcing tasks quickly, schools and training programs need to adapt. This is a chance to make education more flexible, focusing on specific skills instead of rigid job titles. But this requires money, time, and changes to the system. If the market crashes, there might be less support for retraining, even though it's needed more than ever. So, how the AI bubble plays out is key to how we plan education and support systems.

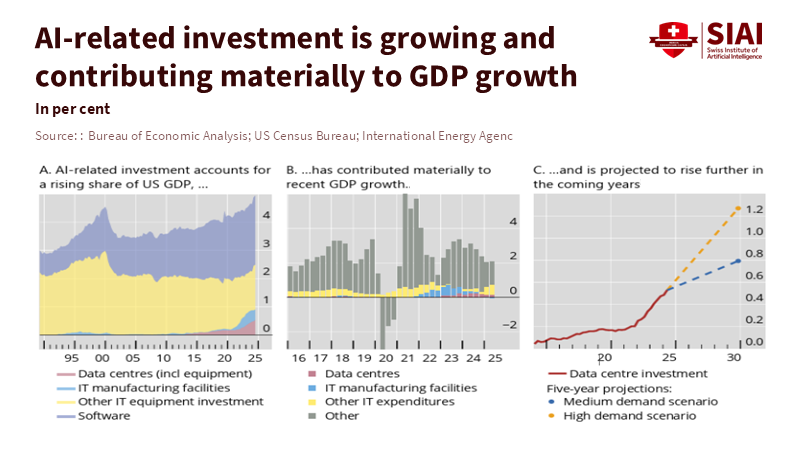

The Numbers about the AI Bubble

Here are three things to consider: (1) how much of the economy AI can actually reach; (2) how the market values AI suppliers (like chip makers and cloud providers) and their profits; and (3) how the AI sector is being financed.

First, studies suggest that AI could soon affect trillions of dollars in the economy. McKinsey estimates that AI could add $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion globally in the coming years, which is close to the $4.5 trillion figure mentioned earlier. These numbers aren't a guarantee, but they're possible if AI is adopted, well-regulated, and used in smart business models. They suggest that AI's value might be based on real productivity gains rather than just hype.

Second, let's look at suppliers. NVIDIA's recent success shows that they're making a lot of money from data center GPUs and AI demand. This is important because it shows that some parts of the AI industry are turning technology into real cash. Companies that sell the hardware and infrastructure for AI are being paid by companies that want to build AI capabilities now. This makes it less likely that the AI boom is pure speculation.

However, there's a concern that some of the money these suppliers receive is used to buy more of their own products, making it hard to tell whether their profits are driven by real economic demand or just internal cash flow. The truth is probably somewhere in between: strong supplier profits suggest real demand, but repeated internal purchases can inflate revenues and valuations in the short term.

Finally, how AI is financed is important. The BIS analysis shows that rising debt in a new sector can make the whole system more vulnerable. Many AI startups need substantial capital because computing power, engineers, and data licenses are expensive. If investors put debt or expensive capital into companies that can't soon turn a profit, the correction could be harsh. But if the AI sector creates real value by automating tasks worth trillions, bankruptcies are possible without the whole economy collapsing. The real risk is when financing is concentrated in a few highly indebted companies or when big banks are heavily exposed. So, the key question is not whether there's a bubble, but how fragile the financial structure supporting AI expansion is.

Two Claims from Tech Leaders

Tech leaders have two main arguments against the idea of an AI bubble. First, they say AI is already changing how work is done, and that high valuations simply reflect the productivity gains investors expect. They point to changes in workflows, user behavior, and cost structures across companies. The World Economic Forum and other analyses show that AI tools are already capable of handling many tasks. If AI can do or help with tasks worth trillions, then much of its market value is based on real potential, not just empty promises.

Second, tech leaders point to strong demand. Major companies aren't buying chips just for show; they need them to deploy AI models that improve their profits or products. This demand has led to big contracts between cloud providers, chip makers, and AI companies. In this sense, revenues at suppliers like Nvidia aren't just internal money flow. According to McKinsey's Global Payments Report, payments form a crucial part of the supply chain, serving end users such as banks, retailers, and healthcare providers who anticipate returns, even as concerns about internal cash flow persist. Some deals are structured in ways that firms buy services from each other or related parties, which can inflate valuations without increasing overall economic output. The challenge for leaders is to detect when these structures dominate capital flows and to adjust financial regulations accordingly.

Overall, these arguments complicate the bubble narrative. The presence of real use cases and strong supplier revenues suggests more reality than a classic speculative mania. But the concentration of gains, the capital intensity of buildout, and unclear deal structures create the fragility highlighted by the BIS analysis. The result is a mix: substantial real value combined with boom-era financing patterns that could resemble a bubble under the wrong conditions.

What This Means for Educators, Administrators, and Leaders

First, for educators: AI is changing the demand for skills more than it's eliminating jobs. This means that education should focus on breaking down jobs into tasks and teaching the right mix of technical, judgmental, and interpersonal skills that complement automation. Short, flexible credentials that map to task portfolios will be more important than certificates tied to a specific job title. Public funding should support adult learning and employer-led apprenticeships that make it easier for workers to move to new roles. If policy waits for a market correction before acting, retraining budgets will be smaller, and social costs will be higher.

Second, for administrators in universities and schools, investments must be lasting. This means building partnerships with local employers to design microcredentials and ensuring that credits can be transferred. It also means expanding career services for mid-career learners and collecting data to track actual job-market outcomes. Investing in quick, one-off bootcamps will help some people, but it won't be fair to everyone. Systems that link credentials to clear employer needs will reduce mismatch and produce better social returns, especially in regions that depend on industries vulnerable to automation. Leaders should encourage these links by funding and tying performance metrics to employment outcomes.

Third, for financial and regulatory leaders: the goal is to limit systemic risk while allowing useful capital to flow. This requires two things: better data on large AI firms and their financiers so regulators can map credit risks, and financial regulations that address new risks. Stress tests should include sudden drops in AI project valuations, and there should be limits on correlated lending to the same collateral class (like specialized data centers). According to the Financial Stability Board, strengthening the resilience of non-bank financial intermediation is essential to prevent the failure of a few highly indebted firms from triggering broader credit problems. While such measures do not halt market changes, they help reduce the risk that a correction could severely impact education budgets and social safety nets just when labor markets need support.

Addressing Concerns

Some worry that counting potential task coverage overstates value because adoption is costly and uncertain. That's true. Task mapping shows what's technically possible, not guaranteed results. Others argue that supplier profits (like Nvidia's) may reflect short-term scarcity rather than lasting returns. That's also true: profits driven by tight supply chains or limited wafer capacity can decrease as competition or supply increases.

Therefore, we need to look at three things: realized profit streams at suppliers, observed productivity gains in adopters, and the quality of financing structures supporting the sector. According to a recent OECD warning, if all three indicators—market valuations, financing, and adopter returns—are positive, high valuations are less likely to signal a pure bubble. However, when only valuations and financing are elevated, and adopters show mixed or negative returns, it points to a classic bubble scenario. The OECD notes that more comprehensive public data is needed to properly measure these risks. We should start with mandated disclosure of contracts and revenue sources for very large AI firms, and with clear reporting by banks on loans to the AI sector. Productivity experiments should be part of public research programs so that the returns to specific AI deployments can be audited independently. Administrative data should be used to follow employment transitions by task composition. These steps are significant but feasible. They shift the debate from slogans to signals and let policy act on real risk rather than on fear.

In conclusion, we should act on risk, not hype. The system is neither pure bubble nor pure bonanza. There is real technical reach (measured in trillions of dollars of task value) and real commercial translation (visible in supplier profits and enterprise contracts). These facts weaken the claim that the whole thing is a speculative house of cards. Yet the financing patterns flagged by BIS and the concentration of gains increase risk to the system. For educators, the key is to prepare for task-level change, not for a one-time job swap. For administrators, it's about building flexible, employer-linked learning at scale. For leaders, it's about mapping risks and adjusting financial regulations so that needed capital can flow without endangering the system that funds education and social insurance. If we do that, we move from a simple debate about an AI bubble to a practical program that protects people while unlocking real gains. The choice is not between optimism and worry; it's whether we will measure, manage, and educate with the seriousness this moment demands.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aldasoro, Iñaki; Doerr, Sebastian; Rees, Daniel. 2026. Financing the AI boom: from cash flows to debt. Bank for International Settlements Bulletin No. 120. 7 January 2026.

McKinsey Global Institute. 2023. The economic potential of generative AI: the next productivity frontier. McKinsey & Company. 14 June 2023.

NVIDIA Corporation. 2025. NVIDIA Announces Financial Results for Fourth Quarter and Fiscal 2025. NVIDIA Investor Relations. 26 February 2025.

Simone Crymes (Cognizant). 2026. “AI isn’t a bubble — it’s $4.5T worth of work ready to scale.” World Economic Forum, January 2026.

CNBC. 2026. “Are we in an AI bubble? What 40 tech leaders and analysts are saying.” CNBC feature, 10 January 2026.

Comment