When Science Meets Doctrine: What the Data on abortion bans and infant health Really Shows

Input

Modified

Abortion restrictions are linked to higher infant mortality and worse maternal health outcomes Research also shows increased relationship violence and long-term harm to children Policy debates must account for these documented effects, not ideology alone

More infants die when abortion access is removed. In states that moved to near-total bans after June 2022, infant mortality rose by roughly 5–6 percent above what experts expected—an increase concentrated among babies with congenital anomalies and in already-vulnerable groups. These are not abstract numbers; they are lives and families harmed by policies that change medical practice and the timing of care. The phrase abortion bans and infant health names a clear, measurable link: when pregnancies that would previously have ended safely are carried to term, neonatal outcomes shift—more premature births, more deaths tied to congenital conditions, and more infants entering childhood with acute medical needs. It reframes debates that often pivot on moral absolutes by asking different questions: what do contemporary datasets reveal about concrete harms, and what practical steps should educators, administrators, and faith leaders take when policy decisions yield predictable public-health consequences?

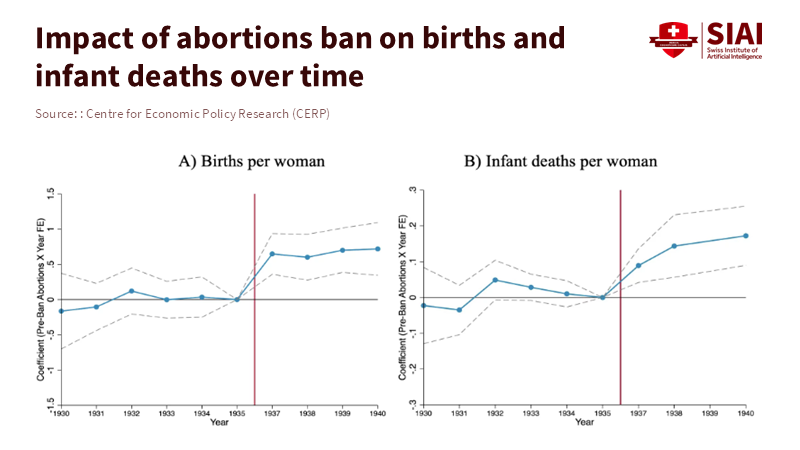

Abortion bans and infant health: the immediate empirical picture

The clearest short-term signal comes from recent U.S. studies comparing states with strict limits to those without them. High-impact journal analyses document small but meaningful rises in infant deaths and deaths from congenital anomalies after bans. One multi-center analysis estimated infant mortality rising from 5.93 to 6.26 deaths per 1,000 live births in affected states—a roughly 5.6 percent increase. That matters because it reverses decades of decline and is concentrated among infants born to parents already facing structural disadvantages: younger or less-educated mothers and marginalized groups. These patterns strongly suggest that limiting termination changes which pregnancies are brought to term and, therefore, which infants enter neonatal care.

The mechanism is visible in clinical data: when abortion access is constrained, pregnancies with severe anomalies that would previously have been terminated are more often carried to viability. Neonates with serious congenital problems have higher rates of prematurity and early mortality; NICUs see higher acute care needs; hospitals experience a shift toward frailer newborns. Separately, some research shows modest overall increases in fertility after bans, altering population risk profiles for infant health. Neither moral framing nor rhetoric alters outcomes; restrictive laws change who gives birth, reflected quickly in health data.

Abortion bans and infant health: maternal risk, family violence, and social harm

Infant outcomes cannot be disentangled from maternal health and safety. Globally, unsafe abortion remains a preventable cause of maternal mortality and morbidity; international agencies estimate that tens of thousands of people die annually from complications when safe services are inaccessible, and millions more are hospitalized. Where legal access narrows, clinicians and public-health systems expect more cases of unsafe or delayed care—and with them, higher maternal risk. In the U.S. context after 2022, researchers forecasted and observed increased maternal morbidity and stressed emergency services, especially in regions without ready cross-state access. These maternal harms ripple to newborns because pregnancy complications and delayed care raise the odds of preterm delivery and neonatal complications.

A separate evidence strand links restrictions to rises in intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion—conditions that make pregnancies more dangerous and unwanted births more likely. Recent economic analyses find that states enacting strong restrictions saw an uptick in reported intimate companion violence—estimates cluster around 7–10% increases attributable to tightened access. The causal logic is credible: when a pregnant person cannot terminate a pregnancy, she may be forced to remain in a coercive relationship longer, and delays, travel burdens, and financial strain exacerbate conflict and exposure to harm. These social dynamics impact infant outcomes: children born into violent or scarce-resource households face higher risks of neglect, poor health, and worse developmental trajectories. For anyone concerned with child welfare, these facts demand policy attention.

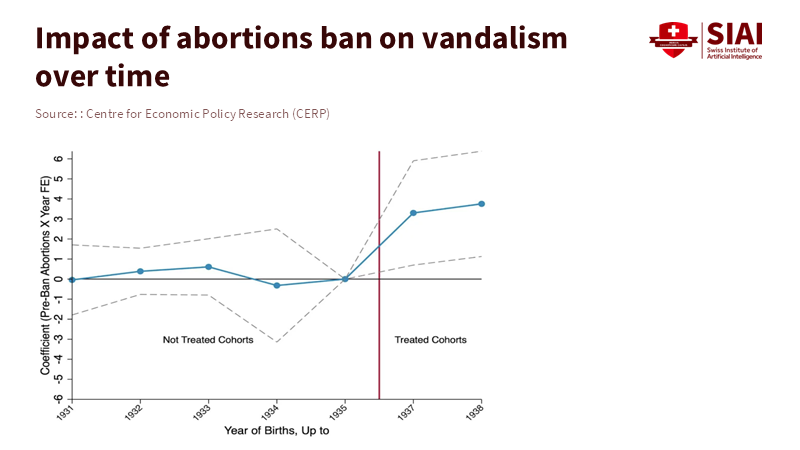

Abortion bans and infant health: long-term echoes and lessons from history

Historical episodes show that the consequences of restrictive reproductive policy extend far beyond the nursery. The Romanian case under Ceaușescu’s 1966 ban is often cited because it produced a sudden, large increase in fertility. Researchers who tracked cohorts born during and after the ban found worse health at birth, higher abandonment rates, and later life disadvantages in education and earnings for those children—effects that weigh on social mobility and public budgets for decades. That lesson is not abstract: when policy forces births that families are unprepared for—economically, medically, or socially—the costs do not evaporate after the neonatal period. They accumulate in school systems, welfare programs, and public health expenditures.

At the same time, nuance matters. Not every restriction produces identical results; the size and nature of harms depend on the presence of exceptions, access to prenatal care, the ability to travel for services, and the robustness of social supports. Yet even generous exceptions (for fetal anomaly, rape, or maternal health) can be hollow in practice if the legal process to qualify is onerous or if reporting requirements deter survivors. The empirical pattern across time and space is consistent: where access to safe termination falls, certain predictable harms emerge—increased infant mortality in specific subgroups, higher maternal risks, and social dynamics (like greater intimate partner violence) that compound harm. Those are the measurable tradeoffs that must be weighed against moral positions in public policy.

What educators, administrators, and faith leaders need to know and do

Educators and school leaders often meet the consequences first. Public schools and universities will see more births among students and more children with unmet health needs. Administrators should audit student-parent supports, ensuring clear counseling pathways, flexible attendance policies for parenting students, and links to community health services. Nursing and school-based health programs must be resourced to identify and treat vulnerabilities early; early intervention programs save money and human potential later. These pragmatic steps honor diverse moral views while reducing predictable harm to children.

Faith communities and pastors who oppose abortion on doctrinal grounds still face moral choices about stewardship of children and families. If policy choices lead to more infants born into precarious households, congregations can respond with concrete supports—parenting classes, emergency funds, healthcare navigation, and non-judgmental counseling. The political posture of a religious community does not absolve it from the material outcomes of public policy. Those who advocate for legal prohibition should also propose scalable supports that mitigate demonstrated harms; otherwise, they ask society to absorb the costs without a plan. Policymakers, meanwhile, must measure and report outcomes: laws with moral aims should be evaluated for their real-world effects and adjusted if they produce demonstrable harm to infants and mothers.

Policy tradeoffs, data transparency, and practical reforms

Policy debate often treats abortion access as binary. The data invites a different framing: which legal arrangements, exceptions, and implementation details minimize harm while respecting plural views? Three reforms deserve priority. First, ensure transparent monitoring of perinatal and maternal outcomes at the county and state levels so policymakers can see early signals and respond. Second, remove procedural barriers to exceptions that, in practice, deny care; if an exception requires police reports, it may be functionally meaningless for survivors who fear reporting. Third, bolster social and neonatal supports where restrictions are in place—expanded Medicaid for pregnant people, funding for NICUs serving high-need populations, and investments in maternal mental health. These are not panaceas, but they address the documented channels linking abortion bans and infant health.

Anticipating critiques: opponents will argue that admitting these data concedes too much ground to a pro-choice stance. But the opposite is true. Presenting clear evidence about outcomes creates better moral deliberation. It asks religious leaders and legislators to weigh their values against real harms rather than rely solely on dogma. For those who value life, the relevant question becomes: how do we reduce infant and maternal suffering when policy changes the volume and vulnerability of births? The pragmatic answer is not silence; it is careful design and accountability.

If policymakers insist on restrictive laws, they must also accept the empirical ledger that follows. Recent, high-quality studies show measurable increases in infant mortality, shifts toward more premature births and congenital anomaly–related deaths, and social harms such as higher intimate partner violence after limits on abortion access. These are not partisan talking points; they are outcomes we can count, measure, and act upon. For educators, administrators, and faith leaders, the humane response is practical: audit needs, expand supports, and insist that laws be paired with transparent outcome monitoring. For legislators, the ethical duty is the same: if a law reshapes births, legislate with the data in view and fund the services the law will require. Facts do not settle every moral dispute. They do make the costs of particular choices clearer. Those costs demand plans, not platitudes.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bell, S.O., et al. (2025). US Abortion Bans and Fertility. JAMA Reproductive Health.

Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières. (2024). Unsafe abortion: A preventable danger. MSF Briefing.

Gemmill, A., et al. (2025). US Abortion Bans and Infant Mortality. JAMA.

Pop-Eleches, C. (2002). The Impact of an Abortion Ban on Socio-Economic Outcomes of Children: Evidence from Romania. Columbia University Working Paper.

Srinivasulu, S. (2025). How Will Abortion Bans Affect Maternal Health? Journal of Women’s Health.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2024). Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended—a global crisis. UNFPA Press Release.

Northeastern University / Erten, B., et al. (2025). Abortion bans and intimate partner violence: Evidence from post-Dobbs. NBER Working Paper / Northeastern Research Summary.

Time Magazine. (2025). Abortion bans worsen relationship violence, study finds. Time.

Reuters. (2025). Infant mortality rises in states with abortion bans, study finds. Reuters News.

World Health Organization. (2025). Maternal mortality: Key facts. WHO Fact Sheet.

Comment