When Trade Moves but Value Does Not: Reallocation, Rerouting, and the Illusion of Export Growth

Input

Modified

Many trade gains reflect rerouting, not real production Reallocation builds domestic value; rerouting only shifts routes Policy must target value added, not export volume

The main takeaway is that much of the recent growth in Southeast Asian exports to the U.S. is due to goods passing through the region, not from actual increases in local manufacturing. From 2018 to 2024, several countries doubled their share of certain U.S. imports, but only a few saw real gains in domestic value added. This distinction matters for policy. If policymakers confuse rerouting with real industrial growth, they could miss out on lasting economic benefits. Acting as a middleman creates only limited and unstable jobs, tax revenue, and supply-chain strength. In contrast, export growth driven by local production brings longer-lasting benefits. It's important to know whether a country is building real industrial capacity or just acting as a transit point for long-term policy success.

Trade: What Reallocation and Rerouting Truly Entail

Trade reallocation occurs when a country significantly increases its ability to produce goods. This means building new factories, upgrading old ones, and helping local suppliers grow. As a result, workers earn more and develop better skills. Signs of reallocation include more domestic value added per export, more foreign investment in actual production, and stronger ties to local suppliers. Over time, this reduces the need for imported parts, leading to higher wages and better productivity.

In contrast, trade rerouting is mainly about moving goods through another country for legal or logistical reasons. The products are still made in the original country but are shipped elsewhere to avoid tariffs or take advantage of better trade rules. Rerouting appears as higher export numbers without a real increase in local value added. The main benefits are limited to warehousing, paperwork, and minor assembly or repackaging. While rerouting can boost export figures, it rarely creates many manufacturing jobs or strong supply networks. These two processes require different policy responses. Reallocation needs industrial policies and workforce training, while rerouting requires better customs checks, trade compliance, and investment in ports. Recent analysis highlighted the importance of not confusing these two types of export growth.

To figure out which process is happening, it's important to look beyond total export numbers. A practical way is to analyze value added, which shows how much of the value of an exported good is created within the country. If the domestic share increases along with total exports, reallocation is likely. If total exports rise but value added per unit stays the same or drops, rerouting is more likely. Collecting data from businesses to track supplier networks and ownership, along with customs data on re-exports, can help. These assessments are key to making policy decisions. Countries seeing reallocation can invest in vocational training, industrial parks, and export-related research and development. Countries focused on rerouting should tighten trade documentation, renegotiate rules of origin, and invest in higher-value logistics services.

Trade Reallocation and Rerouting: Evidence from Six Southeast Asian Countries

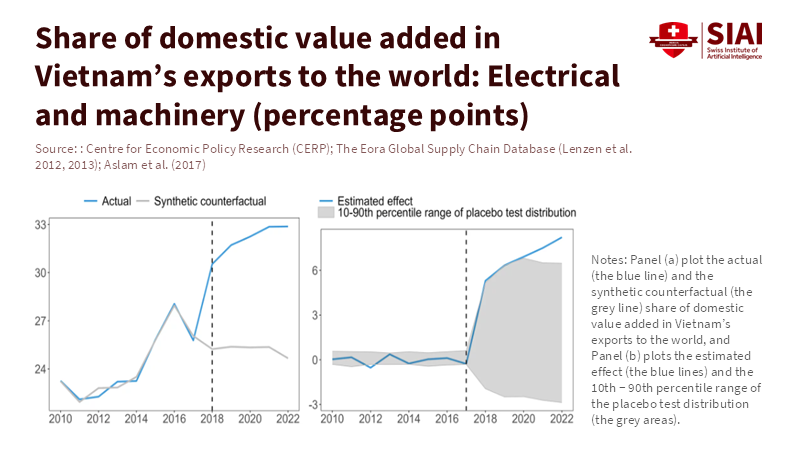

To show how these processes work, look at six economies often grouped together when talking about China-like growth: Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore. Vietnam’s numbers stand out. Electronic exports have grown quickly, and investment in contract manufacturing has increased. However, a closer look at the data shows a mixed picture. There is strong reallocation in some areas of electronics assembly, but also significant rerouting in low-value exports that still depend on Chinese content. In short, Vietnam is building real capacity while also serving as a transit point, so policy should reflect both roles.

Indonesia presents a different picture. Its large domestic market and resource base make it suitable for reallocation in areas such as processed commodities and emerging domestic electronics assembly. Protectionist measures and local-content requirements, though, can cause distortions. When companies meet local-content targets by simply routing components through secondary suppliers or doing minimal local processing, the gains may be superficial. Indonesia's total export figures, which reached hundreds of billions of dollars in 2023, reflect strong sectors such as palm oil and minerals. Still, improvements in electronics and higher-value manufacturing remain inconsistent and depend heavily on policy choices. This mix indicates some reallocation but also areas where rerouting and regulatory workarounds explain export increases.

Thailand and Malaysia show how different industries matter. Thailand’s car industry, with local supply chains and foreign-owned factories, is a good example of reallocation. Making cars and parts creates steady jobs and helps suppliers. Malaysia’s electronics and semiconductor exports have grown a lot, but much of this is just one step in a global chain, often using mostly imported parts. When exports go up, but local content doesn’t, it’s more like rerouting. This helps logistics and service firm,s but doesn’t mean the whole industry is changing.

The Philippines and Singapore are at opposite ends of the spectrum. The Philippines has seen growth in electronics assembly and business process services. Whether higher-value manufacturing grows depends on strong supplier connections and better skills. Singapore, on the other hand, mainly acts as a high-value hub for logistics, finance, and complex re-exports. Most of its gains come from value-chain services, not from reallocation of low-value manufacturing. These differences matter because the social and financial benefits from reallocation are much greater than those from rerouting. Reallocation can expand the tax base and create payroll gains that support social spending. Rerouting, however, may bring narrow gains for companies, mostly in ports and trading firms. Policymakers should not assume that higher export numbers always mean real development.

Policy Responses and Practical Implications

When a country is seeing reallocation, the best policies are clear: invest in skills that fit new jobs, remove barriers to power, transport, and customs, and encourage suppliers to set up locally. Partnerships between government and business can link training to company needs, helping local workers move into better jobs. Fiscal policies matter too. Tax credits for investment and research can attract multinational projects and build longer supply chains. These steps may be expensive, but they pay off because reallocation brings lasting benefits.

If a country mainly serves as a rerouting hub, its policy priorities should shift. The focus should be on stronger customs checks, enforcing rules of origin, and increasing service exports to get more value from transit trade. This involves building up logistics, port services, and certification standards. Policymakers can encourage a shift from rerouting to reallocation by linking export approvals to clear local-content rules and using revenue from logistics to fund education and infrastructure. However, expecting rapid industrial growth from rerouting alone is unrealistic. Spending on finance and training should be targeted, since training is most effective where reallocation is already happening.

Trade policy tools are important. Preferential trade agreements and clear rules of origin can support reallocation by making domestic production more valuable in key markets. Weak rules or loopholes, on the other hand, encourage rerouting. When a major market imposes tariffs on certain goods from a specific country, companies may respond by performing minimal assembly or paperwork in another country, a common rerouting tactic. Spotting these patterns requires sharing customs data, improving input tracking, and using company surveys to estimate domestic content. International partners and donors can help by funding data systems that show whether growth is real or just statistical. The good news is that these methods are practical. Value-added accounting, input and output tracking, and surveys give policymakers the evidence they need to choose between more education spending and tighter customs enforcement.

It is vital to anticipate common criticisms. Some argue that rerouting still presents an opportunity, suggesting that transit trade builds management skills and leads to future reallocation. While this can be true, especially when logistics firms reinvest profits into local capacity, it is important to consider the alternative. Many countries have experienced transit booms that have left little lasting manufacturing in their wake. The best approach is to treat rerouting as a temporary state. Use the financial gains from logistics to fund strategic investments in education, standards, and supplier development, but avoid overcommitting to industrial subsidies unless there is clear proof of rising domestic value added.

Base Actions on Proof, Not Just Invoices

The main idea is that rising export invoices can obscure transit trade rather than real production, and this should change how we measure success. Policies based only on total export growth risk waste limited public funds. Instead, governments and donors should start with a careful diagnosis. Measure domestic value added, track supplier networks, and review company investment plans. Where reallocation is happening, invest more in training, infrastructure, and standards. Where rerouting is more common, focus on customs integrity, logistics efficiency, and turning transit revenue into development funding. In Southeast Asia, the situation is mixed. Real industry improvements exist alongside active rerouting. This variety is an opportunity, letting each country create a strategy that fits its strengths and aims to turn temporary transit into lasting growth. The key question is not just whether export shares went up, but whether they created real jobs, real suppliers, and real value. If not, the next step is clear: build the systems that turn rerouted flows into domestic growth and stop confusing invoices with real industrial progress.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

IMF. (2025). Demystifying trade patterns in a fragmenting world. IMF Working Paper.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2025). The great trade rearrangement. McKinsey & Company.

Viet Nam Export Data. (2025). Breaking down Vietnam's electronics exports. VietNamExportData (report).

VoxChina. (2025). Exports in Disguise: Trade Rerouting during the US-China … VoxChina.

WITS / World Bank. (2024). Indonesia Trade Summary 2023. World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS).

Comment