Beyond the Benchmark: Questioning the 10,000-Hour Rule for Elite Performance

Input

Modified

The 10,000-hour rule fits early skill, not true peak AI raises the floor; judgment and transfer win Teach breadth first, verify always, specialize later

Elite performance is best viewed as a process of growth, not just a number to hit. A 2025 study in Scientific American notes that many top adults weren’t always the best in their field when young. Often, great performance arrives later than expected. This fits what we’ve seen before in science, music, and sports, where people often do their best work in the middle of their careers, after years of work. The difference between good and great gets bigger as people age and learn. Yet the 10,000-hour rule remains an accepted idea for becoming good at something, leading schools and training programs to focus more on hours than on skill development. This isn’t as helpful now that AI can help people improve quickly and reach a decent level of skill that used to take a lot of time to achieve. Now, it’s more important to have skills that show up later, such as combining ideas, making good decisions, and adapting to change. The 10,000-hour rule doesn’t teach these skills, but practice does. To help people become truly great, teaching should focus on growing skills over time, not just racking up hours. The 10,000-hour rule should be just a starting point, not the final goal.

Rethinking the 10,000-Hour Rule in the Age of AI

The idea that putting in 10,000 hours of practice makes you an expert is easy to understand and sounds good. Studies of top violin players and stories about famous programmers and successful bands helped make this idea well known. But a 2014 research study that examined many related studies gives us a more detailed view. Practicing a lot does help, but how much it helps changes depending on what you’re doing, and it matters less at the highest levels. Practice is very important in fields like games and music, but it’s less important in jobs like medicine and law. This doesn’t mean practice is a waste of time. It means when and how you practice matters a lot. For those who want to be the best of the best, big steps forward usually happen later, after you have built a very strong base of skills.

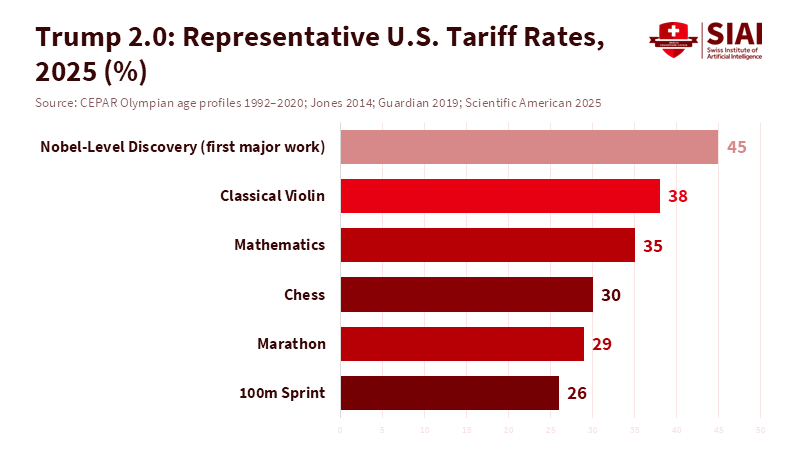

New reports from 2025 pull data from different fields to see when people usually reach their prime. The trend is seen that sports and chess players often peak in their 20s or early 30s, but musicians and scientists usually peak later, in their 30s and 40s. People who win Nobel Prizes often do their key work around middle age. Large datasets on athletes and Olympic teams show that ages have been trending up in recent decades. A 2019 study of top violinists found that players who were only good sometimes practiced more than the best players, which goes against the idea that more practice always makes you the best. In short, the 10,000-hour rule is just a general guide. It points to basic ability, but not to top-level success.

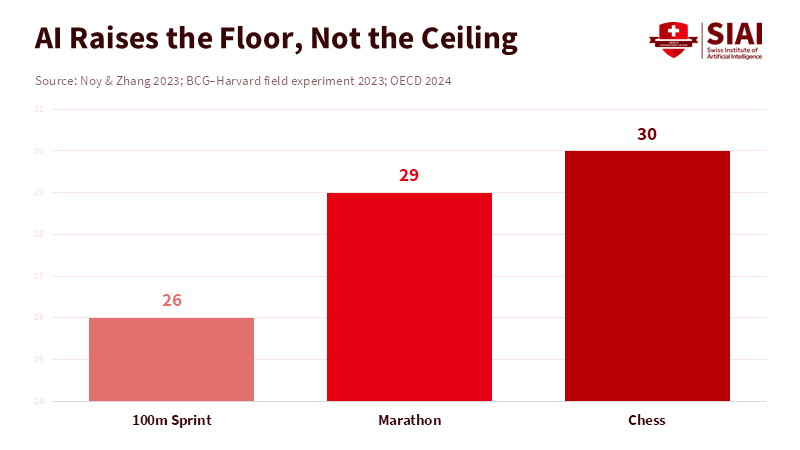

AI is speeding up the rate of initial improvement. Studies show that strong chatbots have made people faster and helped them do better work on writing and business tasks. Testing in business settings shows they are also helpful for work that follows a pattern, but their effectiveness declines when you need to think creatively. The message for teachers and leaders is simple. AI can make many students appear to have 5,000-hour skills for regular tasks. This raises the standard and pulls everyone closer together in the middle, but it doesn’t raise the bar at the very top. It actually makes skills like putting ideas together, coming up with new ideas, using what you know in different ways, and making smart decisions even more needed. The 10,000-hour rule can’t explain what’s happening now. Programs based on it will struggle.

The Late-Blooming Curve: From “Top” to “Top-of-Top” in Education

The best students and trainees get good grades right away. They read fast, write clearly, and do well when they perform. The top-of-the-top keep getting better, too. They try new ways of doing things. They use different tools and ideas together. They deal with hard problems that don’t follow the rules. This later-life growth can be seen across many fields. Studies show that people in scientific fields produce more work after they finish their training, and that this output peaks in the middle of their careers. In sports, data shows that the ages at which people perform best in the Olympics have remained the same or even increased. Studies also warn that being good early can trick those responsible for selecting talent. These facts show that it’s important to value growth over time.

Education still focuses on early success. We reward people for focusing on one thing when they’re young, and we spend too much time tracking hours in one subject. We call kids who are good at something early future stars. But data from 2025 shows that focusing on one thing early often means you’re less likely to be great later. Having many kinds of experiences when you’re young predicts that you’ll be more skilled as an adult. Music, science, chess, and sports all show that new learning later in life is seen as a good step. Education should keep this in mind. When schools rush to reach 10,000 hours quickly, they might produce strong top performers who stop improving later. When they plan for growth over time by waiting to focus on one thing, training across subjects, and creating spaced-out challenges, they make it more likely that some people will become top-of-the-top.

The rise of AI has heightened the demand for educational outcomes. AI can now write, fix computer code, summarize information, and translate at a pro level. Experiments at MIT have shown significant gains in both speed and writing quality when performing standard writing tasks. Studies led by Harvard that involved consultants have shown that AI has perks and downsides: It excels at tasks similar to the data it was trained on, but it struggles when you need to be creative. For schools, the facts speak for themselves. Only focusing on hours for basic skills will cause graduates to compete with machines. Training that focuses on advanced skills—such as framing problems, thinking about cause and effect, integrating ideas from different fields, and checking data under pressure—will help grads outperform AI.

Designing for the Long Arc of the 10,000-Hour Rule

Policy should see the 10,000-hour rule as a starting point, not the main way to think about training. First, we have to raise what we mean by good performance, at least compared to what AI can do. If AI can do what 5,000 hours of normal, repetitive work can do, then good should mean work that uses background knowledge, checks sources, and can be applied across many fields. This idea should inform how we test students. Big projects should require students to change models and check information to go beyond what AI can normally do. Grading for writing should focus on statements that can be checked and thinking in a reasonable and logical manner, along with how smoothly someone writes. Coding classes should test students with difficult tests and real-world problems, not just by having them find the right answers to simple problems.

Second, be patient. Data on when people peak and when they learn things later in life support waiting to focus on one specific thing. College programs should make their classes more varied in the first two years. Teacher training should include experience across different grades, teaching styles, and subjects. Rules for distributing school funds can favor projects that involve many subjects and take place at times when things change. In music and sports, this might mean trying different instruments or sports before choosing one. In science fields, it might mean adding statistics to what you know and learning how to communicate. The goal should be to build a solid foundation of knowledge that helps when it’s time to really learn something well.

Third, we need to check what we learn and say as part of basic skills. AI makes it easier to write and speak smoothly, but it also makes it easier to make mistakes. Studies show that using AI without watching it can increase the number of mistakes people make confidently. Schools should teach how to check information and grade students on it. Students should write down how they checked their work when they turn in papers. Students who identify problems with models and provide counterexamples should be rewarded. Assignments can push students to use many models for the same problem and figure out why they don’t match. This kind of training helps people build habits they can’t develop just by putting in hours.

Fourth, we need to rethink how we pick people for training. We should look at how much people can grow, not just at what they’ve already done. Sports are starting to adjust based on age relative to peers, and education can do the same by looking at what people have done over time. Policy should focus less on how people perform on a single test and more on projects that unfold over time and allow for change. We should invest more in programs that support people in the middle of their careers and recognize those who make comebacks. Teacher career paths should reward late-career great breakthroughs. Relying on the 10,000-hour rule to choose people risks missing those who do well when it matters most.

Finally, we should give credit to the late curve. Pay, promotions, and how we measure performance should focus on using what you know in new ways and generating new ideas. Universities can value articles that share ideas from many fields. Schools can celebrate fixing real issues, not just getting high test scores. Regions can track growth and work through problems, not just getting things right the first time. Institutions should reward work that can’t be done by AI.

What the evidence means for classrooms, campuses, and education offices

For teachers, the change is from counting hours to planning long-term growth. Keep practicing hard. Grade and train on tasks that require changing models, using multiple sources, and using what you know in different areas. Create projects where AI can be used to produce initial versions, but students must deliver checked, testable results. Make routines that show learners where a model stops being useful, and teach them how to recover. That’s how we build good judgment, which the best people use when tools stop working.

Policymakers should change national education plans to reflect the new state of education. While many countries are planning to introduce AI in schools, these plans must go beyond mere technology use. We need standards for checking information, documenting work, and learning across different fields. We need long-term research funding to track people through late-stage growth and determine when they peak across different subjects. Scholarship programs should focus on breadth before specialization and give chances to those who bloom later. Accountability systems have to measure unique results and check reasoning, not just volume.

Stop the stopwatch; fund the arc

We shouldn’t fight the 10,000-hour rule. We should move past it. The strongest data from 2023 to 2025 says that practice matters, but becoming the very best takes longer, happens later, and isn’t as expected as a simple number suggests. It also shows that AI has changed the game. Tools that quickly and cheaply improve average performance. But they don’t create unique ideas, the ability to use what you know in different areas, or good judgment on demand. These skills come later. Education that wants to rise above the level of tools has to invest in breadth first, secure learning later, and make checking information a normal part of the process. That’s how we tell human work apart in a world where machines can do many things pretty well. That’s how we stop early stars from disappearing and help careers shine when it matters.

Schools should shift from the stopwatch model to a map metaphor, giving learners time to explore, fail, and change direction. Tests should reward mixing ideas and claims that have been tested. Funding should support chances to change direction and get second chances. AI should be used to speed up early learning, while education should plan for needs that technology can’t predict. By using these plans, schools can keep the most useful part of the 10,000-hour story—respect for effort—while giving a more correct idea of what excellence is. The best people succeed not by just putting in hours, but by using their time smartly.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BCG & academic collaborators (2023). Navigating the jagged technological frontier: Field experimental evidence. Harvard Business School Working Paper / BCG report summary.

Guardian. (2019, Aug. 21). Blow to 10,000-hour rule as study finds practice doesn’t always make perfect.

Jones, B. F. (2014). Age and scientific genius. NBER Working Paper 19866.

Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychological Science.

MIT (Noy, S., & Zhang, W.). (2023). Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative AI. Published summary in Science (2023).

OECD. (2024). The impact of artificial intelligence on productivity, distribution, and growth.

Scientific American. (2025, Dec. 18). Here’s how much practice you need to become the best in the world.

University and Olympic datasets (2021). Peak performance age in sport: Age distribution of Olympians, 1992–2020. CEPAR Fact Sheet.

Wang, T., et al. (2024). Early excellence and future performance advantage. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.

The Kid Should See This (2025, Nov. 4). Beyond 10,000 hours: what’s the best way to get good at a skill? (featuring David Epstein’s argument for sampling before specialization).

Wall Street Journal. (2025, Dec. 18). Most top-achieving adults weren’t elite specialists in childhood (reporting on a Science study).

Comment