The Quiet Constraint: Why China’s Domestic Priorities Limit Global Ambitions

Input

Modified

China’s global strategy is increasingly shaped by domestic economic pressures rather than imperial ambition Youth unemployment and slowing growth are pushing policy inward and favoring stability over expansion Education and skills systems now sit at the center of long-term power

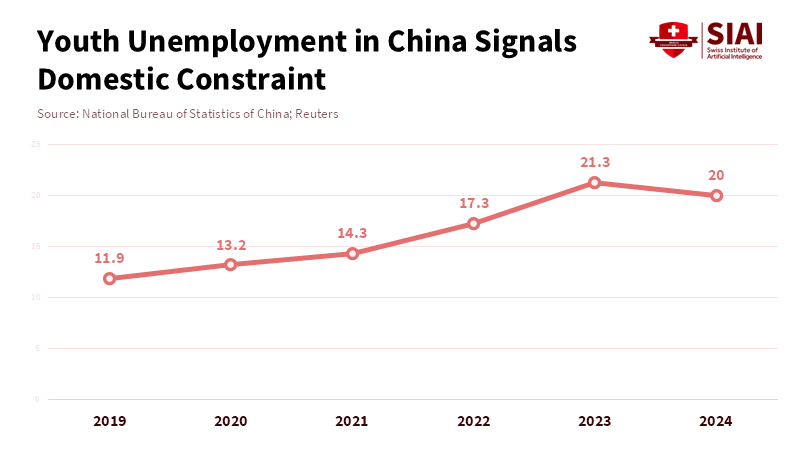

China's internal considerations, while seemingly less attention-grabbing than discussions of superpower competition, are, in reality, essential for understanding its global approach. The starkest indicator of this is the record 21.3% jobless rate among urban residents aged 16–24 in mid-2023. Such extensive youth joblessness presents difficulties for broad, expansive foreign policy initiatives. Instead, it redirects political focus inward, emphasizing job creation, housing, public order, and economic growth. China is managing a massive economy, dealing with a downturn in the property sector (with developer investment decreasing by approximately 10% in 2024), and facing a demographic plateau that shifted into decline in 2024. These challenges are not excuses, but they do shape the country's choices. They reveal how state strategy prioritizes economic strengthening, social stability, and specific technological improvement, as opposed to a large-scale global expansionist project. For education authorities and decision-makers, the shape of China’s external ambitions is being determined domestically – within schools, job markets, and local government offices.

Understanding the domestic factors guiding China’s strategy

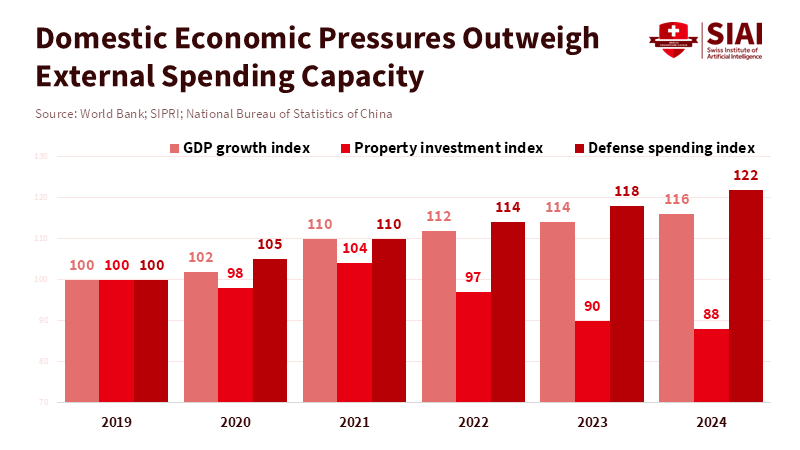

The logic is clear: When youth unemployment is high, the property market is slowing, and the population is ageing, this pushes political risk towards domestic solutions. If more than 20% of young urban residents struggle to find jobs, national ambitions are refocused. While China can allocate funds to defense and projecting power, as it did with consecutive increases in military spending, there are limits. Funds and skilled workers dedicated to public order and economic recovery are not available for extensive power projection.

This trade-off is apparent in policy decisions that strengthen job programs, vocational training, and efforts to boost consumption, before supporting major new activities abroad. The private sector matters, but government policy is increasingly steering capital toward sectors that generate employment and infrastructure projects that quickly offer jobs, not toward risky global projects.

This shift affects strategic funding and staffing. Government research priorities now typically favor advancements in industrial technology and semiconductor development over large diplomatic operations. Local administrations, heavily reliant on property revenue, are focused on reallocating land and financial resources to protect jobs and their tax base. Central government directives mirror this shift: targets for economic growth and language centered on the people are genuine indicators. Education leaders and university administrators will see that the state rewards programs that swiftly create marketable skills, apprenticeships, and training opportunities. International collaborations that lack a clear domestic benefit will be subject to closer examination. The external symbols of power, such as ports, initiatives, and Belt and Road forums, may still be present, but the driving force behind these actions will require apparent domestic advantages.

Domestic priorities also influence China's narratives and legitimacy. The Party’s agreement with the people has changed: economic performance and stability are now more important than promises of steadily rising living standards. This change increases the political cost of foreign risky initiatives. Every resource spent to exert influence abroad must be justified by the resulting advantages at home. State communications connect international projects to job creation, supply-chain security, technology transfer, or access to markets. Education policy follows this direction, emphasizing job-related skills, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) with practical application, and skills useful for growing domestic sectors. This is not inaction but a strategic adjustment. It suggests that China’s global behavior in the next five to ten years will be measured, practical, and gradual rather than imperialistic.

How economic constraints reshape statecraft

Economic realities are crucial for strategy. While China's GDP remains large globally, growth has slowed, and the composition of this growth has changed. Real estate, previously a major contributor, no longer serves as a dependable stabilizer. Investment in property development decreased by about 10.6% in 2024, and the number of unsold properties and weak housing sales have strained local government finances. These restrictions directly translate into diplomatic and defense decisions: tax shortfalls reduce the ability to fund projects abroad and support great public diplomacy efforts. Thus, central planners prefer focused, low-risk investments abroad and concentrate on stabilizing domestic demand through consumption and infrastructure that quickly generate employment.

Additionally, financial considerations shape institutional policy in education. Universities and vocational institutions are pushed to align with sectors that can employ graduates on a large scale. This shift leads to a reallocation of talent, with more students directed toward applied engineering, health services, software maintenance for domestic applications, and specialized manufacturing. Long-term research continues, but funding is prioritized for speedier results. This is highly relevant to how China competes globally. If sophisticated, basic science driven by curiosity is given lower priority than technological catch-up, international leadership in pioneering fields may be delayed or pursued through partnerships rather than achieved through individual Chinese dominance. For decision-makers in other countries, this creates a consistent trend: China will aim to secure supply chains and standards through practical agreements and targeted investments rather than through open-ended geopolitical ambitions.

This financial tightening also results in changes in migration and engagement with the diaspora. Given a weaker job market, efforts to send students abroad and gain skills from other countries are shifting toward programs to retain talent domestically. Scholarships, incentives to return home, and doctoral programs linked with industry encourage graduates to stay in China. This creates a flow of human capital inward that supports domestic changes but reduces the immediate motivation to project power by sending elites abroad. The result is strategic patience, an emphasis on strengthening the domestic base so that if opportunities to lead globally emerge later, the state will be in a better position to take advantage of them.

What educators and policymakers must do

Given that China’s short-term strategy is limited by domestic priorities, the world’s educators must adapt. First, curricula must be modified to reflect labor market conditions. That means expanding vocational routes, micro-credentials aligned with specific industries, and more robust local industry partnerships that lead to defined job prospects. Such changes will reduce mismatch for graduates and lessen political pressure by turning education into employment. Second, administrators must build resilience into international exchanges. Partnerships should focus on two-way learning that achieves domestic aims: shared applied research, industry-supported internships, and exchange of technology that assists local companies in advancement. Programs that are based solely on prestige risk losing funding and political support whenever budgets tighten.

Policymakers outside China should also reconsider their approaches. If Beijing’s resources are directed inward, this creates both potential risks and opportunities. The risk is that concentrated investment, whether in core technologies or strategic ports, will remain aggressive. The opportunity is that broad, costly expansionist actions are less likely in the short term. This creates opportunities for multilateral cooperation on trade regulation, greater openness in supply chains, and educational exchanges focused on shared workforce needs. Institutions in the West can respond by strengthening practical cooperation to improve skills, facilitating teacher exchanges, and conducting research that tackles shared industrial challenges. This approach reduces confrontation and preserves paths for influence grounded in shared economic gains.

Finally, education leaders in all systems must prepare for change. If demographic changes and pressure related to youth job prospects pose a political risk, abrupt policy shifts are likely. Programs must be adaptable and scalable. Governments should maintain funds for rapid retraining and mental-health support, since political stability relies as much on public cohesion as on employment numbers. In summary, adapting education to the reality of China’s domestic priorities is both important for national security and good strategy, as it protects young people and stabilizes economies, reducing the likelihood of ill-considered foreign policy choices that could lead to conflict.

Returning to the initial point, the record youth joblessness in 2023 is a warning sign that directs policy internally and narrows the scope of ambition. China still possesses vast resources and real potential for international leadership. But as a result of domestically driven limits, in the next five to ten years, Beijing will more often choose consolidation over expansion, jobs over grand gestures, and resilience over risky overreach. For educators, administrators, and policymakers, this reality implies a simple piece of advice: align skills with the economy’s immediate needs, form practical partnerships, and build institutions that can weather storms. This is how we lower political tensions and allow for cooperation. If the global community seeks a stable China that raises living standards at home without energetic rivalry abroad, it must ground its policies in practical efforts on skills, jobs, and shared economic resilience. The politics of power begin in the classroom and in the job market, and the choices we make here will determine whether competition becomes containment or true collaboration.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

International Monetary Fund. (2025). People’s Republic of China: Country Data and Reports. IMF.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2025). Press Releases and Statistical Communiqués on 2023–2024 Economic Performance. NBS.

Pew Research Center. (2024). Views of China and Xi Jinping in 35 countries. Pew Research Center.

Reuters. (2024). China's new home prices decline at fastest pace since 2015. Reuters.

SIPRI. (2025). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Trading Economics. (2024). China: GDP and Population Data Series. Trading Economics.

World Bank. (2024). China Country Data: GDP and Development Indicators. World Bank.

Comment