Geopolitical Risk and Corporate Borrowing: Why Uncertainty Now Shapes Investment More Than Interest Rates

Input

Modified

Geopolitical risk now restrains corporate borrowing more than interest rates Asian firms delay investment when trade and policy rules become unpredictable Stable policy signals matter more than cheaper credit for reviving investment

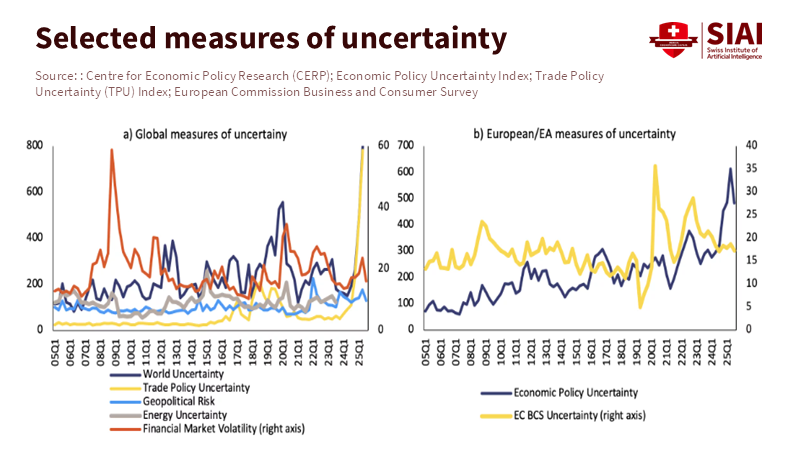

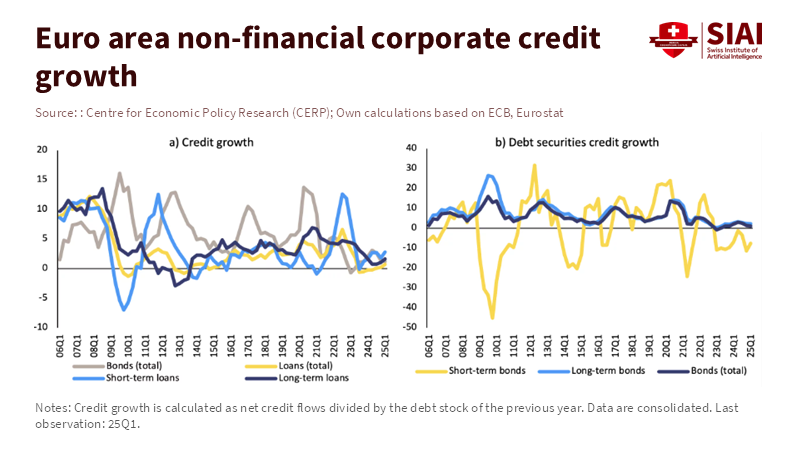

In 2024, global interest rates started to level out, but companies did not increase borrowing as expected. Even with credit available, many firms held back. The main reason is not borrowing costs, but geopolitical risk. Surveys from central banks and international organizations between 2023 and 2025 show that companies now see geopolitical tensions, trade barriers, and unpredictable policies as bigger threats to investment than inflation or tighter monetary policy. This marks a shift from past cycles, when lower rates eventually led to more borrowing after downturns. Today, uncertainty is the main barrier. The issue is not a lack of capital, but that companies cannot predict what will happen next. Tariffs can return quickly. Export rules may change overnight. Supply chains can break down without warning. Companies need steady cash flows to borrow with confidence. If they cannot predict revenue beyond the near future, they avoid taking loans, regardless of interest rates. This shift matters for education systems, policymakers, and administrators because investment slowdowns now come from uncertainty, not just financial problems. Ignoring this change could lead to poor decisions and ineffective policies.

Reframing Corporate Borrowing in an Era of Geopolitical Risk

Many existing policies continue to assume that corporate borrowing is primarily influenced by credit conditions. This perspective anticipates that firms will respond predictably to changes in interest rates, liquidity, and financial health. However, this assumption is increasingly outdated. Geopolitical risk has fundamentally altered corporate decision-making. Borrowing now represents a significant and potentially irreversible commitment in an environment characterized by pervasive uncertainty. Unlike previous risks, which could often be managed or diversified, geopolitical risk simultaneously affects regulatory frameworks, market access, logistics, and currency stability, making it difficult to mitigate. Recent studies demonstrate that even firms with sufficient internal resources are more likely to postpone investments. This represents a marked shift from earlier periods, when access to credit was the primary determinant. Borrowing is now perceived as discretionary rather than essential. This evolving perspective underscores the limitations of traditional policy tools focused solely on easing credit, as such measures are ineffective unless uncertainty is directly addressed.

Evidence from both advanced and emerging economies reveals a consistent pattern. Surveys by major central banks from 2023 to 2025 indicate that firms frequently cite geopolitical developments and shifts in trade policy as primary reasons for deferring capital expenditures. Although lending standards may be relaxed, demand for loans remains subdued. Notably, this trend is not solely attributable to pessimism, as many firms continue to report stable or robust current demand. The core issue concerns planning horizons: when access to markets or regulatory alignment can change abruptly, long-term projects become inherently risky, even if short-term sales are strong. As a result, corporate borrowing is increasingly disconnected from traditional macroeconomic indicators.

Looking at the issue this way also reveals a major policy gap. Financial regulators focus on keeping banks strong, while trade and foreign policy officials work separately. But companies see these risks as connected. When geopolitical risk rises, borrowing declines even in the absence of a financial crisis. Treating this only as a credit problem misses how important clear and reliable policies are.

Why Asia Reveals the New Borrowing Divide

Asia shows clearly how geopolitical risk affects corporate borrowing, with big differences between countries. Some nations, especially those less dependent on fragile global supply chains, have adapted by building new trade partnerships and boosting domestic demand. In contrast, countries deeply involved in pressured supply chains face more uncertainty. For example, reports from international financial organizations say that firms in parts of Southeast Asia and South Asia continue to invest by shifting exports and expanding regional trade, while firms in economies hit by new tariffs and technology limits are more likely to delay borrowing and pause projects.

The key contrast in Asia is not simply between economic growth and stagnation, but between environments that offer predictability and those fraught with uncertainty. In countries where government policies are seen as stable—such as parts of Vietnam and Indonesia—firms continue to borrow, though cautiously. In countries facing more unpredictable geopolitical developments, borrowing behavior becomes increasingly conservative, with a preference for cash reserves rather than expansion. This varying pattern is visible across the region's manufacturing, energy, and technology sectors. Firms delay borrowing less because of the quality of investment opportunities, and more due to the challenge of anticipating future policy or trade conditions. Corporate borrowing behavior in Asia is directly linked to how predictable and stable companies perceive their policy environment.

Importantly, this pattern challenges the assumption that developing economies are uniformly more vulnerable. Some emerging Asian economies mitigate risk through flexibility and regional integration. Others suffer precisely because of their success in global specialization. The lesson is that exposure, not income level, determines borrowing behavior under geopolitical stress. For policymakers, this suggests that stability and clarity matter as much as financial support. For educators and administrators, it signals that workforce planning and institutional investment will increasingly depend on geopolitical literacy rather than on economic forecasting alone.

From Interest Rates to Irreversibility: How Firms Decide Not to Borrow

Corporate borrowing choices are shaped by the belief that once money is invested, it cannot be easily retrieved. With higher geopolitical risk, this becomes even more dangerous. Companies have to consider the possibility that tariffs, sanctions, or new rules could reduce their returns after they invest. This explains why borrowing stays low even when financial conditions improve, and why many sectors are holding more cash even though they still need to invest.

Research conducted by international organizations between 2023 and 2025 demonstrates that uncertainty has a greater dampening effect on investment than elevated borrowing costs. As a result, uncertainty serves as a more compelling reason for firms to postpone action. Rather than reducing investment outright, companies tend to delay their plans, leading to deferred borrowing rather than cessation. These cumulative delays ultimately hinder productivity and skill development. Education systems are affected when firms reduce training budgets and decrease collaboration with academic institutions.

Some say companies will eventually adjust and resume borrowing. While adaptation does happen, it is slow and uneven. Changing supply chains, finding new markets, or redesigning products all need a certain level of confidence. Without clear and reliable policies, even adaptation becomes risky. This is why geopolitical risk has a longer-lasting effect than financial ups and downs. Interest rates can change, but rules set the boundaries. If rules are unstable, companies stop borrowing, no matter the cost.

Policy Implications for Educators, Administrators, and Governments

Policy responses need to start by recognizing the problem. Today, uncertainty—not a lack of money—holds back corporate borrowing. Governments cannot fix geopolitical risk just by offering cheap credit. What companies need is a credible commitment. Clear trade policies, predictable regulatory timelines, and coordination among ministries help reduce uncertainty, even as tensions persist. Stability does not mean everyone agrees, but it does mean having clear rules.

For education policymakers, the implications are indirect but serious. Investment delays reduce demand for skilled labor growth and weaken partnerships between firms and institutions. Universities and vocational systems must anticipate more volatile funding cycles and diversify engagement beyond single industries or markets. Teaching geopolitical risk assessment is no longer optional. It is a core economic skill.

Administrators face similar challenges. Capital projects linked to industry collaboration may stall unpredictably. Planning must account for delayed private investment and shifting employer demand. Governments can support this transition by aligning education, trade, and industrial strategies rather than treating them separately.

The central lesson is simple. In a world shaped by geopolitical risk and corporate borrowing decisions, predictability is the most valuable policy asset. Without it, investment will remain cautious, growth will slow quietly, and skills formation will lag. Restoring borrowing requires not just lower rates, but firmer rules.

Restoring Confidence Without Illusion

Companies' reluctance to borrow, even when financial conditions are stable, suggests a larger change is underway. Geopolitical risk has changed how companies think about investing. If they cannot predict market access, rules, or supply chain stability, borrowing feels more like a risk than an opportunity. This explains why old stimulus methods are less effective and why investment recoveries seem weak.

To return to the main point, the real issue is not the cost of borrowing, but confidence in the future. Companies need to be able to plan ahead with some certainty. Policymakers cannot eliminate all geopolitical risks, but they can clarify them. Clear rules, reliable commitments, and coordinated policies help companies look ahead, even in tough times. For educators and administrators, the challenge is to adjust their institutions to this new reality. Investment cycles will be harder to predict, and skill needs will change more quickly. Understanding geopolitics is now as important as understanding economics. Ignoring this shift means preparing students and systems for a world that no longer exists. This is a call to action based on careful analysis, not fear. We need to stabilize expectations, not just financial markets. Only then will companies start borrowing again and drive sustainable investment.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

International Monetary Fund. Global Financial Stability Reports and regional outlooks, 2023–2025.

International Monetary Fund. Asia and Pacific Department analytical blogs, 2024–2025.

Reuters. “Policy uncertainty, geopolitical risk top stability concerns, Fed surveys,” 2023–2025.

Bank for International Settlements. Annual Economic Reports, 2023–2024.

European Central Bank. Corporate borrowing and investment survey summaries, 2023–2024.

Comment