When Sanctions Stop Signaling: North Korea Normalization and the Quiet Collapse of Nuclear Deterrence

Input

Modified

Sanctions are no longer fully isolating North Korea as its nuclear program advances This normalization weakens global non-proliferation norms The shift raises nuclear pressure on U.S. allies like South Korea

In 2024, the global sanctions regime against North Korea crossed an inflection point that was easy to miss but hard to reverse. Despite remaining under some of the most comprehensive international restrictions ever imposed, Pyongyang expanded its strategic room for maneuver rather than contracting it. The reason was not internal reform, diplomatic outreach, or renewed talks with Washington. It was structural. Russia, under pressure from its prolonged war in Ukraine, deepened its political and military cooperation with North Korea, while China adjusted its posture in response to growing competition with Moscow and rising tensions with the United States. The result was not formal recognition, but something more destabilizing: the visible erosion of isolation. For the first time since the early 2000s, North Korea demonstrated that it could retain a growing nuclear arsenal without suffering escalating external punishment. That outcome matters far beyond the Korean Peninsula. It weakens the signaling power of sanctions as a non-proliferation tool and alters how other states, watching closely, assess nuclear ambition.

North Korea normalization and the changing mechanics of isolation

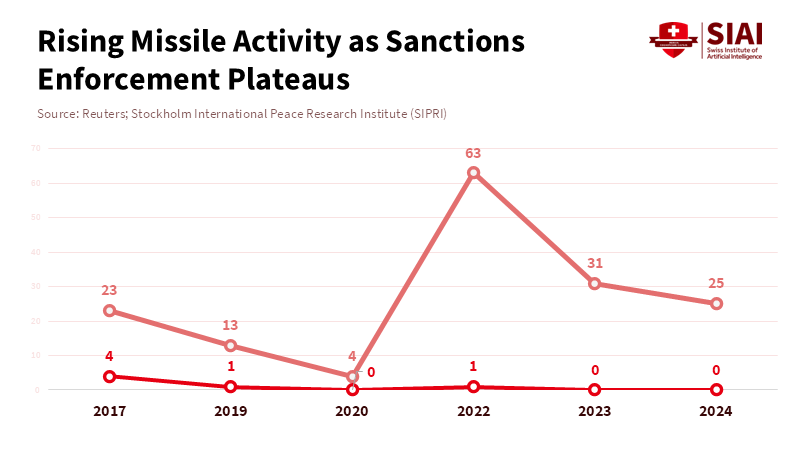

For decades, international strategy toward North Korea rested on a single assumption: that nuclear advancement would deepen isolation, raise economic costs, and eventually force compromise. That logic held imperfectly but consistently. Even when sanctions failed to halt weapons development, they constrained trade, access to technology, and diplomatic legitimacy. What changed after 2023 was not the sanctions legal framework but the geopolitical environment in which they operated.

Russia’s growing reliance on alternative partners after its invasion of Ukraine created incentives that ran directly against sanctions enforcement. By late 2024, Moscow and Pyongyang had formalized their relationship through a ratified strategic partnership treaty, accompanied by public commitments to expanded cooperation. Reporting from multiple international outlets confirmed exchanges involving arms supplies, technical assistance, and labor support. While some claims — particularly regarding combat troop deployments — remain disputed or only partially substantiated, the broader pattern is clear: Russia has treated North Korea less as a pariah and more as a strategic asset.

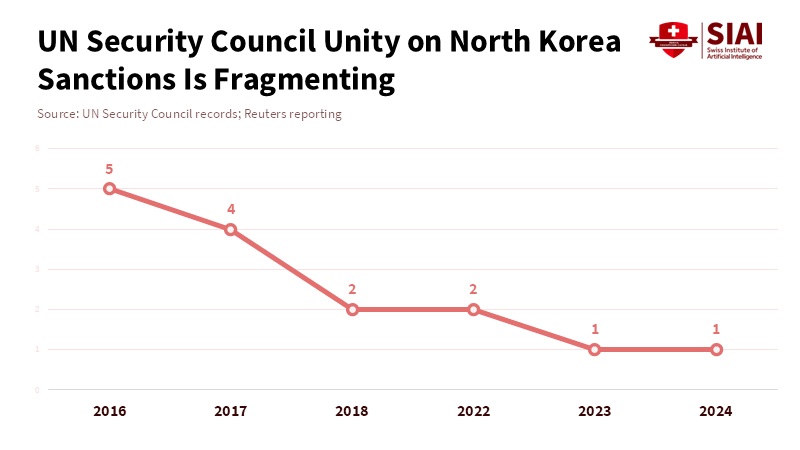

China’s response has been more cautious but equally consequential. Beijing has not openly endorsed Pyongyang’s nuclear status, nor has it abandoned support for denuclearization in principle. Yet enforcement behavior matters more than rhetoric. Border trade, energy flows, and diplomatic shielding at multilateral forums have continued with limited disruption. At the same time, China’s growing rivalry with Russia has reduced its willingness to align fully with Moscow’s North Korea policy, producing a fragmented enforcement environment rather than a unified front.

This fragmentation is critical. Sanctions are most effective when they are universal, predictable, and costly to evade. Once major powers selectively comply or reinterpret obligations, sanctions lose their deterrent clarity. North Korea has not been formally normalized. But functionally, it has demonstrated that nuclear possession no longer guarantees deepening isolation. That distinction — between legal status and lived reality — is the hinge on which future proliferation decisions will turn.

Why North Korea's normalization reshapes nuclear incentives globally

Nuclear proliferation has never been driven solely by ideology or prestige. It is a strategic calculation rooted in cost-benefit analysis. States assess whether nuclear capability increases security, bargaining power, and regime survival, and whether the external costs are tolerable. When those costs appear manageable, restraint weakens.

The significance of North Korea's normalization lies precisely here. If Pyongyang can expand its nuclear arsenal, deepen ties with at least one major power, and avoid further material deterioration, then the traditional deterrent model breaks down. The lesson for other states is not that sanctions disappear, but that they can be absorbed, mitigated, or offset.

Iran is the most obvious observer. Tehran already operates near nuclear threshold status and has extensive experience navigating sanctions. The North Korean case strengthens the argument within Iran that nuclear capability, once achieved, may eventually be tolerated rather than reversed. Pakistan, while already nuclear-armed, provides another reference point: its experience suggests that strategic necessity can override proliferation norms. For smaller or less aligned states, the signal is more subtle but no less important. Nuclear ambition no longer looks like a one-way path to permanent exclusion.

This does not mean an immediate wave of proliferation. Technical barriers remain high, and political risks are real. But it does mean that the normative stigma attached to nuclear weapons is weakening. Non-proliferation regimes rely on credibility as much as enforcement. Once states begin to believe that nuclear possession can coexist with partial normalization, the threshold for restraint rises sharply. Crucially, this shift does not require formal recognition of nuclear status. It only requires evidence that possession is survivable. North Korea is now providing that evidence in real time.

Implications for education systems and policy training

The consequences of this shift extend beyond diplomacy and defense ministries. Education systems, particularly those that train future policymakers, analysts, and administrators, are operating under outdated assumptions about how non-proliferation works. Many curricula still frame nuclear restraint as the natural outcome of legal regimes, moral norms, and economic pressure. Those frameworks remain important, but they no longer explain observed behavior.

If North Korea normalization continues, students must be taught to analyze proliferation as a systems problem rather than a rules-based one. That means understanding how sanctions evasion networks function, how great-power competition distorts enforcement, and how informal legitimacy can emerge without formal legal acceptance. These are not abstract concepts. They shape real decisions made by governments under pressure.

Administrators should treat this as a strategic update rather than a thematic addition. Programs in international relations, security studies, economics, and public policy should integrate case-based learning focused on partial normalization scenarios. How does deterrence function when sanctions persist but lose signaling power? How do alliances adapt when the credibility of extended deterrence comes into question? What happens when legal norms and political realities diverge for extended periods?

For educators, the task is not to abandon normative teaching but to contextualize it. Students must be able to reconcile treaty texts with empirical outcomes. They must learn to ask not only what the rules say, but how they are applied, circumvented, or selectively enforced. Integrate real-world scenario analysis into curricula and prioritize the development of adaptive policy skills. Begin updating course frameworks and policymaker training now, ensuring future leaders are equipped to navigate this evolving security environment.

South Korea, alliance strain, and the nuclear question

No country is more exposed to the implications of North Korea's normalization than South Korea. Seoul has long accepted reliance on U.S. extended deterrence as the price of non-nuclear status. That bargain rests on two assumptions: that North Korea’s nuclear program would remain constrained by isolation, and that U.S. security guarantees would remain unequivocal.

Both assumptions are now under strain. If North Korea retains and improves its nuclear arsenal while expanding external partnerships, the security environment facing South Korea deteriorates in qualitative terms. This does not automatically produce a South Korean nuclear program. Domestic opposition, alliance commitments, and international law remain powerful constraints. But the political conversation has already shifted.

Public opinion polling and elite debate in South Korea increasingly reflect concern about the credibility of deterrence. Calls for nuclear sharing arrangements, redeployment of U.S. strategic assets, or even indigenous nuclear capability have entered mainstream discourse. These discussions are not policy decisions, but they signal pressure within the alliance. If North Korea's normalization proceeds without additional costs, those pressures will intensify.

For policymakers and educators alike, the key point is conditionality. South Korea’s nuclear debate is not driven by ideology but by perceived necessity. The more survivable North Korea’s nuclear status appears, the harder it becomes to argue that restraint is rational indefinitely. This dynamic underscores why normalization effects matter even when formal recognition is absent.

Addressing the counterarguments

Two objections dominate critiques of this analysis. The first is that North Korea remains economically weak and diplomatically constrained, making normalization an overstatement. The second is that sanctions can always be tightened if cooperation deepens too far.

Both arguments contain truth but miss the core issue. Economic weakness does not negate strategic success. North Korea does not need prosperity to alter proliferation incentives; it only needs survivability. The evidence suggests that survivability has improved relative to previous decades. Sanctions have not disappeared, but their marginal impact has diminished.

As for tightening enforcement, the problem is not legal authority but political coordination. Sanctions depend on the consensus of the major powers. That consensus has fractured. The United States can impose secondary sanctions, but doing so at scale risks broader economic and diplomatic consequences. Enforcement thus becomes selective, contested, and uneven. The implication is not fatalism. It is an adaptation. Non-proliferation strategy must shift from assuming isolation to managing partial integration. That requires new tools: targeted engagement, credible security guarantees, and economic incentives designed to compete with nuclear prestige rather than merely punish it.

Teaching for a world where signals matter less

North Korea normalization, even in its partial and informal form, marks a turning point in how nuclear deterrence and non-proliferation function. The lesson being transmitted is quiet but powerful: nuclear weapons, once acquired, may no longer guarantee isolation severe enough to force reversal. That lesson will shape decisions far beyond Pyongyang.

For educators, administrators, and policymakers, the response cannot be denial or nostalgia for a more coherent enforcement era. It must be preparation. Teaching must reflect reality, not aspiration. Policy training must incorporate ambiguity, competition, and imperfect compliance. And alliance management must confront the uncomfortable truth that credibility is no longer assumed.

The future of non-proliferation will be decided less by what treaties promise than by what cases demonstrate. North Korea is becoming such a case. Whether it becomes the model others follow depends on how quickly institutions adapt — and whether the international community can restore consequences before normalization hardens into precedent.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ABC News. (2025). North Korea calls nuclear weapons status irreversible amid U.S. pressure.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2025). North Korea, nuclear weapons, and the limits of denuclearization policy.

Reuters. (2024). Russia and North Korea ratify strategic partnership treaty.

Reuters. (2024). U.S. and allies warn of North Korea-Russia arms cooperation.

Reuters. (2025). China balances ties with North Korea amid great power competition.

Comment