When Markets Price What Models Cannot See

Input

Modified

Markets price geopolitical risk long before models can measure it Local-language news captures early signals that global indices miss LLMs can structure these signals, if used with care and oversight

After Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Russia's five-year CDS surged beyond 900 basis points, rising further as the crisis deepened. This showed that markets factor in unmeasured risk when conventional models fall short: prices reflect consensus on both quantifiable and uncertain risks. The central argument is that relying mainly on English-language media or broad indices can create a significant blind spot by missing the unique, valuable insights from local-language news and contexts regarding how citizens, businesses, and officials perceive threats. This analysis shows that building reliable measures of geopolitical risk from local news is critical. Institutions should incorporate these measures into their risk management processes, ensuring transparency in methods and robust governance. By doing so, educators, regulators, and market institutions can better align market prices with real-world risks.

Local news geopolitical risk offers another way to view unmeasured risk

The main argument of this approach is that to better assess financial risk, we must move away from general criticism of financial models and instead use language and local media as primary measurement tools. Rather than seeking a universal index of geopolitical risk, it is more effective to identify specific risks that affect different economic groups and note where they first surface. Local news sources are valuable here—they spotlight domestic tensions, cover local policy dynamics, and give regional context to external threats. This matters because domestic perceptions, alongside international events, significantly shape credit risk, investment strategies, and public budgets.

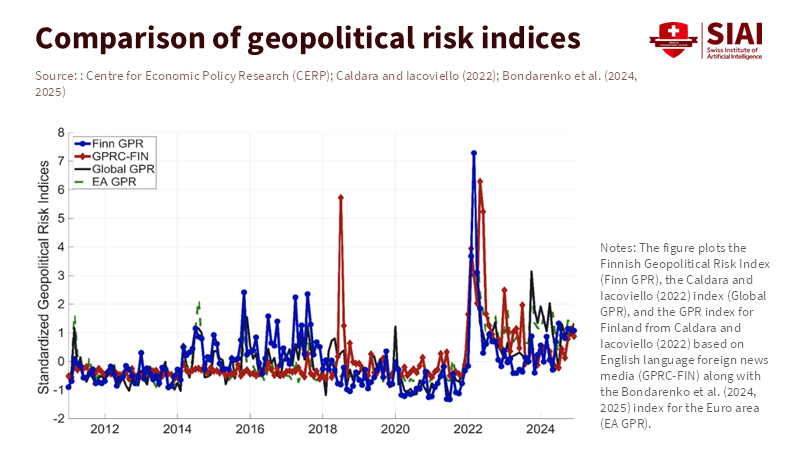

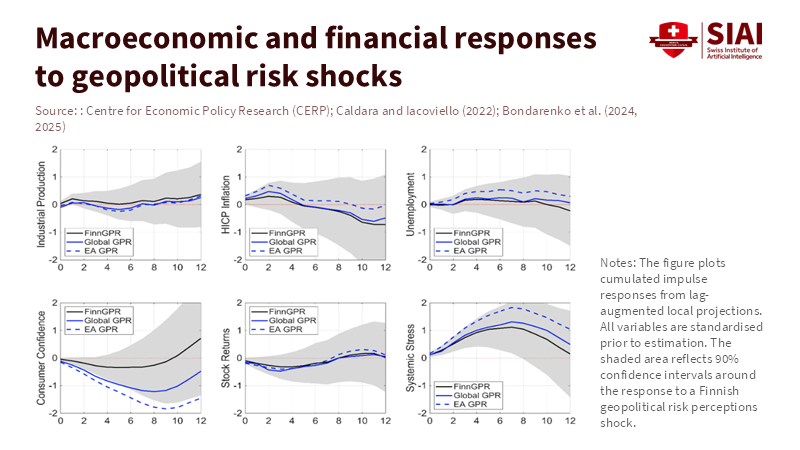

From this perspective, unmeasured risks often stem from data mismatches. This could be due to using the wrong language, communication channels, or level of detail, rather than to complete unknowability. The CEPR's effort to create a Finnish-language geopolitical risk indicator (FinnGPR) illustrates this well. Local reporting in Finnish revealed patterns of perceived risk that differ in timing and emphasis from those in Anglo-Saxon indices. This difference is significant because it shows that the domestic risk environment can seriously diverge from what the global English-language media emphasizes.

Local-language measures change the way we understand market prices. The price of a sovereign CDS or currency is like an umbrella, covering transactable risk, liquidity premiums, and the market's anticipation of future political or economic disturbances. If local news sources have already reported increased governmental pressure, supply-chain issues, or protest activity before English-language media, then a market that depends only on global feeds will react slowly. This delay results in mispricing and increased volatility. Studies on news-based geopolitical indices confirm that increases in these indices consistently coincide with noticeable shifts in asset prices. The most intense events, exceeding two standard deviations in country-level GPR indices, correlate with increases in CDS spreads and decreases in equity values. This suggests that more detailed, multilingual measurement can narrow the gap between a country's actual political economy and the price reflecting it.

Local news, geopolitical risk, and the incorporation of Large Language Models in Finance

Here is another way to think about technology: Large Language Models (LLMs) make it possible to extract information from local-language texts, but doing so is not the same as doing it well. Financial firms are now experimenting with custom finance LLMs and in-house LLM packages. Banks and data providers are using these for research, summarization, and sentiment extraction. Industry and regulatory surveys show that more of these tools are being used. The benefits are twofold. LLM pipelines that handle multiple languages can detect subtle, contextual clues in local reports. These clues, such as tone and conditional language (may versus will), that simple dictionary searches miss, affect how carefully people act. LLMs also enable dynamic translation and the linking of different entities, enabling comparisons of how the same geopolitical stress is portrayed across languages and sources. This exposes differences that are important for domestic policy and for cross-border effects.

This tech has its downsides: model bias, blind spots in training data, and poor governance. LLMs can exacerbate measurement errors if they are not tuned to the local media scene. European regulatory and research groups, as well as recent surveys on LLMs in finance, state that use must include adapting to the specific area, monitoring data sources, and stress-testing to verify results.

A link is forming between reading the news and market results. Recent university work shows that daily business news expects market swings, and turning that signal into something machines can read and trade on is now possible. However, turning attention into price requires two more steps: obtaining reliable information and linking it to a tradable risk premium. Seeing a local spike in risk words is one thing, but getting an asset manager to change sovereign exposure or increase credit hedges requires solid proof that the signal signals a realized loss or increased funding costs. This is where local-language indices, checked against rapidly changing market data, provide value.

What Institutions Should Do Moving Ahead in Policy, Pedagogy, and Practice

There is another way to think about it, which involves shifting from measurement to institutional change. If local news geopolitical risk is real and something can be done about it, then educators, regulators, and market players should build three things: data infrastructure in multiple languages, clear methods, and governance that links signals to economic action. For universities and training programs, this means teaching economists and risk managers how to design studies, use multilingual NLP, and validate findings. Classes should treat language as part of the data system: choose representative outlets, understand bias, and test whether changes in local reporting later explain funding costs. For regulators and central banks, the focus should be on receiving data. Regulators should ask that stress tests and market monitoring include a local-language media feed. This suggestion is reasonable, as it does not replace market prices but provides early warning and is helpful for smaller economies with limited global coverage. For those managing assets, the request is procedural: make sure any news-driven signal affecting portfolio decisions is clearly documented, and test it across political events to see whether it signals losses or just attention. The aim is to decrease the gap between what markets can see and what people and firms really experience.

There will be some complaints. Some might argue that local media is unreliable and biased, while others will say LLMs make things up. These concerns are important and must be addressed by how we approach the method. Noise can be mitigated by combining public media, independent outlets, and social checks so that a single unreliable source does not significantly affect the data. Bias can be measured by comparing topics across different outlets, tracking editorial cycles, and testing on non-political events. Model hallucination can be addressed by ensuring models cite their sources and by involving humans in important trade-offs. When done right, local-language measures reduce ambiguity by providing a clear path from text to score to policy.

When markets price what is not measured, the prices show a compressed, unclear view of many things. Building local news geopolitical risk measures is a policy move that decreases the gap between what those who live with political risk experience and those who have to price it. Large Language Models make the technical path possible, but that is not an excuse to use them blindly. The better choice is to be careful by creating multilingual collections from various sources, confirming signals against quickly changing market data, and locking models into frameworks that demand transparency and testing. Teachers must teach the tools; regulators must ensure transparency in their ingestion; and asset managers must document how they use text to drive trades. Doing this will allow prices to reflect the risks that matter to people in the area, not just the risks that global headlines choose to cover.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ambrocio, G., Fungáčová, Z., Heikkinen, J., Kerola, E., Korhonen, I., & Norring, A. (2026). Northern insights: Measuring geopolitical risk through Finnish news media. CEPR VoxEU column.

Aquilina, M., et al. (2025). Harnessing artificial intelligence for monitoring financial stability. Bank for International Settlements, Working Paper.

Caldara, D., & Iacoviello, M. (2022). Measuring Geopolitical Risk. American Economic Review, 112(4), 1194–1225.

European Securities and Markets Authority. (2025). Leveraging Large Language Models in Finance: Workshop summary and considerations. ESMA/ILB Turing Report.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 2: Geopolitical Risks—Implications for Asset Prices and Financial Stability. IMF.

Jiaxin Pei, Soumya Vadlamannati, Liang-Kang Huang, Daniel Preoţiuc-Pietro, Xinyu Hua. (2025). Modeling and Detecting Company Risks from News. arXiv preprint.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. reporting and industry announcements (2024–2025) on internal LLM deployments (LLM Suite and related tools).

University of Auckland. (2025). Can reading the news make you richer? Business School research briefing (30 June 2025).

Comment