Raw Ground, Finished Power: Why Africa Will Not Break China’s Rare Earths Grip

Input

Modified

China’s power in rare earths comes from refining, not mining African supply backed by Australia and India will not shift leverage without downstream processing and skills Without investment in finishing capacity, diversification will deepen existing dependence

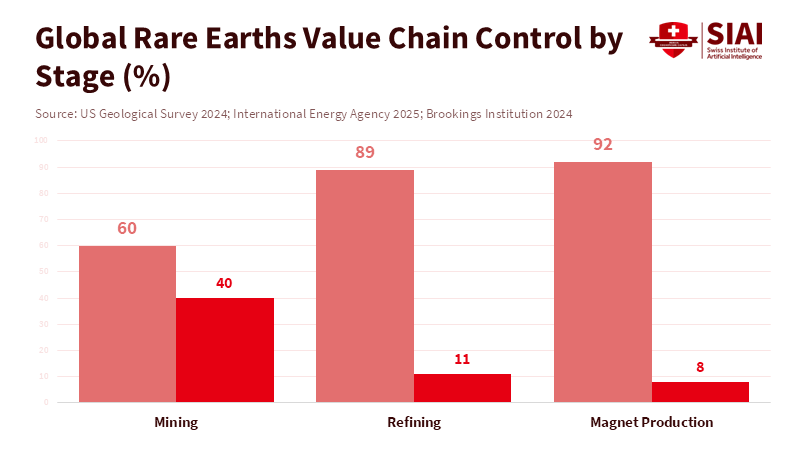

One number defines the modern rare earths supply chain more clearly than any diplomatic pledge or mining announcement: China processes close to ninety percent of the world’s rare earth elements into usable industrial materials. This dominance does not stem from exclusive control of mineral deposits. It stems from control over refining, separation, alloying, and magnet production—the stages where chemical expertise, industrial scale, and institutional patience converge. New mines in Africa, backed by Australian capital and Indian demand, are often framed as a turning point. Yet history suggests otherwise. Extracting ore changes geography, not power. Power shifts only when countries can finish what they extract. Without refining capacity, African rare earths will travel familiar routes to existing processors, reinforcing the very dependence diversification efforts seek to escape. The real challenge, then, is not where rare earths are found, but where they are transformed. Until policy confronts that reality, the structure of the rare earths supply chain will remain largely intact.

Africa’s geological promise and the limits of extraction

Africa has a lot of valuable minerals, but this potential is often overlooked. Exploration in southern and eastern Africa has found deposits with important amounts of neodymium, praseodymium, and other rare earths needed for high-performance magnets. These finds attract investment because some African ores contain several in-demand elements. Mining can bring export income, jobs, and better infrastructure, but just extracting minerals does not lead to real economic independence. More chemical processing is needed. Without investment in processing and strong institutions, African countries may remain as raw-material exporters while bearing most of the environmental and social costs. This situation affects geopolitics: countries with these resources could become strategic partners, not just suppliers, but only if they add more steps of the value chain. Policymakers need to weigh short-term profits against long-term investments in processing and good governance to safely manage complex chemical industries.

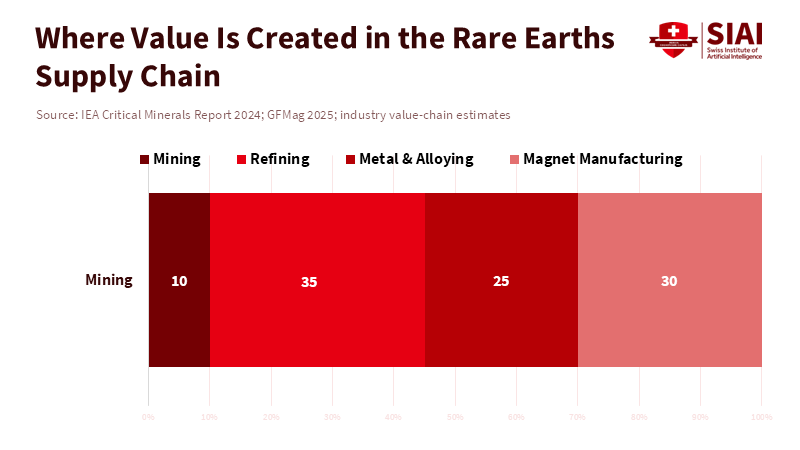

The rare earths supply chain and where value accrues

The rare earths supply chain is an extended sequence of specialised activities that accumulate value at successive stages. Mining yields ore; concentration produces mixed oxides; hydrometallurgical separation isolates individual elements. The rare earths supply chain comprises several specialized steps, each adding value. Mining extracts the ore, concentration turns it into mixed oxides, chemical separation isolates each element, metallurgical processes produce metals and alloys, and finally, magnets are manufactured from those metals. Each stage needs different equipment, skills, and rules. Mining is usually straightforward, but chemical separation and control are harder and less common. Most of the profit and control come from finishing the materials, not just extracting them. Because each step depends on the others, a problem in one stage can affect the entire chain. If there isn’t enough separation capacity, mines can’t get full value. If metallurgical capacity is lacking, magnet makers can’t get what they need. This means that diversifying supply is about designing the whole system, not just mining more. Composition, temperature control, and reagent quality. Refineries must also cope with waste streams that include low-level radioactive material, which require robust treatment and secure storage. These realities make refining capital-intensive and operationally demanding. Historically, China accepted these burdens, allowing firms to experiment, scale, and iterate on process improvements. Over time, this produced dense industrial clusters where chemical firms, equipment suppliers, and research institutes co-located. That clustering lowered costs and accelerated learning, creating a cumulative advantage that is difficult to replicate quickly. New refineries in other regions typically face higher initial costs, longer learning curves, and increased political risk because they must demonstrate environmental performance in contexts that may lack deeply experienced regulators.

Hands-on experience is key to refinery success. Chemists and plant operators learn to spot small changes in processes, understand how different ores behave, and solve practical problems. This kind of expertise builds up over the years and as people move between different plants. Formal education is important, but it is not enough on its own. Classroom learning needs to be combined with on-site training, job rotations, and mentoring. Building this kind of skilled workforce takes steady investment in vocational education, partnerships between industry and universities, and incentives to keep workers. Good ways to do this include scholarships that require local work, industry-funded training centers, and staff exchange programs. These steps help transfer skills and lower risks in new plants.

Australia and India: complementary assets and clear limits

Australia and India each offer important strengths for diversifying supply, but neither can quickly replace the current refining leaders. Australia brings funding for exploration, experience in delivering projects, and a strong record of meeting international environmental standards. Its financial markets and mining services help reduce risks in early development. India brings strong demand, especially from electric vehicle makers, wind turbine producers, and the defense sector, all of which need reliable supplies of magnets and high-performance alloys. When Australian investment, Indian demand, and African resources are combined, they can support projects beyond mining. Still, having the right intentions is not the same as having the needed abilities. Australia’s strengths are mostly in early stages, while India needs to rebuild supplier networks, chemical manufacturing, and engineering skills to support full finishing. Real cooperation will need shared ownership, technology transfer, and steady investment in local skills.

Staged industrial strategies that can work

A good industrial strategy should be implemented in stages and be based on results. The first step is to build separation plants that can reliably make high-purity oxides for key elements. These plants need to demonstrate they can meet quality and environmental standards before receiving additional funding. The next step is to expand metallurgical plants to turn oxides into metals and alloys for magnets. The third step is to support magnet manufacturing and assembly, ideally near where demand and skilled workers are. Each stage should have clear goals and agreements that require technology transfer and local training. Government buying commitments can give the steady demand needed for financial success. Clear milestones, open reporting, and independent audits help build trust and attract investors.

Financing finishing capacity needs long-term tools that also handle environmental risks. Blended finance, which combines public and private money, lowers costs and improves returns for refiners. Government guarantees and some public ownership can reduce early risks. Development banks and climate funds can help, while making sure environmental and social rules are followed. Procurement is also important. Governments and state companies can buy locally finished materials at a slightly higher price during the transition, giving a steady income. Laws should require technology transfer, joint research funding, local hiring, and money for cleanup. Performance bonds and independent checks help lower risks for investors and protect communities.

Environmental governance, social licence and human capital

Strong environmental management is key to any successful finishing strategy. Refining creates corrosive waste and byproducts that must be treated to meet international standards. Projects should set aside money for waste treatment from the start, create long-term stewardship funds, and use ongoing monitoring with public data. Independent audits and community monitoring make things more transparent. Community programs such as local hiring, supplier development, healthcare, and education help build support and reduce the risk of conflict. Making environmental and social safeguards a core part of the plan increases political stability and reduces the risk of costly problems that harm both communities and investors.

Building education and strong institutions takes time, but the rewards increase over the years. Universities should align their research with industry needs and set up joint research centers focused on process chemistry and corrosion control. Vocational centers should teach practical plant skills and offer apprenticeships that let students work in different parts of a plant. To keep skilled workers, there should be clear career paths, good pay, and fellowships that link academics and industry. Regulators also need training. Good environmental oversight depends on trained inspectors, labs to test emissions, and courts that can handle disputes. Donors and development banks can help by providing targeted grants and technical support.

Recycling, substitution, and complementary policies

Recycling and using substitute materials are helpful additions to building finishing capacity, but they can’t replace it right away. Recovering rare earths from old magnets, electronics, and car parts can provide an additional supply and reduce environmental impact, but recycling rates remain low, and the technology needs to be scaled up and standardized. Research into alternatives for the most limited elements is important and should continue, but many of the top magnets still require certain rare earths. A good policy should support recycling and substitution while also investing in new finishing capacity, making the supply chain more reliable and resilient.

It’s true that building finishing capacity is costly, politically sensitive, and takes time. It will mean higher short-term costs for consumers, and new plants will have a lot to learn. These are real concerns and should shape how projects are planned: they need to be done in stages, be open, and closely watched. Sharing costs and working with international partners can help spread the burden. The other option is to keep facing supply shocks and pressure from those who control refining. If seen as a form of strategic insurance, the higher costs now can pay off by giving more choices and reducing risks in the future. The best approach is to balance short-term costs with long-term strength.

New rare earth mines in Africa are a major global development. They increase supply, create jobs, and bring revenue to host countries. But mining alone does not change who controls the materials that power modern industry. The rare earths supply chain gives most of the power to the finishing stages, like refining, metallurgical conversion, and magnet making. If policymakers want real resilience, they need to go beyond just getting ore and focus on building finishing capacity that is environmentally sound, well-supported, and staffed by trained professionals. Australia and India can help drive these efforts, but only if they commit to joint ownership, long-term funding, strong environmental rules, and steady investment in people. Governments face a clear choice: accept surface-level diversification that keeps them dependent, or invest patiently and with purpose to shift the balance of power.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. Could Africa replace China as the world’s source of rare earth elements?

GFMag. China’s grip on rare earth elements.

International Energy Agency. Critical Minerals and Supply Chains.

TCADI. Rare earth minerals in Africa: Strategic outlook.

US Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries: Rare Earths.

Comment